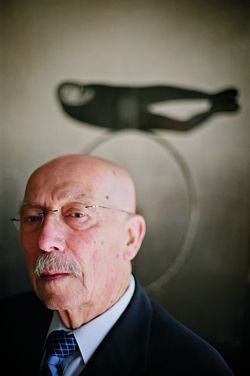

Enrico Taglietti, 2007 RAIA Gold Medallist. The background image shows a work by sculptor Rod Dudley. Part of a poster from the Bonythorn Gallery, 1973. Photograph Vikky Wilkes.

Enrico Taglietti, “a senior member of the profession with a gold medal around his neck”, reflects on the state of the profession, and outlines his hopes for Canberra.

Since 1972, the Gold Medallist’s brief for the AS Hook Address has been to provide insight into their life works and principles, and to comment on the current state of the profession. Since 2005 Gold Medallists have also been asked to visit all the states and territories and humbly talk about themselves and the greatness of their work(?). I have been privileged to tour this great land of ours during the last six months. It was hard work and almost impossible to awaken at ungodly hours of darkness. But it was enlightening and nine times out of ten well organized.

This evening I will not repeat my life story nor show my works. Instead I will direct this talk toward the state of the profession as I see it. My address will touch on five areas: postcard notes from the cities of my tour, the RAIA’s role as a protector of architecture, the aloofness of architecture, the architect’s trade, and the “mega cities” syndrome. I will conclude with the enveloping utopia, and my invisible city.

Not being an historian, an academic, an orator, and sometimes having doubts of being an architect, my address can only represent an opinion of a senior member of the profession with a gold medal around his neck.

Postcard notes

Alfred Samuel Hook, from J. M. Freeland, The Making of a Profession (Sydney, Angus & Robertson, 1971).

Departure Lounge Melbourne. In the street in a tram, a real tram, we enjoyed the ride – we felt part of the new citizens of the world, “tourists”. In the evening, a cocktail at the top floor of the “highest building in the city”. The taxi driver had never seen it before. When we arrived the floor was crowded; we could not hear any question directed to us, but we knew that the answers we gave could safely be hypothetical. The dinner was late, but effervescent. The guests were speaking in Japanese, Finnish, Italian, English and some Australian. Timothy Hill the perfect host.

Sydney. When we arrived in Sydney over 50 years ago it was a civilized old city. Everyone seemed to be interested in us. In the lift of the Australia Hotel, a sign asked you to keep your hat on or off. Today Sydney is another mega-city; the smell of fumes and the tunnels are invading every space. In the lift you can keep your hat on, nobody seems to notice you anyhow.

The taxi to Tusculum was very late and it was not even raining. The architectural community was apparently considered too busy to be invited. Therefore, the theatrette was not considered the proper venue and a room with a dozen chairs was thought to be “cosier”.

Brisbane. Last time I was here it was “Expo time”. Now the river’s west bank awaited us in all its splendour of new buildings. The city street names again reminded me of old times when ladies and gentlemen kept a certain respectful aloofness, with men northbound and ladies eastbound.

The talk was well attended and the president Ian Mitchell and three Gold Medallists – Robin Gibson, Brit Andersen and James Birrell – welcomed me among them. I could not have been better supported than by the relentless, witty remarks of Timothy Hill.

Hobart was for a time my second habitation. Mount Wellington still acts as a weather oracle for every six-hour period of the day. The Aurora Australis is still anchored in Salamanca Place ready to sail to Antarctica. James Jones and many old friends were there; we watched the trawlers bringing in the early morning sea catch and I almost lost my medal in the freezing process.

Darwin. Crocodiles, festival time. At dinner President Ross Connolly called everyone Ross, it was a bit confusing, especially as I was given this honorary name too. Troppo Architects showed us the Troppo-city. Gregorio and Lena were delightfully informative and the Troppo architecture is Troppo-cally attuned.

Adelaide. Old university and new one. Bob Hawke was in town to open the UniSA Hawke Building. It was enlightening to revisit the city after Don Dunstan. Sipping a glass of Grange among a group of architects practising Italian dialect with me – President Andrew Vorrasi, Antonio Giannone, Nick Tridente.

