In the Pines, 2008. Commissioned by TarraWarra Museum of Art, 2008. Courtesy of the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne.

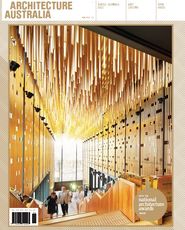

Image: John Gollings

Pulling up in the car park at Heide, the estate established by John and Sunday Reed and haunted by Melbourne art-world mythos, a Le Pine Funeral Services sign registers through the bushy landscape, somehow at home amid signs to galleries and a swanky cafe. The funeral home sign, however, is a folly; entitled In the Pines (2008), it is a Venturi-esque nod to the play between monument and sign, setting the scene and marking the entry to Callum Morton’s In Memoriam, an absorbing retrospective of the artist’s twenty-year oeuvre.

The longstanding duel between the legibility of architecture and its effacement by the sign is emblematic of the modernist project. It figures in Morton’s work from his earliest drawings and prints, later taking form in a range of models at varying scales; this is the work for which he is most renowned.

The drawings, rarely seen, are facade studies of public housing tenements, whose felling across the world signals modernism’s demise. Morton attempts to breathe life into the type via surface treatment, the application of colour and pattern glossing over the facade, testing it variously to read as landscape – see Garden City (1992), sign Untitled (1992) and Camouflage (1992) – though the problem of public housing remains and is anything but superficial.

Writ large in his ongoing series Canopies (1995–2011) is the double entendre of “the strip,” all show and no substance, commercialized and linear. Presented as a foreshortened streetscape, it reads forebodingly of Swanston Street denuded of its civic buildings. The awnings with their colourful logos read clearly and resonantly, despite the lack of any other architectural feature, reflecting how shopping is increasingly touted and institutionalized as our raison d’être.

One to One, 2011. Courtesy of the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne.

Image: John Brash

On a more intimate and parochially gothic note, a new work, One to One (2011), is a site-referential re-creation of a McGlashan Everist fireplace located in Heide II (1963), in which we eavesdrop on a conversation between the departed Reeds, who speak of dogs and suicides. This project exists as a legacy of earlier and other iconic models, though at a diminished scale in which architecture itself is the site of tragedy, such as International Style (1999), a model of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House (1951), curtained, with a party happening until a gunshot sounds; Gas and Fuel (2002), a replica of Perrott Lyon Timlock and Kesa’s Gas and Fuel Corporation Towers (1967), which were flattened to make way for Federation Square, plaintive cries of “help me, help me!” echoing, the towers personified as helpless and cognizant of their demise; and Open House (2006–2011), a remaking of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye (1929), which projects its own internment, ironic and Lazarus-like, as it was once a ruin, having since been restored and reclaimed.

Monument #26: Settlement, 2010. Courtesy of the artist and Anna Schwartz Gallery, Melbourne.

Image: John Brash

More recent, though less concerned with architectural icons per se, is Morton’s Monuments series. These works are particularly rich and enigmatic, calling to mind Adolf Loos’s claim that “only a very small part of architecture belongs to art: the tomb and the monument.”

Monument #26: Settlement (2010) is coffin-like in both proportion and scale and almost Mitford-esque in its matter-of-factness and demeanour. (Jessica Mitford, one of the famous Mitford clan, railed against the mercenary nature of the funeral industry in the US during the 1960s and, in her perhaps dubious honour, had a plain pine casket named after her.) The work presents as a large, misshapen cardboard box seemingly held together with packaging tape and with a blue tarp tied over and lidding it. Like a tomb, it conceivably contains trappings of the afterlife within, accoutrements necessary for setting up house – establishing a “life” – elsewhere. Suggestive of our increasingly nomadic existence and sense of placelessness, it also implies that culture is something that is ingrained and held within, moving with us, and which is only precariously and temporarily contained.

Monument #28: Vortex, 2011. Courtesy of the artist and Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney. Image:

John Brash

Votive candleholders in the shape of buildings form part of the merchandising, and in the wake of modernism’s passing, In Memoriam suggests that the melodrama has not yet played itself out, with seasons yet to be produced, rich for Morton’s and our own working through. In lamenting, it is not always so much that we simply remember but, perhaps more importantly, what we choose to carry forward. Herein lies the intrinsic value of In Memoriam and the surveying of Morton’s oeuvre.

In Memoriam was on display at Heide from 16 July to 16 October 2011.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 1 Nov 2011

Words:

Peta Carlin

Images:

John Brash,

John Gollings

Issue

Architecture Australia, November 2011