Architects can be very dull when they go on about details. We often hear that “the devil is in the detail,” and Mies van der Rohe told us it was God in there. Yet there is something peculiarly compelling about a beautifully executed architectural detail that often remains obscure and trivial to an untrained eye. Are details a private language or a fetish of architects?

At Kennedy Nolan we do not like to think of our work as a collection of fetishized details. Our preference is to see our work as somehow more austere: details are elements that are inherently supportive rather than a feature. At the larger scale, we make architectural form a detail. A formal element in masonry can be used to enclose space, and link to context or another element in such a way that the junction is suggestive rather than contingent.

An example of this approach can be seen in the Hampton House (below), where the roughcast masonry walls are reduced to emblematic or gestural elements, which in this case reference the Edwardian context. The potency of the reference is gained through abstraction; practically, this involves editing visual distractions such as flashings, cappings, beads, frames and edges, which is where the larger detail relies on numerous small detailing manoeuvres.

Hampton House by Kennedy Nolan Architects extends an Edwardian dwelling.

Image: Derek Swalwell

Structural elements can also provide opportunities for a detail that fuses iconographic qualities with physical necessity. The need for vertical support in a delimited horizontal space at the Stockbroker Tudor House (below) suggested an element that could fulfil structural requirements while simultaneously making an object. As before, the potency of the gesture benefits from abstraction and rigorous editing of familiar constructional paraphernalia.

The “paperclip” at Stockbroker Tudor House by Kennedy Nolan Architects.

Image: Derek Swalwell

Our broad approach to detail has roots in the Arts and Crafts movements of Europe, the United States and, most influentially, England. A compelling attribute of the Arts and Crafts movement is the nuanced synthesis of many elements into a designed object that is neither representational nor narrative but focused on decorative and material concerns, or is in some cases allusive or even iconographic.

The Arts and Crafts movement also had great regard for craftsmanship. With the emergence of brutalism in the mid-twentieth century, it seemed to provide a way of synthesizing the cultural sensitivity of the arts and crafts with the social optimism and technical empowerment of modernism.

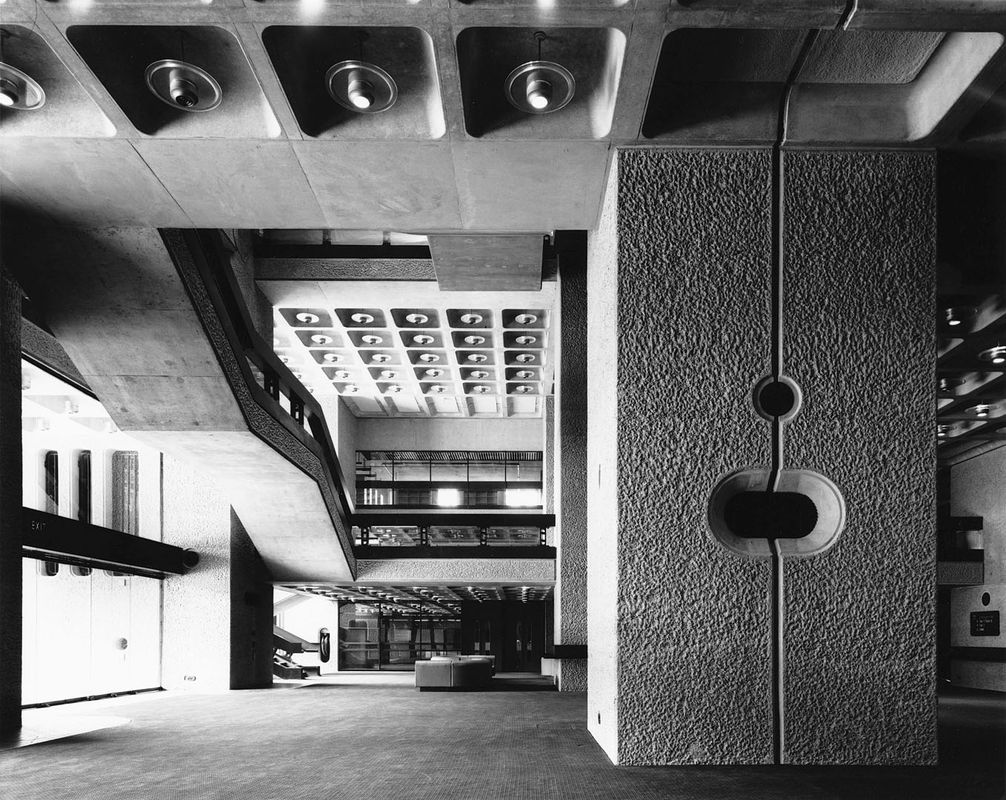

We regularly look to examples of brutalism for inspiration and to answer questions. The breadth of the movement means it encompasses a broad range of interests in our practice, but we often return to the heroic Barbican complex (below) by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon. The Barbican is especially appealing for the way that the approach to design is evident in the smallest details, such as the brass light switches rebated in bush-hammered concrete.

Chamberlin, Powell and Bon’s Barbican complex in London.

