In Australian architecture, the word Troppo has a very specific meaning: an architectural practice that has, over more than thirty years, without swagger or pretension, investigated questions of climate, history, construction practice and place. The result has been a distinguished series of award-winning buildings, an international reputation, offices across five states and a permanent place in Australian architectural history as a practice determined to find and promote – through its focus on environment – a valid and enduring design aesthetic. And it all started in Darwin in Australia’s Top End. Unlikely? Perhaps, but not really if one considers the circumstances: the devastation wrought by Cyclone Tracy in December 1974 that urged Darwin’s rebuilding coincided with a moment in the mid-1970s when unresolved questions of history, building type, environment and social responsibility had the entire Australian profession on edge. If there were Australian practices intrinsic to the global revival of the term regionalism in the 1980s and an emergent confidence in our ability to describe multiple identities for Australian architecture, then Troppo counts among the most important. The firm’s founders might be embarrassed by this accolade. But it’s the truth: what started in jest has now become lore.

Phil Harris and Adrian Welke, co-founders of Troppo Architects.

Image: David Sievers

Phil Harris and Adrian Welke established Troppo in Darwin in 1980. Historically, the phrase “going troppo” meant to be heat-affected – one “went off,” a little mad in the heat of the tropics. But for Welke and Harris, going troppo meant becoming acclimatized, not going off at all but understanding the place. Their tongue-in-cheek name for their firm lived on. Welke and Harris both graduated from the University of Adelaide in 1978. A student road trip in 1977–78 by Welke, Harris, James Hayter and Justin Hill in a Volkswagen Kombi, clockwise around the coast from Adelaide to Perth, Broome, Darwin, Normanton, Cairns and Sydney, revealed an untapped resource of regionally appropriate architecture. They were especially taken with the historical architecture of the Australian tropics. By 1979 Welke had moved to Darwin, working first for government and then for Vin Keneally and Associates, and Harris joined him there that year. From 1980 on, the pair developed a unique, regionally specific architectural enterprise in the Top End of Australia: essentially the northern third of the Northern Territory, the part of Australia closest to Indonesia, closer to the equator than Bangkok, and with a demanding tropical climate and distinctive wet and dry seasons.

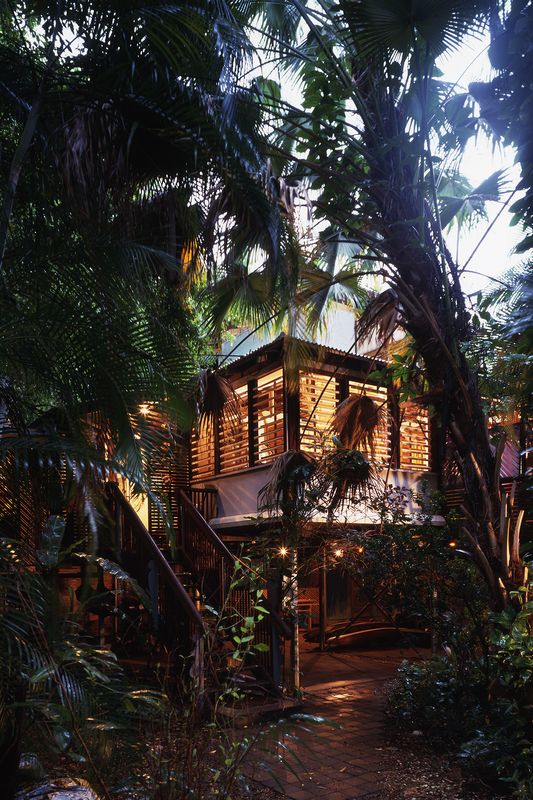

The love tents, Anbinik Kakadu Resort (formerly Lakeview Park), Jabiru, Kakadu National Park, NT, 1995.

Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

Harris and Welke formulated a series of thematic constants or design guidelines, each a direct response to the environment, building technique and social behaviour. An early indication of these was self-published as Punkahs and Pith Helmets: Good Principles of Tropical House Design (1982). The idea of the adjustable building skin was crucial. The firm’s studies of Top End building heritage revealed the benefits of a building skin, which might be easily opened, closed and adjusted according to the season. The examples of Beni Burnett’s 1930s louvred houses, the battens and folding shutters of early-twentieth-century slatted houses, roll-down blinds and the laminating of roof eaves like the canopy of a tree all offered lessons. A significant early project was the low-cost house prototype built in Karama, NT (1982) and nicknamed the “Green Can” after the signature green Victorian Bitter beer can.

