Unwilling or unable to understand its own knowledge base, the architecture industry has failed to make society at large aware of the case for higher order spatial thinking. The cultural project of architecture, its capacity to capture and further our aspirations, is all too often neglected. How wonderful it is, then, to come across a project that most Australians could afford, that is practical and witty, that situates itself in the history of the shed in architecture and expresses a family’s intergenerational interest in art. How did this project come about? A family grew up in Melbourne; the parents had interests in the arts; the mother painted; some of the children painted. The children made friends with – among others – architects Peter Hogg and Toby Reed. Time passed and the father, widowed and living on a wooded block in a small village in central Victoria, sought to remember his wife and the love of painting she had engendered. The idea sparked a suggestion from his children that he ask their architect friends to create something appropriate, albeit with a very modest budget – marginally more than would purchase and insulate an off-the-peg shed.

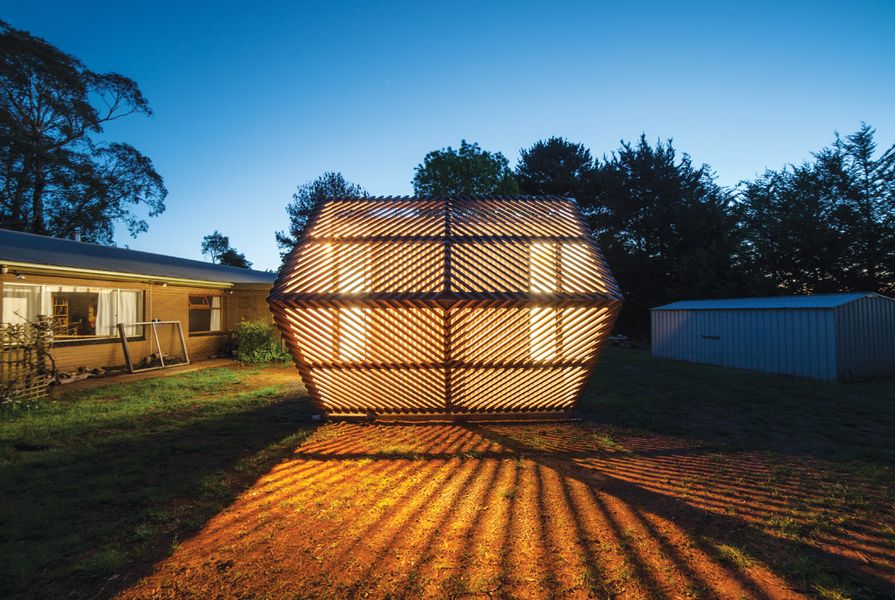

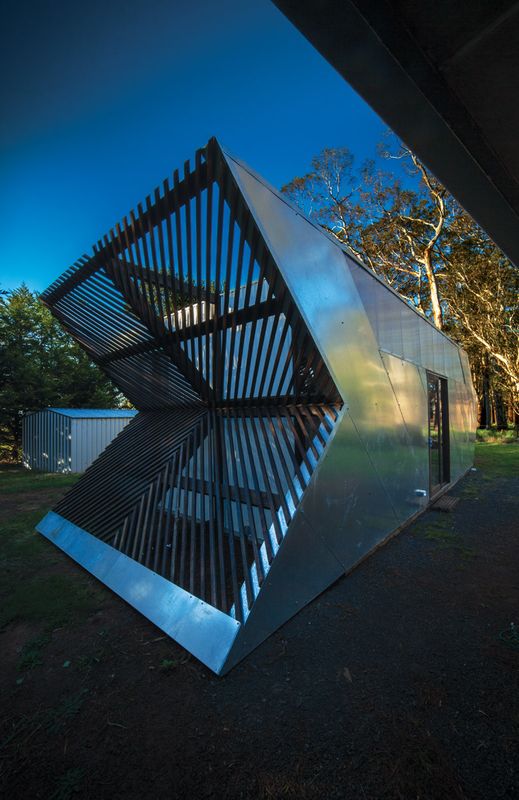

Diagonal bands of galvanized sheeting wrap the structure, which has been built using passive house technology.

