In ARM’s projects there is a constant striving and struggle to uncover and contribute something other than what is already known. The practice has undertaken sustained design experimentation and offered speculative and deliberate propositions formed out of the fluid, messy and difficult cultural material that it believes the architect has a responsibility to engage with and to contribute to. Far from remaining on the drawing board, these ideas and experiments have led to buildings, have been explored within a commercially thriving practice and have been convincingly furthered through the myriad of contingencies that force themselves on a building’s execution. ARM’s contribution to knowledge has been developed across a range of media and in a specific, vibrant and self-consciously polemical culture of ideas in Melbourne that it has cared enough about to contribute to and nurture.

Melbourne axis collage featuring ARM projects. Original photographs by Peter Bennetts (top) and John Gollings (bottom).

Image: Composite image by ARM Architecture

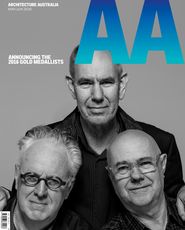

Formed in 1988 by Steve Ashton, Howard Raggatt and Ian McDougall, Ashton Raggatt McDougall (ARM) has been awarded over sixty-three state and national awards including the Australian Institute of Architects Victorian Architecture Medal an unprecedented five times. The practice’s significant public and cultural buildings across Australia include the RMIT Storey Hall Redevelopment (1995), the Shrine of Remembrance Redevelopment in Melbourne (stage one 2003, stage two 2014), the National Museum of Australia (2000, joint venture with Robert Peck von Hartel Trethowan), the MTC Southbank Theatre and Melbourne Recital Centre (2008), Hamer Hall Redevelopment (2012), St Kilda Town Hall and Library (1994), The Albury Library/Museum (2007), the Marion Cultural Centre in Adelaide (2001, with Phillips/Pilkington) and Perth Arena (2012, joint venture with Cameron Chisholm Nicol). The practice has also designed the Melbourne Docklands Masterplan (2007), Elizabeth Quay in Perth (2016, with Taylor Cullity Lethlean), Gold Coast Cultural Precinct (masterplan completed 2015), the Victorian Desalination Plant (2013, joint venture with peckvonhartel) and a series of residential towers, and redeveloped the Melbourne Central Shopping Centre (stage one 2005, stage two 2012).

These buildings, which have been highly awarded by ARM’s peers, are often not without some controversy. “Not For Everyone” the ARM website observed for a brief moment in time. While ARM is known for its fearlessness with architectural language and form, its experimentation with generative and digital techniques, some assertive and politically charged propositions and a certain wit in the work, there are other facets to this practice that have not been as well understood, yet are a core part of its strong contribution to Australian architecture.

Architecture as cultural production and the role of the architect

ARM has demonstrated a specific and sustained view of what architecture as a discipline should strive for and be, what an architectural practice does within that view and what the role of the individual architect is. Ashton, Raggatt and McDougall see architecture as a part of a wider cultural production. They believe in architecture’s ability to tell stories and engage in a culture’s shared hopes and dissatisfactions, and that it does so through its material (and immaterial) form. They also understand that, even though the possibility of doing this is elusive, the attempt is important and highly productive. To them, the architect (always defined as one engaged with many others as opposed to the sole genius) has a responsibility to contribute ideas to the discipline and the wider public realm, must fully engage in the culture of the place in which they work, and should polemicize. To ARM, architecture can’t help but be politically engaged and the architectural project means something much greater than itself. The architectural project always does these things, of course, but ARM is self-conscious about this and makes it a deliberate and operative act in its work, believing that it must also subsequently be unpacked and disseminated. ARM believes in discourse.

MTC Southbank Theatre and Melbourne Recital Centre, Melbourne (2008).

Image: John Gollings

The idea of cultural production has been explored across a range of media and outlets. Raggatt and McDougall have been Adjunct Professors at RMIT since 1993, where the ARM practice studio now runs each semester and the annual ARM-sponsored Prize For Design Excellence is awarded through the presentation of a large, game-show-style cheque at the end-of-semester exhibition. Raggatt and McDougall taught influential architecture studios at RMIT in the 1980s and 1990s as well as one of the first RMIT Master of Urban Design studios in the early 1990s. They both also made an impact, for a brief period in the early 1990s, as visiting professors at UWA. Emma Jackson, then a student of theirs at UWA, says their ideas empowered the students and opened up the perspective of the school: “Ian McDougall and Howard Raggatt blew open the scope of things we had to play with; they brought cultural investment, fight and humour to the design process. They brought a whole new level of fierce and dirty to the table, which meant that more of us could have a go, swerve, miss, and have another go.” More recently McDougall returned to his home town of Adelaide to act as Professor of Architecture at Adelaide University. Colleague Tanya Court describes “an inspiring and knowledgeable design teacher [whose] seven-year commitment to the commute to Adelaide was an incredible effort and sacrifice.” McDougall was heavily involved in the recruitment of new design-focused staff, and in bringing key design practitioners to Adelaide and re-engaging the school with local architectural practice. Court says that McDougall made “an enormous contribution to the culture of the school at a difficult time in the school’s history.”

A responsibility to communicate

ARM treats ideas, knowledge and technique as things that should be discussed and made visible, a belief that goes back a long way. In the founding editorial of Transition: discourse on architecture, the magazine’s editors Ian McDougall and Richard Munday wrote of the need for architects to discuss their work with “candour” and “in a manner that [is] of use to others,” otherwise each generation of architects “hold[s] many of the same misconceptions, and make[s] many of the same mistakes as those of preceding generations, needlessly, because the record that could be made by one generation, of its concerns, acquired knowledge, and intellectual misadventures, is not made.”2 This insistence on the architect’s responsibility to be didactic and accountable, and on the visibility of discourse, is also a consistent theme of the practice.

National Museum of Australia, Canberra (2000, joint venture with Peck von Hartel Trethowan).

Image: John Gollings

The ARM founding directors and staff were key contributors and supporters of the Halftime Club in Melbourne, which commenced in the same year as Transition as a forum for recent graduates who “were immersed in the pragmatics of office existence” so that they might “help each other further their ideology and critique”3 and later expanded into a vital forum for discourse and debate. McDougall has said that, at the time, “the Halftime Club was symptomatic of the desire to talk about architecture by practitioners that had an intellectual agenda, so there was a shift towards the idea that it [architecture] was an intellectual and cultural activity that happened at the drawing board, rather than how it was critiqued in the academy and written about by critics, with the architect saying nothing. If you asked Grounds about his work he said nothing, he was mute. So that was a big shift – it actually led to discussion, talking about meaning, propositions and speculations. There was an argument.”4 McDougall took this spirit into his role as the editor of Architecture Australia (1990–92), producing a seminal edition on the changes in public architecture in Australia in the July 1990 issue coedited with Peter Brew. The issue featured Virginia Kirton, then at the Department of Treasury, discussing the social policy of deinstitutionalization and its effects on public architecture in program and representation, as well as historian Paul Fox’s now widely disseminated text on the representational role that Melbourne’s nineteenth-century institutions took in forming a civic order on Melbourne’s so-called “neutral” speculators grid. This was vital discourse for an industry journal and posited a view that the architect needs to be engaged with politics, policy and history and that buildings deliberately engage with much more than, for example, material, sunlight and detailing (ARM considers innovation in these areas to be base expectations in the discipline).

Ashton, Raggatt and McDougall have also been strong supporters of younger generations who were equally keen to contribute to building local architectural discourse. ARM was a major sponsor of a series of intelligent and ambitious local publications, including the first Backlogue: Journal of the Halftime Club (1992), essentially a self-published 300-page magazine compiled by then-recent graduates – including editors Peter Brew, Felicity Scott, Paul Minifie and Dean Boothroyd – who were highly critical of Transition’s editorial direction, as well as Pataphysics (from 1989, edited by Yanni Florence and Leo Edelstein) and later Subaud (edited by Mark Raggatt and Christos Kastaniotis) and Mongrel, a union of Issue magazine (edited by Dean Boothroyd, Conrad Hamann and Ian McDougall) and Subaud.

Because of this insistence on creating opportunities for a local culture to develop, the ARM office has drawn towards it and had significant input from many hands, all of whom have brought their own concerns to the table and helped define the ARM project – and many of whom in turn also teach, write and engage with architectural discourse.