Troppo House under reconstruction, Coconut Grove, Darwin, NT, 1981.

Image: Courtesy Troppo Architects

Designed around a ventilating breezeway and a roofed outdoor room in the centre of the house, this project was the first in a long series of climatically adjustable houses. Another prototype house, the Tropical House (1990), explored the high-set house with a tall hip roof, a ventilator at its peak and diagonally located banks of louvres to encourage cross-ventilation. Placing corridors outside, using rammed earth walls for cooling mass, using decking inside houses, locating openings that afford cross-ventilation, employing the open frame and potentially unenclosed volumes, and exploring the idea of extendible and infinitely adjustable space are trademark Troppo elements.

Troppo also acknowledges the necessity of imported or transported materials in a place that cannot provide enough natural building materials. The use of corrugated iron, steel framing, plywood timber panels, fibro cement sheet and louvres, and the concept of building as a kit of parts, freely assembled and disassembled, inform its work and are exemplified by more than fifty projects in Darwin and surrounding areas, including the restaurant Pee Wee’s at the Point (1998), by housing at Kakadu National Park (1998–2001) and by the dynamic Rozak House at Lake Bennett (2001). Other Troppo constants include “hearing the rain” (using architectural elements to enjoy the thundering of rain in the wet), “inside–outside” houses, and using parasol roofs and deep overhangs, large enough to provide outdoor living space in the wet. Another is allowing houses to grow organically with need, especially relevant to Troppo’s extensive work with Aboriginal communities such as the Tjilpiku Pampaku Ngura aged-care facility in Pukatja, SA (2000) for the Nganampa Health Council. In those projects, Troppo uses the work of Healthabitat and Paul Pholeros, especially Housing for Health, which the firm has applied across numerous projects in remote locations in the Northern Territory, South Australia and Western Australia.

Bowali Visitors Information Centre in association with Glenn Murcutt, Kakadu National Park, NT, 1992–94.

Image: John Gollings

In 1987 Troppo designed park structures, entry stations and ranger housing at Kakadu National Park, 250 kilometres east of Darwin, the beginning of more than ten years of work at one of Australia’s most culturally significant sites. Harris and Welke invited Glenn Murcutt to work with them on designing the Bowali Visitors Information Centre at Kakadu (1992–94), a project that involved close collaboration with Kakadu’s Indigenous traditional owners.

In 1993, Troppo opened an office in Townsville. Harris returned to Adelaide in 1999 to open a branch office and, in 2000, the Perth office opened. From the mid-1990s, the Troppo message moved beyond the Northern Territory as projects, mainly housing, were undertaken on Kangaroo Island and at Coffin Bay, SA, for example, at Esperance, WA and, importantly, in Townsville, Queensland – the Lavarack Barracks (1999–2001). With Bligh Voller Nield, Troppo completed a masterplan and design of 1100 dwelling units and associated mess facilities to create one of Australia’s largest army bases, proof that Troppo ideas could be applied to large-scale projects. By 2010, Troppo had offices in Darwin, Perth, Adelaide, Townsville and Byron Bay, with buildings scattered across the nation as well as in Malaysia, Israel and Bali. One of the firm’s most unusual projects, far from its usual place of practice, was in the Australian Antarctic Territory, when Adrian Welke joined an eight-person team to conserve and restore prefabricated timber Mawson’s Huts at Cape Denison.

Ironically, I became properly aware of Troppo through overseas visitors, not Australians. Italians Paolo Tombesi (now at the University of Melbourne) and Riccardo Vannucci, then visiting in 1986, urged me to write with them an article (later published in Spazio e Società) about corrugated iron and to include work by Troppo. They had visited the firm. I had not. In the lead-up to Australia’s bicentennial in 1988, Troppo’s work forced me to broaden my horizon beyond Melbourne’s myopic but intense architecture culture. But it was photographer Patrick Bingham-Hall’s invitation in 1998 to write a book on Troppo that sealed my interest. As Patrick tirelessly photographed its buildings in searing temperatures and humidity, I would wander (mostly dazed by the heat) among Troppo’s houses, grateful for their shade. I finally came to understand Troppo’s closeness to place, and also the design necessity, at times, of being able to build with stuff just from the back of a ute – the realities of construction practice in remote Australia. Meeting Phil and Adrian – welcoming, relaxed and unassuming – also confirmed the myth: Troppo was real. Patrick’s books, Troppo: Architecture for the Top End (1999) and its second edition in 2005, were fitting tributes to the firm’s unique practice and I feel extremely privileged to have been involved in that venture. Only now does it seem to have been part of something much bigger.

