In 1999 grazier David Elliott stumbled over a large fossilized bone on his property near the outback town of Winton, in central western Queensland’s “dinosaur triangle.” The bone belonged to a twenty-metre-long, four-legged dinosaur that lived more than ninety-five million years ago. The discovery was proclaimed as Australia’s largest sauropod find. After unearthing hundreds more fossils, David and Judy Elliott lobbied for funding to establish a museum near Winton to display the dinosaur bones. State and federal governments and the local council all chipped in and the architect and building contractor worked pro bono on the first phase of the building program, the reception centre for the museum.

A local landowner gifted the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum of Natural History a mesa or “jump-up.” This dramatic, flat-topped outcrop of land rises steeply out of the extended plain, a commanding site. On top of the jump-up, the Elliotts first put up a big tin shed to serve as a workshop where tons of fossils being unearthed in the Winton region are cleaned, sorted and stored. The area has yielded the world’s largest collection of dinosaur bones. Next they planned for this small interpretive reception centre that has been built five hundred metres from the workshop.

The Elliotts heard about an architect in Brisbane. It would be longer than a year before Cox Rayner took on the project, but when the architects did become involved, they were won over by the Elliotts’ enthusiasm and knowledge.

The building has an amphitheatre, shop and cafe.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

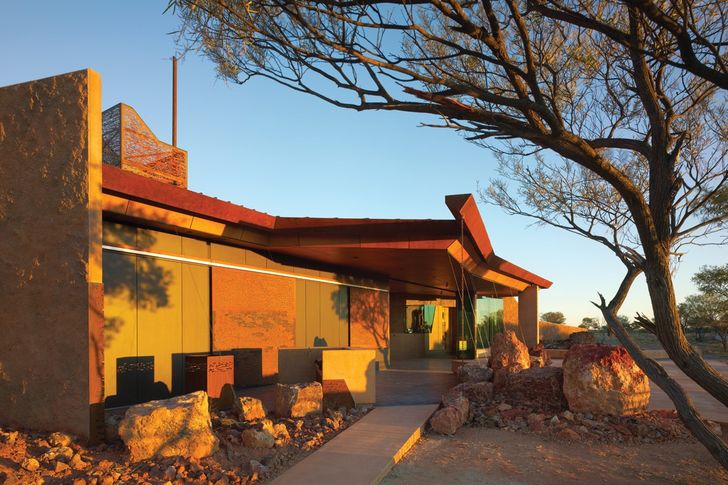

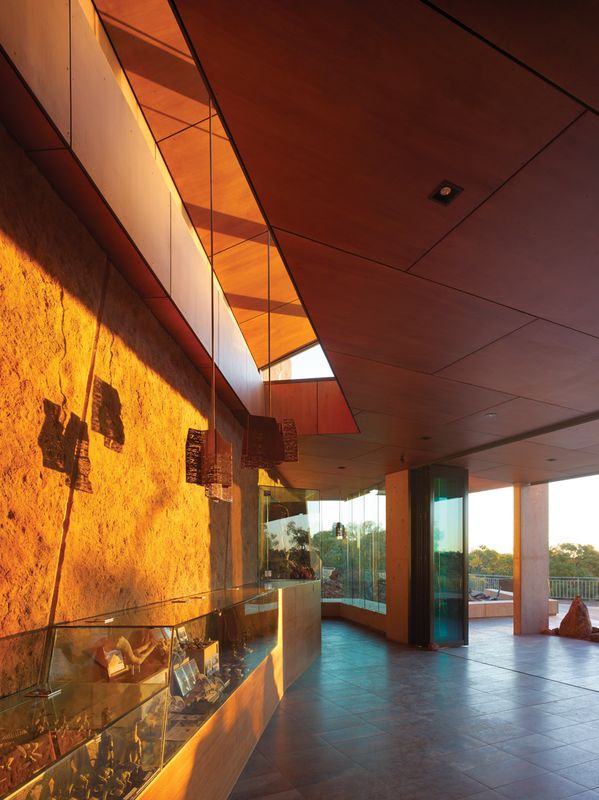

The reception centre is the first stage of a building program to display and interpret the dinosaur finds. The building contains a small amphitheatre, shop and cafe. Perched on the brink of the jump-up, it enjoys a sweeping vista of the open plain below. Visitors drive twenty kilometres from Winton, negotiate the winding dirt road up the side of the jump-up, two hundred metres above the plain, and then experience the sudden thrill of the grand elevated view of the landscape.

