Oblique view of the main street facade “city wall”, with the house above and behind. Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall.

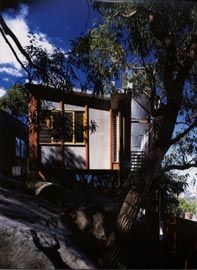

The terrace and east facade. Image: Richard Glover.

Looking east along the upper level of the lightwell within the “thickened” wall. Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall.

Looking west from the main bedroom, through the lightwell/circulation space to the eucalypts beyond. Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

Ground floor, with the dining room to the left and slatted timber stair sandwiched between the thick brick walls. Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall.

The timber stair ascending to the upper level becomes a bench within the ground floor living space. Image: Richard Glover

View along the lightwell/circulation space within the “thickened wall” formed by the exterior glazed brick wall and the internal wall of red and painted brick. Image: Richard Glover

Sandstone boulder framed by the library window. Image: Richard Glover

The living area, with slatted bench, and terrace and city views beyond. Image: Richard Glover.

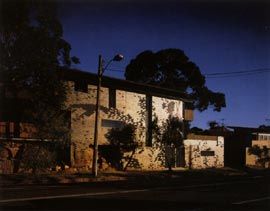

Views of the “city wall” main street edge. The abstracted pattern picked out in glazed and matt black brick reads differently according to time, viewpoint and light. Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

Views of the “city wall” main street edge. The abstracted pattern picked out in glazed and matt black brick reads differently according to time, viewpoint and light. Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall

The west facade seen from the bridge approach. Image: Patrick Bingham-Hall.

At one point during a wide-ranging conversation, gathered around the very convivial breakfast table of Peter Tonkin and Ellen Woolley’s new Lilyfield House, Tonkin described the work as “a funny little brutalist castle”. This affectionate description is apt indeed, and serves well here as an entry point for placing the work in a wider historical and theoretical context. There are many other interesting aspects that could be pursued – the process and dynamic of two architects designing their own house together is clearly fascinating, as is the relationship between this and the same architects’ earlier Killcare House – but those will have to be other stories for another time.

The house has an unmistakable alignment with the architectural movement that Reyner Banham termed Brutalism in 1955. As well as being associated with the Independent Group’s broader interests in the interrelationships between art, architecture and the everyday, this movement was distinguished by its emphasis on self-finishing, even crude materials, and a kind of brutal honesty in the expression of structure and services. The Lilyfield house is perhaps a little too refined to be truly Brutalist, but it does share some significant commonalities. These include its lack of fussy preciousness in materiality, the use of concrete in its raw form – the oversized, projecting gutter that runs the length of the house is a case in point here – and a certain more general attention to the object character of art and architecture. But while many of the materials are hard-edged, the house also has moments of lightness and delicacy; it may put on a tough front but is nevertheless also a “little castle” in the homely sense. The building is also physically castle-like – crouching above and behind a high rampart, which the architects conceive as a kind of “city wall”. Directed to the adjacent main road and railyards, and further to the distant city, this face has an important role as a screen or filter from the proximity and density of passing traffic. This has been accentuated in the planning by the “thickening” of this edge, and by stacking the resultant three-storey lightwell with an infill of slatted timber stairs and circulation, sandwiched between two thick layers of masonry.

To an extent, both the “castle” and “brutalist” characteristics of the building were suggested by the site, which is of the kind that makes architects salivate but gives everyone else palpitations. A steep cascade of sandstone outcrops on a narrow wedgeshaped block, overshadowed by a two-storey house to the north and bounded by a major thoroughfare, it presented considerable challenges. But the possibilities were also manifold: distant views of the city and harbour bridge, a stand of mature eucalyptus on the western end of the site, and the sandstone outcrops themselves all promised great rewards if they could be well negotiated. And the house has made much of these opportunities, in a way that is modest in all the best senses of the word: bold but not braggardly, straightforward but unassuming. It has a robustness that has nothing to do with arrogance, and everything to do with strength and lack of pretension. The quality of some of its detailed design is also revelatory. Who would have thought, for example, that the disposition, between two bedrooms, of a shared bathroom could be so well and thoughtfully resolved, and indeed so beautiful? The integrated lighting design is striking, as is the craft demonstrated in construction (Drew Heath acted as builder), and the outstanding precision of Shane Norton’s brick laying. The house is also modest in terms of its scale: on a tight site, the architects have fitted a three-bedroom house, a workroom and library, comfortably proportioned living areas opening to an outdoor terrace, and even a “grotto”, amongst other things. And all this while retaining almost all of the significant sandstone boulders on the site.