Over the past thirty years, architecture in northern Australia has undergone something of a renaissance. The list of architects from that part of the continent who receive worldwide attention continues to grow. Troppo can be grouped with other Australian Institute of Architects Gold Medallists Glenn Murcutt, Gabriel Poole, Brit Andresen, Kerry Hill, and Lindsay and Kerry Clare. Common to all is the leading role that climate plays in determining the forms of their architecture. It is a different preoccupation from that of many architects in southern Australia, whose tense manipulations of form and symbolism occupy an altogether foreign architectural position to their northern counterparts. That can only be good for architecture in this country.

When outsiders view Australian architecture, preconceptions abound. Invariably, the image of a romantic primitivism, of a dreamy tent or shed-like house set within an idyllic antipodean Arcadia, is proposed. Troppo’s architecture can be seen in this light – for a fleeting moment. But there is something tougher in Harris and Welke’s contribution, also something a little looser and a bit more flexible. It has to do with their location, the heat, the people and the type of work they do. This is not an excuse but an advantage. It is as if their architecture at times relates to the archipelago lying north of the Arafura Sea, and at others to the outback tradition of the rural tin shed, and to the fluid growth of Indigenous shelter, a non-constant architecture. It is an open system, indicative of the history of nomadism of the place (both Indigenous and non-Indigenous). But it could also be suggestive of an impending permanence. Troppo, to its founders’ surprise, has become established. The name is now an institution.

Even with the diversification of Troppo’s activities throughout Australia and overseas, with projects in every Australian state, it is clear that no end to the firm’s experiments is in sight. What began as an idea among friends has grown into a multi-practice entity that includes expertise in urban design. In expansion, the risk was that Troppo’s diaspora might weaken its creative base. This hasn’t happened. Harris (now based in Adelaide) and Welke (now based in Perth) continue to fly across the country; they meet up in dusty outback townships or in the heady buzz of state capital cities. Troppo’s fundamental mission hasn’t changed. A critical engagement with place, climate and culture, and with how architecture might interact with and inform those issues, has provided ongoing sustenance for an increasingly relevant group practice, where energy saving, the ethics of climate and a sensitivity to landscape demand responsibility. In this, Phil Harris and Adrian Welke continue to be insatiable – it seems they are always entering another phase of “going off,” of “going Troppo.”

Read the 2014 Gold Medal jury citation from the special edition of Architecture Australia.

Further Reading

Jennifer Taylor, Australian Architecture Since 1960 (Sydney: Law Book Company, 1986).

John Archer, Building a Nation: a History of the Australian House (Sydney: Collins, 1987).

Davina Jackson and Chris Johnson, Australian Architecture Now (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000).

Philip Goad and Patrick Bingham-Hall, New Directions in Australian Architecture (Balmain: Pesaro Publishing, 2001).

David Bridgman, Acclimatisation: Architecture at the Top End of Australia (Red Hill: RAIA, 2003).

Adam Mornement and Simon Holloway, Corrugated Iron: Building on the Frontier (London: Frances Lincoln, 2007).

Philip Harris and Adrian Welke, Punkahs and Pith Helmets: Good Principles of Tropical House Design (Darwin: Troppo Architects, 1982).

Philip Goad, Paolo Tombesi and Riccardo Vannucci, “Poetry in Iron,” Spazio e Società, 43, July/September 1988.

Philip Goad and Patrick Bingham-Hall, Troppo: Architecture for the Top End (Balmain: Pesaro Publishing, 1999, second edition 2005).

Source

People

Published online: 20 Mar 2014

Words:

Philip Goad

Images:

Courtesy Troppo Architects,

David Sievers,

John Gollings,

Patrick Bingham-Hall,

Paul Pholeros,

Peter Eve

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2014