As a boy growing up in Adelaide, I always admired the handsome tan brick volumes of Adelaide High School. With the languid sweep of its long, low wing facing the main road, and the blocky communion of blank cube and half-cylinder asymmetrically balanced around the main entrance, the building projected an urbane self-confidence that made it feel both out of place and completely at ease. Perched in the midst of a diffuse park landscape on the scrappy western edge of the city, overlooking the scenes of Adelaide’s automobile desert along its degraded West Terrace with an air of detached bemusement, it had a geometric lucidity that compelled respect through rational lines of brick rather than asserting authority with the mouldering stones of tradition.

Those original lines were drawn by Sydney architects Edward Fitzgerald and John R. Brogan as part of their winning entry in a national architecture competition staged in the closing years of the 1930s. Their entry was explicitly progressive in aspiration. The scheme was an unapologetically modernist proposal, expressive of circulation and functional organization through its linear wings, horizontal glazing and cylindrical stair blocks. Detailed with an eye towards Art Deco and the soft-core Dutch modernism of Willem Dudok, it was above all “practical.” The architects’ design statement described “a place of light and colour combining strength with lightness and sufficiently monumental to be worthy of an important public building.” 1 This was an architecture well suited to that particular combination of frugality and progressive idealism peculiar to Adelaide.

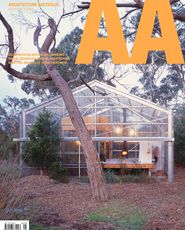

Large precast concrete panels, carefully colour-matched to the heritage buildings’ brick, wrap the volume of the New Learning Centre.

Image: Sam Noonan

Over the years the original scheme – consisting of the sweeping, curved main block facing east towards the city, two linear radial wings extending westward into the parklands and a school hall adjacent to the entrance – has been extended repeatedly, with varying degrees of sensitivity to the original architecture. The Adelaide High School New Learning Centre (or, as officially christened, the Charles Todd Building) is the latest and perhaps concluding contribution to the school’s built form. It was designed by JPE Design Studio, operating under the direction of Adrian Evans, a former student of the school. Could this full-circle return yield the phenomenon of a building – through its influence on its own future architect – acting as a self-replicating architectural machine?

Even without considering the building’s status as a state heritage item, at the level of massing the clear logic of the original plan would seem to permit little alternative. The new work attaches a three-storey linear volume to the southern end of the sweeping circulation spine, as a third radial wing of similar proportions to the two original wings. A suite of library, learning and teaching spaces is housed in the new wing, propped above a concealed car park and capped with an accessible open roof terrace.

Timber decking on the outdoor area of the roof terrace provides an informal meeting space for students.

Image: Sam Noonan

It is in the materiality of the cladding that a more noticeable departure has been made from the existing language. In place of the brick ubiquitous elsewhere, here large precast concrete panels, carefully colour-matched to the brick, wrap the volume. Precast has almost become a commercial architecture vernacular in Adelaide – it is often said that the quality of Adelaide’s precast concrete is the best in Australia. However, with its smooth, uninflected surfaces and its polite chamfered edges, precast concrete in its generic state offers little by way of tectonic character to match the knitted texture of a brick wall or the fine gridded fretwork of metal panels. The designer inevitably looks for an ornamental flourish to articulate all those bald surfaces. Here it is found in a horizontal channel shadow line detail that is applied relentlessly along the long elevations, including running seamlessly through the glazing panels. The source of this design motif is the continuous raked horizontal mortar joints of the original building. While we can grasp at a conceptual level how this gesture serves as a link back to the horizontal lines of the original, in terms of tectonic feel, the change of scale and the industrial polish of the materials weaken the aesthetic harmony of the connection.

The continuous raked horizontal mortar joints of the existing buildings (right) inspired the horizontal channel shadow line detail that runs along the elevations, including running seamlessly through the glazing panels.

Image: Sam Noonan

While the exterior seeks to soften and bridge the differences between the old and new, in the interior design, which was overseen by practice principal Josephine Evans (Adrian Evans’ daughter), the disjunction is more readily apparent. Progressive ideas in school design in the 1940s meant hard-edged, green-toned, clerestory-lit corridors, spatial hierarchies to reinforce institutional authority, and regular room configurations – aspects that reinforced the modernist spatial language of linearity and geometric form. “Innovative teaching and learning” is today’s equivalent of the “progressive education” of the 1930s, which in spatial terms translates to flexible spaces, moveable partitions, reading nooks and informal learning places, all bathed in a warm technological bath of wireless connectivity. Such ideas are manifested here in what the designers call “dynamic walls” separating learning spaces from corridors, which are thickened and modelled to yield a series of places for seating, working, gathering and display. In the architect’s words, these “dissolve the conventional idea of the classroom and corridor.”

Students occupying window seats in the first-floor Resource Hub face the neighbouring heritage building.

Image: Sam Noonan

This aspect of the design, in which partitions and other space-defining elements of the interior begin to be rethought as large-scale pieces of furniture, is where the scheme starts to innovate in architectural terms and offers promising directions for developing in future school projects. Students and teachers I spoke to were enthusiastic about their new spaces, and Josephine Evans told me how gratified she was to see the study recesses in the corridor walls being happily used by the students. However, the implementation of such ideas here remains tentative and limited. Their potential for transforming educational practice awaits a fuller, more complete realization.

While the new building appears grown from the same seed as the original, what is revealed on closer inspection is just how far the constructional and spatial dimensions of educational architecture have changed over the past 60-odd years, complicating any straightforward attempt at continuity of design. Such change, no doubt, is the only thing that remains eternal.

1. Architecture , 1 December 1940, 251, as referenced in Adelaide Park Lands: Community Lands Management Plan – Tambawodli (Park 24), a report to Adelaide City Council, 2005, Appendix 24, 7.

Credits

- Project

- Adelaide High School New Learning Centre

- Architect

- JPE Design Studio

Adelaide, SA, Australia

- Project Team

- Adrian Evans (director in charge and design architect), Josephine Evans (interior architecture design leader), Stephen Muecke (project architect and documentation leader), Peter Ahladas (site architect), Amy Pfeiffer (landscape architecture leader), Lisa

- Consultants

-

Acoustic engineer

Marshall Day Acoustics

Archaeological consultant Australian Heritage Services

Disability access consultant Davis Langdon

Electrical, mechanical, hydraulics engineers Lucid Consulting Australia

Fire engineer Lucid Consulting Australia

Heritage consultant Bruce Harry & Associates

Planning consultant Masterplan

Quantity surveyor WT Partnership

Structural and civil engineer Combe Pearson Reynolds

Traffic consultant Phil Weaver & Associates

- Site Details

-

Location

Adelaide,

SA,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 2015

Category Education

Type Schools

Source

Project

Published online: 13 Jan 2016

Words:

Julian Worrall

Images:

Sam Noonan

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2015