Another way that the building is self-effacing is in terms of its anonymity, the ability to fade into the background – approaching from its suburban street address the house is virtually invisible until one picks one’s way around a boulder and down a set of bush stairs to the entry bridge. It is also very easy to drive past along the main road without noticing it at all, its disguise as an industrial facade or one of Sydney’s remnant rock walls is almost complete. But there is more to this wall than initially meets the eye – because it is here that the house makes its one singular gesture in the patterning of glazed and face black bricks on the building’s long southern facade. While rumours have been rife about what the abstracted brick pattern actually represents, this is in many ways beside the point: it is not the figure itself that matters, so much as the effect. And this effect is, among other things, one of camouflage – the play of light across the matt and gloss bricks changes with time, viewpoint and ambient light in a way that evokes, as Woolley notes, the dream-like pattern of passing clouds. It is also, on another level, simply a way of texturing and modulating a large expanse of brick. The image clearly has a private significance and meaning for the architects, and for this reason its precise source is best left unstated. But it is interesting and important to note that the pattern does have a figurative or representational aspect, and that it is taken from a masterpiece of Italian painting. There could be many recent architectural precedents for such an approach: ARM’s experiments with photocopier and pixilation in projects such as “Not the Vanna Venturi House”, and Herzog and de Meuron’s use of applied images in projects such as the Ricola Europe factory and Eberswalde Library are just two of the most obvious. But in the Lilyfield House the strategy appears to be less about ideas of appropriation, and more about the longstanding philosophical relationship between painting and architecture.

Given that, in this case, the “painting” is thickened and given form. Picked out in monochrome bricks rather than applied to the surface, the image itself becomes an architectural material. This image/wall becomes both a screen and an “enigmatic billboard”, both a gift and a deflection to passers-by. The house thus begins a complex, if quiet, interplay between material and image, object and experience. It reinterprets the classic Brutalist strategy of roughening the skin of the object in order to point to its material. This “thingness” or object character is also revealed particularly acutely at one other point: in the library on the entry level a wall of glass faces directly, and closely, onto a huge sandstone boulder. It is as though the solidity, massiveness, and sheer crude materiality of the rock comes face to face with the more refined, but still tough and rugged work of architecture, and they share a wink of mutual recognition.

It could be argued that it is precisely this “being-for-itself”, and the building’s semiindustrial aesthetic, that are also responsible for its success as a frame for art. The house is literally full of paintings and sculpture, and the building acts to house Woolley and Tonkin’s extensive collection without competing or drowning it out. One almost has the sense that, rather than a house filled with art, this is a small, private art gallery which, as it happens, people can also comfortably inhabit. There is even a direct reference to John Soane’s house/museum in London; a series of overlapped sliding screens between the second bedroom and third bedrooms each has its own “hang” of paintings. The installation of the collection was clearly an important step in the completion of the house – almost the prerequisite to its being “finished”. In looking at photographs (as published here) that were taken before all the art was hung, it has a raw, naked quality that is quite unlike the warmth and richness of the fully installed thing. Overall, the project thus opens a debate about the relationship between art and architecture, at the level of material, representation, and contents. The idea that the building may lack a conventional architectural “prettiness”, that it refuses to pose for the camera and is difficult to fully appreciate except in the flesh, seems a small price to pay for this other, much more interesting and important discourse.

Naomi Stead wishes to thank Dr John Macarthur for his insightful ideas and teaching on image and material, and on the object character of brutalism, which have informed this review.

Credits

- Project

- Lilyfield House

- Architect

-

Ellen Woolley and Peter Tonkin

- Consultants

-

Builder

Re form - Drew Heath, Shane Norton

Environmental engineer Steensen Varming

Structural engineer Taylor Thomson Whitting (TTW)

- Site Details

-

Location

Lilyfield,

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses