Early advertisements 1904–1905.

Early advertisements 1904–1905.

Early advertisements 1904–1905.

The “ideal home”, 1923.

Industrial modernity, 1925.

Endorsement advertising, 1985.

A correlation of interest between journal and advertiser promoting the flat roof, 1908.

The builder on the job, “beefy” and “sun-tanned”, 1975.

The figure of the architect as “rational designer”, 1962; “reflective and thoughtful”

The figure of the architect as “rational designer” 1994; nearly always male.

Depictions of women: causing controversy in 1982.

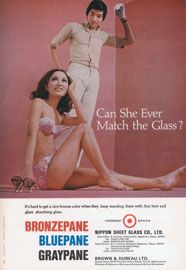

Depictions of women: bikini clad in 1970.

The centenary celebrations of Architecture Australia should not pass without recognition of the longstanding association building product advertising has had with the journal. Back in 1904 the first issue of the Journal of the Institute of Architects of New South Wales carried advertisements for Lysaght’s Galvanized Iron, Royal Doulton Potteries, The Commonwealth Portland Cement Company and the Welbach Incandescent Light System, among others. Since then, building product advertising has maintained a continuous presence in the journal, riding the changing fortunes of the building industry through times of depression, war and economic prosperity. Indeed, on the advertising pages of the journal it is possible to chart a history of the material (and mythical) production of modern architecture in this country: the promotion of electric lighting for the home, the development of reinforced concrete, the introduction of whitewash, the marketing of aluminium, and the appearance of Laminex, to name a few highlights. The importance of advertising to the journal has never been lost on its editors, as advertising has constituted the principal source of revenue for the journal’s production and development. For this reason the journal has had to remain attractive to its advertisers, with editors framing this relationship as one of “mutual advantage”. Building product manufacturers receive a high level of exposure to a large portion of the architectural profession, while the journal enjoys the revenue generated through advertising contracts.

The study of building product advertising might start by looking into the great manufacturing companies that have risen within the building industry in Australia and how these companies have marketed themselves and their products to the architectural profession. Some of the larger manufacturers include Wunderlich Limited, Berger’s, CSR, John Lysaght Limited, ACI Australia Limited, Hardies Industries and BHP, all of whom have been regular and prominent advertisers within Architecture Australia and its predecessors. These companies have set up their own sales departments and have hired advertising agencies to design and administer advertising campaigns for them.

The aim of these campaigns has been to establish awareness about a particular product within the building industry and to impress upon architects why it should be specified.

To assist this exercise in persuasive communication advertisers have deployed symbolic codes and references to enhance the image of a product and to dramatize its use and potential value. It is worth considering what these codes have been over the past one hundred years of the journal’s publication.

In the early issues advertisements mainly took the form of company “announcements”. These were based on an informational approach, with text providing “rationalistic” reasons for using a given product or supplier. By 1910 artistic renderings had become common, often illustrating a house and its garden setting. These renderings exploited notions of the “home beautiful” and “the ideal home” that were current within architectural discussions at the time. In the 1920s advertising entered a new phase of production. Less emphasis was placed on explanatory text as advertising started to construct symbolic associations for product promotion. Images came to dominate the space of advertising, encoding materials and products in the language of industrial modernity. Photographs of city skylines, factories and symbols of mass production were used to link materials and products with the themes of utility and progress.

The postwar era saw a proliferation of building product advertising, and advertisers deployed a greater range of strategies. One of these strategies was to use the figure of the architect in the advertised image. This was done in order to draw the architectviewer into a closer relationship with the product. Here we see the strong gender bias that has informed building product advertising, for the figure of the architect has almost always been cast as male. Throughout the 1950s and 1960s the architect was pictured as a middle-aged man, a “rational” designer, with a clear head for business. By the 1990s the figure of the architect had become younger, more introverted and reflective.

The architect has usually been pictured explaining a drawing in the context of a harmonious exchange between himself and his clients, who have always been depicted as the willing and passive subjects of the architect’s authoritative gestures and gaze.

This image has been used to promote a wide range of different products and technologies from insulation to escalators. It conveys a concept of authority that advertisers use to bridge the gap between a successful business scenario and the specification of a given item. Making the ideal look real is a central part of how advertisements work to mythologize the act and space of architectural design.

As with advertisements more broadly, the representation of the female body in building product advertising has nearly always been an exercise in objectification.

Whereas men have mostly been shown occupying sites of creative and physical production, women have traditionally been portrayed in domestic and secretarial roles, if they are not sitting or lying around in their bikinis (as they were in the early 1970s).