Image: Sam Reed, Toby Reed

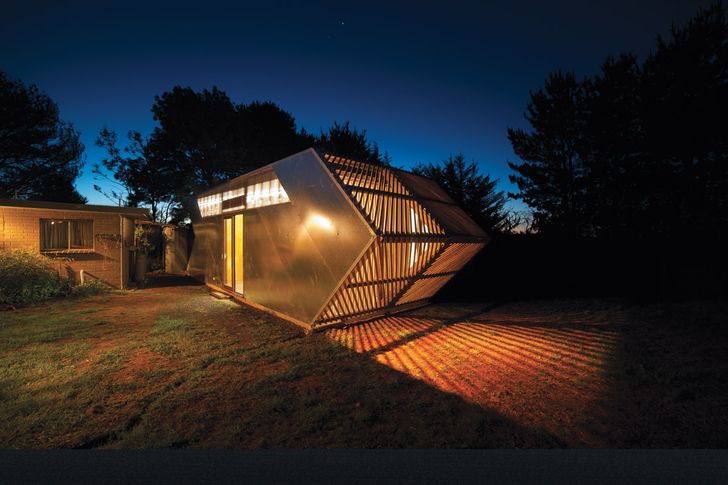

At the time of the commission, architect Toby Reed and his partners were already engaged in designing and building a series of passive houses using new German technology. To meet the target budget for this four-by-eight-metre gallery, some deft manoeuvres were needed, separating the design and construction processes but linking both to the studio’s experience with this new German technology. The builder, who was adept at using the technology, was preselected. Off-site and in the advanced technology context, the design was finalized. Plywood has been used structurally and the highly insulated walls and roof are sheathed in galvanized sheeting lapped diagonally. Narrow vertical windows that maximize wall space, ventilate, ensure security and admit light along the longer walls, Venetian-style, puncture the end walls. Timber battens provide shading and screening at each end, convexly to the east and concavely to the west. A south-facing clerestory window in polycarbonate, with the entry door below, completes the ensemble. The gallery is sited at a slight angle to the house, and beyond it there is indeed a bought shed.

So much for the pragmatics. What has been provided is a shimmering architectural wonder, an object – as the architects intended – of “pure beauty” that captures the imagination with its suggestion of being a Winnebago, casually parked, evoking thoughts of journeys completed and those to come.1 From some angles it seems almost monumental in scale and at night it phosphoresces like a recently landed spaceship. Inside, pictures hang on the walls in the process of being curated, old chairs make it homely and it is always coolly comfortable. Happenstance? Not at all. The architect, versed in the companion arts of art and filmmaking as well as in his own discipline, was completely aware and calculating in designing this tiny gallery. A constructed north point arrow, the building hovers between being an “image” – that anathema of 1960s minimalism – and being an industrial object of simply utile beauty, eschewing reference to anything other than itself. And yet the square elevations of the convex and concave ends are divided and barred up diagonally but in reverse to each other, one making the Renault symbol, the other that of a reflected Citroën logo. Signification, this architect knows, is inescapable. The valency of Arrow in its form and in its about-to-depart siting, in its naming, in its glimmering in sunlight and in its glowing in artificial light, is a calculated scenographic construct arising from a lifetime spent in and around film. Reed’s father Colin Eggleston directed Long Weekend (1978), an environmental horror film about our relationship with nature and the bush, while Reed most notably made a 2013 documentary on Peter Corrigan, the architect whose use of imagery in his work mystifies and annoys Europeans with a minimalist bent. Arrow is unusually elusive as an object in space. Each facade reads autonomously as a two-dimensional graphic, yet as you walk around the building it seems to twitch into three dimensions at each oblique, flickering between the two graphics in view. This is an Eisenstein moment, a “montage of attractors” enjoined to create a vision in the mind of the viewer, a vision that is – as the photographs attest – uncanny and other-worldly, even monumental.

Moving around the building, the viewer perceives a twitch from two-dimensional graphic to three-dimensional form.

Image: Sam Reed, Toby Reed

And to be sure, Reed is thoroughly conscious of the arguments he is designing within. He discusses Hal Foster’s 2011 book, The Art-Architecture Complex, a discourse that excoriates the late capitalist appropriation of the image into an “architecture of the spectacle” or an architecture of “the ancient Roman panem et circenses [bread and circuses], only without the bread,”as critic Rowan Moore has put it.2 The designing considered the pursuit of pure beauty by minimalists in art and in architecture and was mindful of the critique that claws back a position for architecture as the utile art. He knows that this shed has to be in the lineage of Philip Cox’s romance with nineteenth-century wool shearing sheds and Peter Stutchbury’s luxury houses in the manner of these now romantic ruins. He knows that Lacaton and Vassal’s 1993 Latapie House at Floirac in France lurks on the mental horizon. In a sense, he paraphrases John Baldessari. “This [Arrow] owes its existence to prior [of its kind]. By liking this solution you should not be blocked in your continued acceptance of prior [versions]. To attain this [design] ideas of [the shed] had to be rethought.” Again he aligns himself with Baldessari. “A two-dimensional surface without any articulation is a dead experience.” Arrow is alive. “I will not make any more boring art.”3 Arrow is not minimalist, nor is it imagist; it hovers tellingly between these zones, it is pure magic. And it could be in your backyard …

1. Pure Beauty was the name of conceptual artist John Baldessari’s major retrospective in 2009–10 at the Tate Modern and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

2. Rowan Moore, “The Art-Architecture Complex by Hal Foster – review,” The Observer, 16 September 2011, theguardian.com (accessed 20 January 2014).

3. John Baldessari, Painting for Kubler (1967–68), A Two Dimensional Surface Without Any Articulation is a Dead Experience (1967), I Will Not Make Any More Boring Art (1971).

Credits

- Project

- Arrow Studio

- Architect

- PHTR architects

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Toby Reed, Peter Hogg

- Consultants

-

Builder

Carbonlite Design + Build

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type Small projects, Studios

Source

Project

Published online: 19 May 2014

Words:

Leon van Schaik

Images:

Sam Reed, Toby Reed

Issue

Architecture Australia, March 2014