Image: Courtesy RIBA Library Photographs Collection

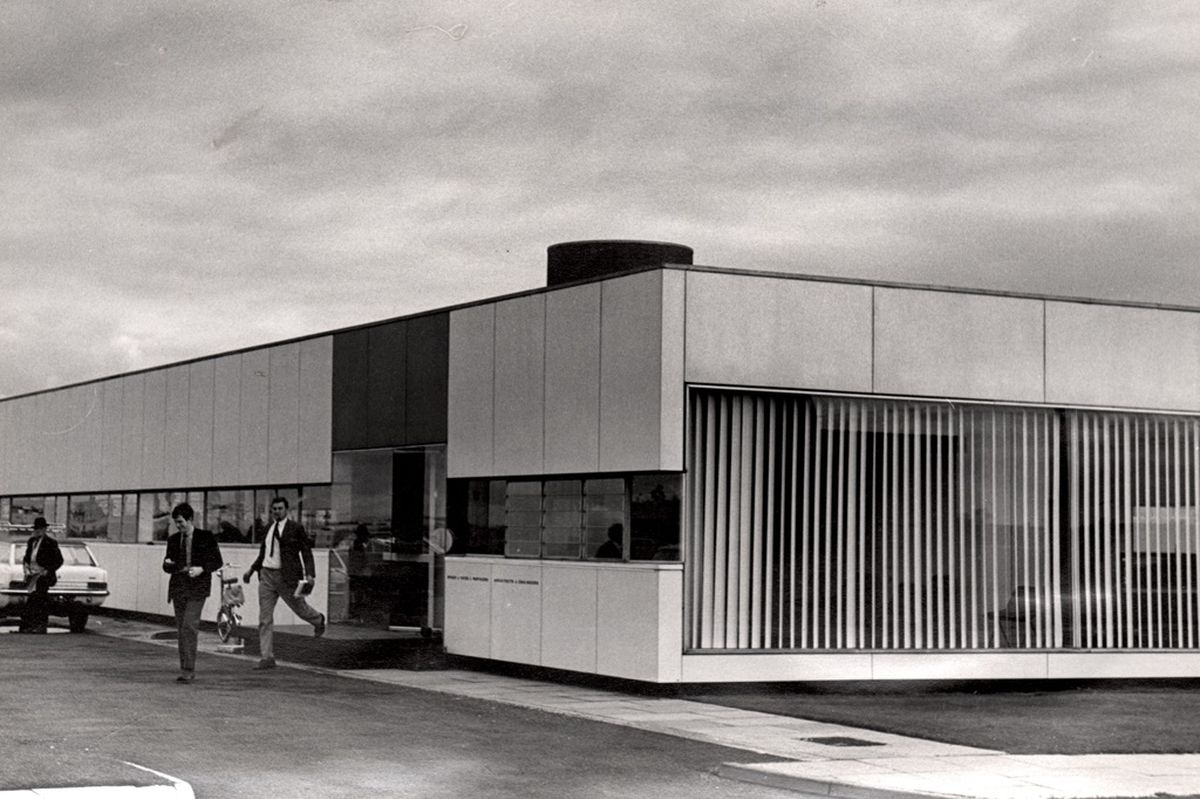

We also recently discovered the English practice Ryder and Yates. It made some extraordinary brutalist buildings that also incorporate the allusive gestures to which we are so drawn. We became aware of Ryder and Yates after Allan Rodger, who taught us at the University of Melbourne, recalled the practice to us after seeing our retrospective exhibition at the university last year.

Ryder and Yates’ housing at St Cuthbert’s Green, Newcastle upon Tyne.

Image: Courtesy RIBA Library Photographs Collection

This exhibition was an opportunity to reflect on practice. It was entered via a blind entry and consisted of a lectern of large-format plans, a wall made up of a collage of black-and-white images of our projects and a travertine plinth supporting five revolving models, each of which encapsulated formal, qualitative and iconographic interests in our practice. Explored in the exhibition was the less tangible compulsion in our work to distil the impalpable — to draw on the numinous reaches of memory; the evocative power of recognizing form, colour, texture and light; and the resonances of shared memories, of history and of landscapes.

What we are trying to do is acknowledge possible emotional connections to architecture by understanding that people don’t experience or remember like a video recorder. Rather, we experience and remember in fleeting moments and snapshots, and architecture can support this and also relate to wider cultural influences. This all sounds very highbrow and worthy, but in reality it is achieved by pursuing a design process that has evolved through years of practice.

A retrospective exhibition of Kennedy Nolan Architects’ work.

Image: Michael Blamey

As we embark on making larger buildings the compulsion to synthesize many elements in nuanced and non-narrative ways continues, but the method of making changes radically as we encounter different technology and construction. So far our approach is to learn about the capabilities and qualities of the constructional palette available and to deploy the materials and trades in a way that supports their inherent qualities and strengths. In other words, we return to the question asked by Louis Kahn: What do you want, brick?

Source

Discussion

Published online: 7 Mar 2013

Words:

Rachel Nolan,

Patrick Kennedy

Images:

Courtesy Newcastle Library,

Courtesy RIBA Library Photographs Collection,

Derek Swalwell,

Michael Blamey

Issue

Architecture Australia, November 2012