Advertisements have equated feminine beauty with the beauty of building products and furnishings. In the 1960s, building product advertising constructed feminine beauty in terms of softness, naturalness and submissiveness. In contrast, the 1980s female was represented through images of independence and self-assuredness, being aligned with products hyped for their versatility and practicality. One of the most shocking examples of sexism in the journal’s advertising appeared in 1982. It showed an elegantly dressed woman tied to a chair with her mouth gagged. The advertisement was for a brand of noise control products and had a caption reading, “We have ways of keeping you quiet.” Readers responded with an outcry and the advertisement was withdrawn.

Advertisers have also composed images around the social, intellectual and physical distinctions that stereotypically separate architects and builders. On the one hand, builders are beefy, sun-tanned and semiliterate men who, while waiting for materials to arrive or the rain to stop, spend their time reading newspapers, lazing around or playing cards. Architects, on the other hand, are stylish, well-groomed and educated men engaged with their work. When not at the drawing board or in a client meeting, they have often been shown stepping through doorways – a metaphor that could be interpreted as representing movement, social mobility and career advancement.

In his 1992 book, Reading Ads Socially, Robert Goldman points to the growing scepticism advertisers faced from consumers in the early 1980s, describing a crisis in believability over the idea that one’s happiness could be achieved via the consumption of commodity aesthetics. To accommodate changing consumer attitudes, advertisers had to deploy new tactics of symbolic persuasion. Endorsement advertising was one such tactic, in which the name and face of identifiable personalities were used to lend credibility to a product. In the mid-1980s, endorsement advertising was a feature in Architecture Australia. A good example is a 1985 advertisement for BHP Steel in which Philip Cox stands in front of the shade structures of the Yulara Tourist Resort at Uluru. The architect’s face projects an image of quiet professional confidence, with the name of the steel maker inserted into the advertisement’s circuitry for signifying architectural achievement.

Given the dependence the journal has on building product advertising, the question of whether correlations exist between editorial interests and the promotional interests of advertisers needs to be asked. For the producers of The Salon, which ran from 1912 to 1917, it was desirable that advertising shared a similar texture to its other contents.

They stated, “The aim of The Salon is to have the advertising pages not only as interesting, but equally as informative in their province, as the others. It seeks the cooperation of advertisers to that end; it offers them its own co-operation for the same purpose.” Indeed, there have been several episodes in the history of the journal that testify to this correlation of interests. For example, during the late 1900s the editors of Art and Architecturewere engaged in a campaign to introduce the idea of flat roofs to the Sydney architectural profession. They argued that the climate in Australia necessitated outdoor living and that architects should embrace the concept of the flat roof when designing their buildings, especially houses. The problem, however, was that flat roofs needed special waterproofing treatment. Two of the journal’s main advertisers at this time were The Paraffine Paint Company, the makers of Malthoid, and the Australian distributors of the American product, Ruberoid. Both companies had been advertising their range of watertight bituminous substances in the journal for a number of years. As the argument about flat roofs gained momentum the manufacturers of Malthoid and Ruberoid started promoting their products in terms of flat roof buildings.

In tune with this move, editorial commentaries and journal articles began to make explicit and favourable references to these products and their manufacturers. There were also other instances of editorial and advertising crossovers at this time. In later years the publishers of the journal created separate sections for product publicity, in which the distinctions between advertising and editorial matter were more clearly marked. An interesting study could be done of this relationship and the different discursive and promotional modes through which building products have gained visibility and appeal.

When contemplating the pros and cons of building product advertising in 1913, a writer for the journal (who remained nameless, but who presumably was an architect of some critical sensibility), pondered whether advertising had a productive role to play in the creative life of the architect. Discarding “publicity cards” as negligible, the writer favoured “educational advertisements” – advertisements that were devoted “entirely to instruction concerning an article manufactured or stocked by the advertiser”, but which also functioned to “boost” a product. When assessing the effectiveness of this advertising – which was only ever educational if it reached architects through the proper channels – the writer offered this insightful commentary, and one by which I shall end this appraisal:

“All educational advertisements are a benefit to the reader. Advertisements in this class are worded strongly and as strikingly as the truth will permit, and for this reason they are impressive and may start new ideas and chains of thought in the mind of the reader. To-day, the selector may not need a certain article, but within a year such a thing might be wanted; his mind, then, at once reverts back to the advertisements he has read. Possibly, the name of the manufacturer is impressed on his memory. Such things have actually happened not once, but many times. The medium by which the goods are impressed on the selector’s mind, and eventually bought, may never directly or indirectly come to the ear of the seller; yet the seller will find by stopping his advertisements in a channel which comes directly in contact with the selector, his sales become less and less. Often an advertisement is meant for one purpose, yet it will start a chain of thought in the architect’s mind that will lead him to thinking, so that he will originate new ideas, new designs that will be a benefit both to himself, his client, and the advertiser.”

Paul Hogben is an association lecturer within the architecture program at the University of New South Wales.