Perth. The conclusion of the tour. I visited Perth 45 years ago, when I joined my young family coming back from Europe by ship. No skyscrapers then. Rod Mollett, the president of the WA Chapter, still remembers catching prawns in the river and still treasures his net. A great tour of the city was organized by Rod, Sasha and Daniela. The evening of my talk was also the inauguration of the WA Chapter’s new premises. David Parken was present. Gary Hill was also present and became a grandfather on the night.

Generally, in every state, everyone attending the talks, architects or not, all showed a great sense of pride in their achievements, in their atavistic origins and in their Australian belonging.

The RAIA as a protector

My Melbourne talk was held at the Departure Lounge convention. Predicted to be too peculiar to be properly attended, in fact more than a thousand were present. Timothy Hill reminded the assembly that “How we practise can make as much difference to the built environment as our talent or our taste, our tendencies or our architectural theories.” Talking of architectural theories and trying to interpret Alfred Samuel Hook’s aims, I would like to express my view on the role of the RAIA as the protector of architecture.

In the 2008 RAIA Strategic Plan the aim of the Institute’s mission is specified, inter alia, as to “Expand and advocate the value of architects and architecture.” Architects, certainly – but architecture? Books have been written on the subject of architecture.

Remember Louis Kahn?

“Architecture has existence but no presence. Only the architect’s works have presence. Those works are made as an offering to Architecture at the urging of industry, and when the dust settles the work gives the sun its shadow.”

Remember Lao Tzu?

“To make a building, You cut-out doors and windows in order to have light. You adapt the Nothing therein to the purpose in hand and you have the enjoyment of the building. Thus what you gain is something. Yet it is by virtue of the nothing that the building can be put to use.”

Remember Socrates? Most of the people, planners and architects, are chained inside a cave in such a way that they can see but shadows. Only a few escape to reality. At first they are blinded by the light but they recover and Socrates says to them,

“At last you saw the invisible. The prison house is the world of sight, the light of the fire is the invisible and you will not misapprehend me if you interpret the invisible to be the ascent of the soul.”

The Socratic “invisible soul” of architecture, Kahn’s the “no presence” of it and Lao Tzu’s “nothingness” are only a few of hundreds of fascinating aspects of architecture – all worthy of debate, but their definitions will always be subjective and philosophical.

I am sure A. S. Hook would agree with me that architecture’s essence should be left to be argued between architects, philosophers and historians, and that the Institute’s mission should never consider entering the minefield of architectural philosophical theory. Rather, the Institute should do all it can to support architects in doing what they do best.

So may I suggest this evening a plain substitution of the words of the Institute’s mission statement – “expand and advocate the value of architects and architecture” should read “expand and advocate the value of architects and their works.”

The aloofness of architecture

Let me dwell now on architecture as I see it. My theoretical approach is to design the emptiness within the building, the Nothing which silences reason, to create a theatre, a circus, where questions are more important than answers.

Architecture to me is the shaping of voids – you carve their connections and you surface their limits with appropriate materials. Architecture is an open work and it is the inhabitant’s emotional response to it that reveals it.

The Socratic invisible within the voids should be speaking to them, listening to them and responding to their emotions. To me, this is the aloofness of architecture and its essence.

The architect’s trade

I have been often asked what the architect’s trade is. My answer is, “A balancing act in order to see buildings giving the sun its shadow, and at the same time to be approved by the local authorities in reasonable time.” After all, our trade is not so difficult as suggested by Vitruvius 1600 years ago: “An architect should be healthy in body, a man of letters, a mathematician, a diligent student of philosophy, familiar with history, a skilful draftsman, acquainted with music, not ignorant of medicine, learned in jurisprudence, familiar in astronomy and astrology and the movement of heavenly bodies.”

Mega-cities, non-cities

The world’s gurus have suggested that if we do not expand, and create monetary wealth, and if we do not reduce our pollution to a sustainable level we will all perish, hoping to become rich.

