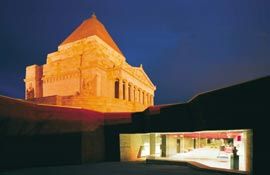

View from the new Entry Courtyard, with the Shrine seen above and the new exhibition and reception areas housed in the undercroft below. Image: John Gollings

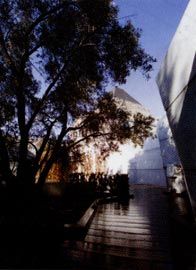

North elevation of the Shirine of Remembrance, with the new areas housed in the flanking walls. Image: John Gollings

View along the Wall of Medals in the entry arcade. Image: John Gollings

The Hall of Columns occupies an existing space beneath the Shrine opening up a new approach to the Crypt. Image: John Gollings

Hudson & Wardrop’s orginal design for the Shrine and its surrounds. Image: John Gollings

The new view of the Shrine from the Garden Court. Image: John Gollings

Overview of the garden by Rush\Wright. Image: Peter Clarke.

Places of repose and reflection within the Garden Court. Image: Peter Clarke.

Places of repose and reflection within the Garden Court. Image: Peter Clarke.

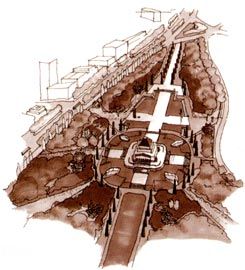

Rush\Wright’s masterplan for the Shrine Reserve.

The faceted red walls of the Entry Courtyard, with Lest We Forget inscribed across them. Image: John Gollings

View from the arcade across the courtyard to the entry. Image: John Gollings

With Ashton Raggatt McDougall’s addition to the Shrine of Remembrance in Melbourne and RushWright’s masterplan for the Shrine Reserve – an 11-hectare site incorporating the Shrine itself – two architectural concerns predominate.

The first involves the insertion of a new programme into a pre-existing building, one that already has both iconic and programmatic importance within Melbourne. The second is the differentiation of the Shrine Reserve within the Kings Domain, where this needs to occur as an effect of the landscape rather than through the insertion of simple boundaries. These concerns overlap at a number of important points and both relate to more general architectural problems.

War memorials in both Australia and New Zealand generally commemorate service in the armed forces rather than simply honouring those who died. In this context, memorials have a different sense of occasion. While functioning as important locations of memorialization, they also need to house more complex programmes. That is, the necessity of allowing for both for the memory of dead and the continuity of recognition for those who served, and who continue to serve, creates a different project. Moreover, the highly contested nature of war, the impossibility of simple glorification and yet the necessity for formal acknowledgment introduces a further set of constraints.

This is the context in which ARM’s Shrine of Remembrance project operates.

Responding to the need to create sites for administration, display and educational activity, the problems were always going to concern the visual quality of the addition and its effect on the existing structure. ARM have located most of the new programme beneath the Shrine, and this has a number of important consequences. The first is that the addition is visually registered by the geometry of the exterior walls that flank either side of the front. Their symmetry comes not from the plan but from their relation to the geometry of the original shrine. The use of entasis in the original Hudson & Wardrop building – completed in 1933 as the result of a public subscription – means that the symmetry of the original is created by angles of projection as much as by a simple relation between the horizontal and the vertical. The layering of the elements comprising the new exterior faceted wall has to be understood as a contemporary architectural response to this original form. The question is, of course, what makes it contemporary? Part of the answer is found in the way that contemporary design processes and materials are used, not to mime the original, but to pick up its organizing geometry and to reiterate the work of a geometry that has both an immediate effect and a projected one.

The question of symmetry is especially interesting in this context. Looking at the overall plan, the Entry Courtyard and the Garden Court are symmetrical in terms of location. The symmetry of the elevation, however, is given by the geometry of the initial building. This means that there is no need to define the symmetry of these elements internally. As a consequence, the Entry Courtyard and the Garden Court can take on individual qualities, while the overall order of the addition and its relation to the existing building is maintained.

The Shrine is now entered through the new courtyard, via a display area in which all the medals marking military activity are mounted on a wall running almost the entire length of the addition. Set into the ground of this arcade, beneath the wall, is a display of poppies (by Cunningham Martyn Design). While the new work is relatively straightforward in terms of its operation, two programmatic elements demand further consideration – the courtyard and garden, and the new connection to the Crypt. This connection is significant as it opens up the Shrine in a way that the original plan did not envision – but nor did it preclude it. The visitor now moves from the Wall of Medals arcade to the Crypt through the Hall of Columns, where the building’s original support columns are revealed. The height of the roof, combined with the effect of these columns, creates a space imbued with a certain sanctity, derived from both its position in relation to the Crypt and the way the Crypt illuminates it. The addition releases the potential of this existing space. Here is an instance where the architecture does the work.

