Annie Edney has an idea to fill the foyer of the Atherton Gardens Social Housing and Hub development with art. She has another plan to use an art project to educate fellow residents about litter and the effective use of the rubbish room. As an enthusiastic tenant who is also a community-based artist, she is keen to contribute to the place she has quickly come to love. For Edney art is an important way to support the transformation from “housing” to “home” and a way to work through the teething problems that inevitably arise along the way. Her motto is “don’t complain about something until you have a solution.”

Edney is one of a number of highly active residents at the new development on the site of the former car park at the Atherton Gardens Estate in Fitzroy, Melbourne. Funded by the federal government and briefed, developed and project-managed by the Victorian government, the building is now managed by Urban Communities, a non-profit property management company.

The project provides 152 new apartments in five configurations (three one-bedroom, two two-bedroom). Seventy percent of the housing is reserved for those coming from public-housing waiting lists, with the remaining 30 percent available to others who demonstrate a need for low-cost housing. Rent is calculated as a proportion of income.

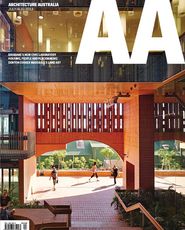

The facade echoes the strong masonry frontages along Brunswick St.

Image: John Gollings

The ground floor houses a children’s and family hub, funded by a consortium of Lentara UnitingCare, the Brotherhood of St Laurence, the City of Yarra and state- and federal-government agencies. This integrated service centre for both residents and the neighbourhood includes childcare and a wide variety of support services. Car parking is for tenants across the whole estate.

The new housing and facilities come at a time of desperate need. According to the City of Yarra, only 1 percent of the housing within its boundaries is “affordable” for those who earn less than $37,000 a year (that is, rent is less than 30 percent of income). More broadly, two recent government reports have been highly critical of the provision of public housing. The 2010 Parliament of Victoria Family and Community Development Committee Inquiry into the Adequacy and Future Directions of Public Housing in Victoria report comments on “decades of underinvestment and decreasing stock levels.” Recommendations include increasing social housing to 5 percent of total Victorian housing stock by 2030 and that the government “investigate alternative models for funding and promoting non-government investment in social housing.” The 2012 Victorian Auditor-General’s Report, Access to Public Housing,

was equally damning, finding that the government was following an unsustainable model, with no asset management strategy and inadequate planning for the future.

A colourful array of pop-out balconies on the north and east elevations.

Image: John Gollings

It is in this context that the Department of Human Services (DHS) is exploring models for increasing levels of affordable housing. The Atherton Gardens project is part of this, and the first stage of a larger masterplan that has become highly contested. Critics oppose building on open space and are mistrustful of the government, arguing that it is just trying to cash in on valuable land. We will need to wait to see how this larger debate plays out, but the project under review is certainly focused on supporting those in need while also building connections to the wider neighbourhood.

So what of the architecture? How does it negotiate this complex and difficult context, which ranges from the individual hopes and needs of tenants to wider social, economic and political considerations?

A basalt-tiled plinth base with low, recessed windows.

Image: John Gollings

Designed by McCabe Architects and Bird de la Coeur Architects (BDLC), the building is robust, carefully planned and colourful. The impacts of the tight budgets, timeframes and regulatory requirements are evident in minor ways, but overall it is a skilful project that thoughtfully accommodates both brief requirements and residents’ “stuff,” while also attending to its urban context.

Michael McCabe has worked on the project for some years, having undertaken the feasibility study that explored various sites for social housing and a community hub within the estate. The current site was identified and the concept design for the building form and arrangement completed.

Resident Annie Edney in her one-bedroom apartment.

Image: John Gollings

Funding came through the federal government’s stimulus package, which meant that the project had to be designed and documented very quickly. McCabe Architects teamed up with Bird de la Coeur. This enabled the practices to work to the very tight timeframes, but it also brought complementary skills and experiences to bear, providing what McCabe describes as “in-built peer review.” Vanessa Bird of BDLC adds that the practices “sparked off each other” in a way that was “both professionally and socially stimulating.”