Ideas, the need for propositions and wider agendas

Ashton, Raggatt and McDougall’s commitment to building architectural culture has been intertwined with an interest in advancing the discipline. For ARM this has involved an overwhelming and constant experimentation with process and technique – often exploiting the new tools and techniques of the time, from the slide-top photocopier, used to explore the “blur” or “speed” in the Howard Kronborg Medical Clinic (1993), to advanced digital modelling tools in the National Museum of Australia (2000). These explorations resulted in a range

of formally adventurous outcomes – often misunderstood as a sole interest in pure form – that were part of wider agendas, ideas and propositions and were not ends in themselves. In the early projects, these agendas included speculation on the role of the suburban civic project, how to work with local memories and artefacts and the complex questions raised by discourses of “the copy,” translation and legibility. In buildings such as the William Angliss Knox Sherbrooke Aged Care Facility (1992) and the Brunswick Community Health Centre (1990) and other small-scale commissions, the result was to imbue modest projects with a heroic potential – allowing them to punch well above their weight in the expanded civic and urban realm.

Brunswick Community Health Centre, Melbourne (1993).

Image: Sebastian Gollings

A number of early projects were driven by the idea of Australia’s position on the “fringe.” ARM turned a potential negative – of so-called distance – into a positive and imbued this stance with generative design potential. Techniques of sampling and appropriation evident in music and art were employed in the bunfight that was the legitimizing of local architecture. This position on the fringe was a polemical response to the uncritical transportation of architectural objects and ideas. McDougall called this “part of the illusory glamour of the replica, isolated from its history, available and titillatingly uncontroversial.”5 ARM developed a series of processes and techniques that sought to make importation explicit, often operating on iconic modernist architectural precedents. This was experimentation that was speculative, critical and self-consciously propositional and it has had a major influence on Australia’s architectural culture.

Raggatt and McDougall unpacked these ideas and techniques in their postgraduate design practice research master at RMIT. Raggatt’s “Notness: Operations and Strategies for the Fringe” (1991) and McDougall’s “The Autistic Ogler” (1994) were produced under the supervision of Leon van Schaik in the early years of van Schaik’s ambitious project (which continues in its maturity at RMIT as an international Design Practice Research PhD program) in which a series of distinguished practitioners are invited to examine and reveal the knowledge found in their architecture, make this visible and, with a renewed understanding, speculate through new projects about future trajectories for the work. These documents were highly revealing and influential and were even more vital in that pre-internet era, when there was so little available on contemporary local architecture, particularly anything that gave insight into the hows and whys of designing. Raggatt and McDougall also, through example, demonstrated how one might structure experimentation around a critical design practice that is itself engaged in wider cultural terrains, and how the architectural projects might be at the centre of such propositions.

Future terrain

The projects that Ashton, Raggatt and McDougall oversee as ARM illustrate how we might achieve an interwoven and complex relationship between ideas, techniques, processes, critique and the performative ambitions for buildings and their delivery – and how we might take the clients along with us in the process.

It is astonishing to consider that one practice can engage in such a dense and sustained level of experimentation and production of knowledge and ideas. ARM’s influence on Australian architecture is not an influence of form or style but of ideas. This is not a practice that requires the genius sketch of one director to progress a project. This is the articulation of knowledge, techniques and ideas that others can understand, engage in and progress – or alternatively take issue with. As individuals, Steve Ashton, Howard Raggatt and Ian McDougall have independently made significant contributions to the discipline and the profession. Together as ARM Architecture, they have articulated another important and ambitious project in a way that others have been able to engage with and contribute to developing, and its influence on Australian architecture continues to run deep.

1. “Building the Impossible” and “Making a Culture” are both ARM terms. See Mark Raggatt and Maitiú Ward (eds), Mongrel Rapture: The Architecture of Ashton Raggatt McDougall (Melbourne: Uro Publications, 2015).

2. Richard Munday and Ian McDougall, “Editorial,” Transition: discourse on architecture, vol 1, no 1, July 1979.

3. Grant Marani, “Halftime Club Charter 1979,” published in Dean Boothroyd and Gina Levenspiel (eds), Backlogue: Journal of the Halftime Club, vol 3, 1999, 128–129.

4. Ian McDougall in Mark Raggatt and Maitiú Ward (eds), Mongrel Rapture, 704.

5. Ian McDougall, “The Autistic Ogler” in Transfiguring the Ordinary: RMIT Masters of Architecture by Project, Leon van Schaik (ed), (Melbourne: 38 South Publications, 1995).

Source

Discussion

Published online: 2 May 2016

Words:

Vivian Mitsogianni

Images:

Composite image by ARM Architecture,

Courtesy of ARM Architecture,

John Gollings,

Photographer unknown,

Sebastian Gollings

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2016