The Entry Courtyard not only provides a new visual relationship with the Shrine – a state of affairs that is repeated in its own way in the Garden Court – the faceted walls also deal with the question of monumentality in original ways. While the organizational geometry discloses a space that is more than a simple forecourt, other elements are also of real significance. For example, the colour – perhaps recalling the colour of the original edition of C. E.W. Bean’s history of the First World War – raises interesting questions. It allows the broader problem of colour in architecture to be posed, but it also raises the question of what colour is appropriate to the process of memorialization, and, in part, resolves this. It is possible to suggest that there is partial resolution because of the inherently secular nature of the site. Rather than being religious in character, the Shrine concerns relations between community and memory. Colour is deployed to give this relation – a relation eschewing the religious – a more contemporary presentation. ARM’s use of colour, as with the use of hand writing as a contemporary plaque (the words “lest we forget” are written across the walls) can be understood as an attempt to give architectural resolution to these specific issues of memorialization. The red colour, in not having a determined point of reference, creates a site where meaning is not given in advance. This refusal of the symbol on the part of the architects marks an important departure.

The Garden Court has allowed landscape architects RushWright a place to work within the addition. The garden takes up the theme of creating a setting of reverence and a sense of sobriety, while articulating these within an architectural language that is inherently secular. The garden picks up the organizational lead given by the walls. A circulation path, yielding places of repose, establishes a place of reflection. The presence of an olive tree in the middle recalls the interplay of war and peace while resisting any immediate form of glorification. Sobriety is reinforced by the view of the Shrine afforded by the garden and this heightens the function of the garden as a site of reflection.

The development of the undercroft of the Shrine occurs in

the context of RushWright’s new masterplan for the Shrine Reserve. This plan envisages an area for the Shrine that will have a distinct location in the overall reserve. Boundaries will be established by a reworking of the contours, a tree removal and planting plan and the construction of a new grassland policy. If there is a guiding motif for the plan, it has to do with the problem of continuity and renewal as raised by this site.

One of the many elements that could be taken from Hudson & Wardrop’s commitment to a form of Classicism is the possibility of reusing the relationship between temple and site that had such an important effect on Greek architecture. As archaeological evidence bears out, the temple can never be divorced from the site.

What exists is a temenos (RushWright also use this term in the documentation). If this is the point of departure, how might this relationship between temple and site to be understood now? What is a modern temenos? While part of the answer involves shifts in the landscape, landscaping is also an architectural response to the creation of a site that, while having aspects of the sacred, is not counterposed to the profane. Indeed, such opposition is simply unacceptable to any modern sensibility. And yet, if the modern cannot allow for any sense of sanctuary, then a real site of memory – architectural acts of memorialization – would become impossible. The resolution here in terms of landscaping is to address the question of the differentiation of the Shrine Reserve, and its internal operation, in terms of access and movement. In general, the relationship between contours and movement will work to identify the site. That is, the area will be defined as a modern temenos by the movement onto the site across a threshold which will involve a shift the quality of public space. The modern temenos depends on the public nature of architecture – and thus the public as both modern and secular – and on a complex sense of the public and thus public space.

There is, therefore, a real affinity between the two projects. It is not just that they are intended to work together. Rather, they can both be understood as architectural responses to the question of how, today, is it possible to deal with the reality of war and service without falling into the trap created by “God and Country”.

Credits

- Project

- Shrine of Remembrance undercroft development

- Architect

- ARM Architecture

Australia

- Project Team

- Ian McDougall, Howard Raggatt, Steve Ashton, Ken Bool, Tim Wright, Andrew Lilleyman, Neil Masterton, Daniella Casamento, Jesse Judd, Mike Nowson, Anthony McPhee, Catherine Rush, Michael Wright, Adrian Gray, Susannah Kitching

- Landscape architect

- Rush\Wright Associates

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Building surveyor

PLP Building Surveyors & Consultants

Civil and electrical engineer Connell Mott MacDonald

Conservation Allom Lovell & Associates

Electrical and mechanical engineer Scott Wilson Urwin Johnston

Exhibition designer Cunningham Martyn Design

Irrigation Landscape and Irrigation Services

Quantity surveyor Rider Hunt

- Site Details

-

Location

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Landscape / urban

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Sep 2003

Words:

Andrew Benjamin

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2003