Let’s have a go, let’s be wrong for once, let’s kill the Buddha. Let’s consider the absurd, but bear in mind that the absurd is only ridiculous when it is seen from the wrong angle. Take Einstein, for example. He proposed then-nonsensical notions – that the speed of light was a constant and that the ether did not exist, and the invisible was revealed. As we all know, Einstein’s “absurdity” became the most famous theory known to humanity: Energy equals the mass by the square of the speed of light. E=Mc²

Let me suggest that in relation to the world problems of climate change, pollution and overdevelopment of our habitat, creating mega-structures and mega-cities, we have two main roads to take. One is to accept the inevitable and make the best of it. Design cyber cities, mega-cities, mega-air filters, mega-spaceships. If this is the case, at least be honest and accept megalomania. Humans have always fought nature and gods. The other option is to fight the windmills and use utopia as the most efficient tool for our design’s endeavour.

The two directions will be equally challenging and visionary if properly considered. Conflict of ideas is the essence of life and our planet may be one of a million in the universe. Cities as we have known them may exist only in our memories even today.

It is for us to make a choice.

My life choice has been to pursue utopian ideals. In that vein I will conclude with my dreams about Canberra’s future planning.

My invisible city and the utopia envelope

In my peregrination I kept hearing that development is essential to the prosperity of cities, and that the adjective “sustainable” is the imperative word for our profession.

This is prevalent in all cities of the world. I am not aware of a proper study on the possibility of mutual coexistence of the two assumptions – mega-city and sustainability – but it may exist somewhere.

What I am well aware of is the planning development proposal for our capital city and I am taking this opportunity to express my heartfelt objection to it. Canberra is a unique city; it is utopia ready to be realized. It is the city of the “nowhere” when the “nowhere” is not to be found any more. The city could be the new E=Mc² of urban design – if we have the will to make it so.

In 1904 the Australian capital was conceived, more by artificial insemination than through passionate love. It took nine years to see the light and another fifty years to grow to puberty, when the golf course became the lake.

The city is now self-sufficient, and will continue to grow. But it still lacks the passion of lovers. Politician and planners do not see the invisible; they still live in the cave of the conservative, superseded visible.

Canberra is at an historical crossroad. We have a choice between healthy growth and malignant growth. Surely our first duty is to ensure that its future development be as visionary as our forefathers expected and conceived it to be. The current planning and designing philosophy of Canberra is forcing the city in the wrong direction and should be stopped. Canberra planning should strive for the sense of enhancement of the genius loci, and for eternal qualities.

Instead, the planning authorities are: adopting superseded tools to solve new challenges; using quantitative measures to solve qualitative needs; debating building height limits versus building shapes; supporting density by infill instead of parks and openness; organizing tokenistic public consultation and workshops instead of Pecha Kucha, real conversations; strangling City Hill Park with eight-storey buildings bordering Vernon Circle; surrendering the lake shore to a privileged few.

One of Canberra’s singularities is its physical confinement within the bounds of the Griffin Plan, protected by green corridors and hills creating well-defined limits of growth. This limitation, if we don’t succumb to the greed of infill, would allow an accurate determination of optimum sustainable development and a well-defined division of precincts within central Canberra.

Therefore, I suggest that the main thrust of the planning of Canberra should be the creation of architectural envelopes shaping complete precincts within the bounds of existing environmental constraints.

We should design each precinct as we would design a single building. Consider the most desirable views, the direction of the winds, the north aspect, the open spaces and the shadows and define the most satisfactory envelope. That envelope should become the controlling rule for the precinct. Divide the envelope and lease each parcel with the requirement that the development adhere to the particular voids contained in that parcel of the envelope. Lease each parcel until the precinct is completed. These are the vital correctives needed in a society which too often defines progress only with reference to economics and usually at the expense of the ascent of the soul.

The evening is too short to express all my dreams and concerns with our capital, so I will sum up by saying: make an effort to remind the politicians that Canberra is the Australian capital, not Sydney or Melbourne. Tell the planner that it is not private development that makes richness and it is not encircling Vernon Circle with buildings that will give our city a heart.

It is pursuing the dream of the invisible city, of the city of the nowhere; it is the utopia of the vision.

To conclude, I quote Sir Herbert Read: “Our Australian capital should always be the index of our social vitality, the moving needle that records the destiny of our civilization. A wise statesman should keep an anxious eye on this graph, for it is more significant than a decline in export, or a fall in the value of the national currency.”

Enrico Taglietti is the 2007 RAIA Gold Medallist.

He presented the 2007 AS Hook Address on 20 October,

at the Giralang School, Canberra.