The building takes its design cues from its Brunswick Street neighbours, with their strong masonry street fronts and ad hoc, “lean-to” backs. The architects developed a similarly formal front contained within a flat, decorative brick facade and a looser, informal rear. The Brunswick Street edge has a tiled plinth base – also drawn from neighbouring buildings – with low, recessed windows that provide spots for passers-by to sit, lean and linger. Above, the balconies are recessed in the manner of a loggia. Around the back they pop out from the face of the building in a busy, colourful array. The rhythm of both facade systems comes from the arrangement of the different units within, expressed by the balconies. Both balcony configurations – recessed in and projecting out – also readily accommodate the “stuff” of everyday life. Glimpses of inhabitants’ things – plants, bicycles, washing lines and all the rest – provide a secondary layer of colour and ad hoc pattern, and hint at life going on within. (Part of the DHS brief was for it to look like other multiresidential buildings – not like public housing.)

Once inside, apartments are accessed via long, double-loaded corridors. Shifts in colour give some sense of individual address, but what most effectively ameliorates the relentlessness of the corridors are the fully glazed openings at each end. These work to both open the building out to the city, and to draw the urban vista into the body of the building. (Bird points out that openable windows would have aided cross ventilation, but that unfortunately these were not possible.)

Edney generously showed me her home, a one-bedroom apartment at the “back” of the building. The apartment is tight but carefully planned and Edney has made the most of every corner. The balcony is generous enough to provide another “room” in the warmer months and affords wonderful views over Fitzroy. Edney points out where friends and artist colleagues are located. In moving here she has returned to an area she knows after living out of Melbourne for some years; she describes it as “coming home.” This circumstance might not have been possible in the booming private rental market.

Not all residents are as engaged as Edney, and some are dealing with multiple, serious problems, but early indications of overall resident wellbeing are positive. Urban Communities comments that it takes around a year to understand a new project, to really come to grips with how it is used – in both expected and unexpected ways – and with what works and what doesn’t. Urban Communities uses a range of measures to ascertain the “health” of a project – occupancy, cultural and social behaviour, and rent arrears. So far things are looking good. Occupancy rates are high, turnover is low and rent arrears are at 1 percent, which is particularly low.

Urban Communities says the main struggle in the first year is creating a sense of “home” for residents – and the comforts and responsibilities that go with this. It does this through a “place-based” system. On-site manager Nick Marandos is available for residents to drop in on with updates and new ideas, and people often do so. Over time, Urban Communities will undertake various kinds of post-occupancy evaluation. This will provide useful feedback for the architectural team, too – architects rarely have access to such detailed understanding of the ongoing lives of their buildings.

Compared to the huge need in Victoria, these 152 units are a drop in the ocean. Nonetheless, here, architects, government agencies and a private non-profit company have worked together to provide hope and opportunity. Edney describes it as “affirming low-income people.”

Credits

- Project

- Atherton Gardens Social Housing + Hub Development

- Architect

- Bird de la Coeur Architects

Southbank, Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Michael McCabe, Vanessa Bird, Neil de la Coeur, Glen Blamey, Vukan Misic, Nick Webb, James Parker, Celia Johnston, Claire Plumridge, Lauren Tyrrell

- Architect

- McCabe Architects

Collingwood, Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Builder

Abi Group

Cost consultant Napier and Blakely

Fire consultant JBA Consulting engineers

Interior consultant Artillery Melbourne

Interiors Woodhead

Landscaping Formium

Mechanical and electrical consultant JBA Consulting engineers

Structural engineer Robert Bird Group

Traffic consultant GTA Consultants

- Site Details

-

Location

Fitzroy,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type Apartments, Multi-residential

Source

Project

Published online: 7 Oct 2013

Words:

Justine Clark

Images:

John Gollings

Issue

Architecture Australia, July 2013