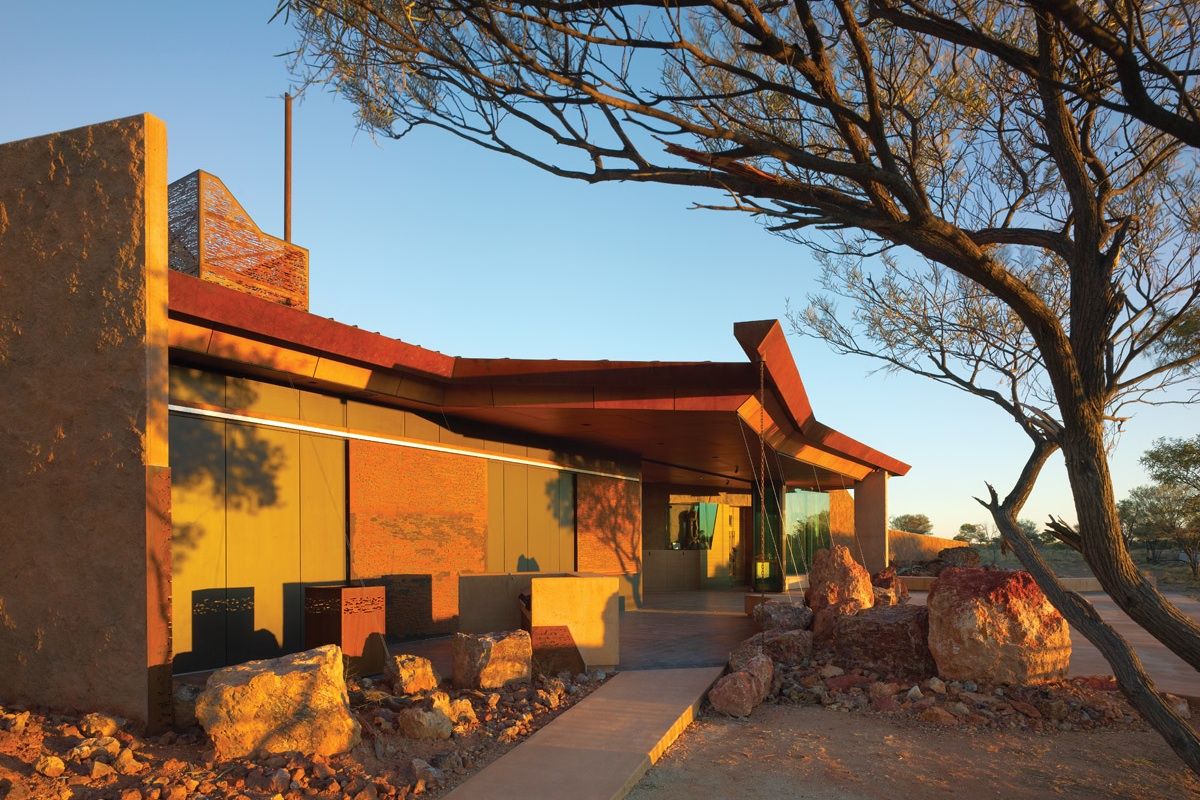

The rust-red building rises out of the mesa rock like an earthen extrusion. The immediate vicinity is littered with iron-streaked stones and boulders. Tapering, angled walls invite visitors along a promenade architecturale from the dirt car park to the narrow entry, where the plan is pinched and the building pivots. The doorway funnels the prevailing south-easterly breeze. Inside is cool. The timber ceiling and dark floor create the ambience of a cave; the eye finds immediate relief from the hot glare. Beyond the reception area, one side of the building opens to sunlight, the surprise of the view and the experience of being on top of the mesa. The architectural promenade continues past the shop area and channels visitors along a timber ramp into the timber-lined amphitheatre displaying the original fossils found by the Elliotts.

The front door is made from rusty steel, tough like the country. The door handle – and other door handles encountered – is a jagged slash of steel lashed with a soft rawhide binding. The leather is a mute reminder that cattle graze on country where the dinosaurs once roamed; also, it exemplifies the pragmatic skills that lift utilitarian materials – concrete and rusted mild steel – to an aesthetic level. This is a leitmotif of the architecture: the transformation of industrial materials through handcrafted intervention.

Tough materials are used in the detailing of the building.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

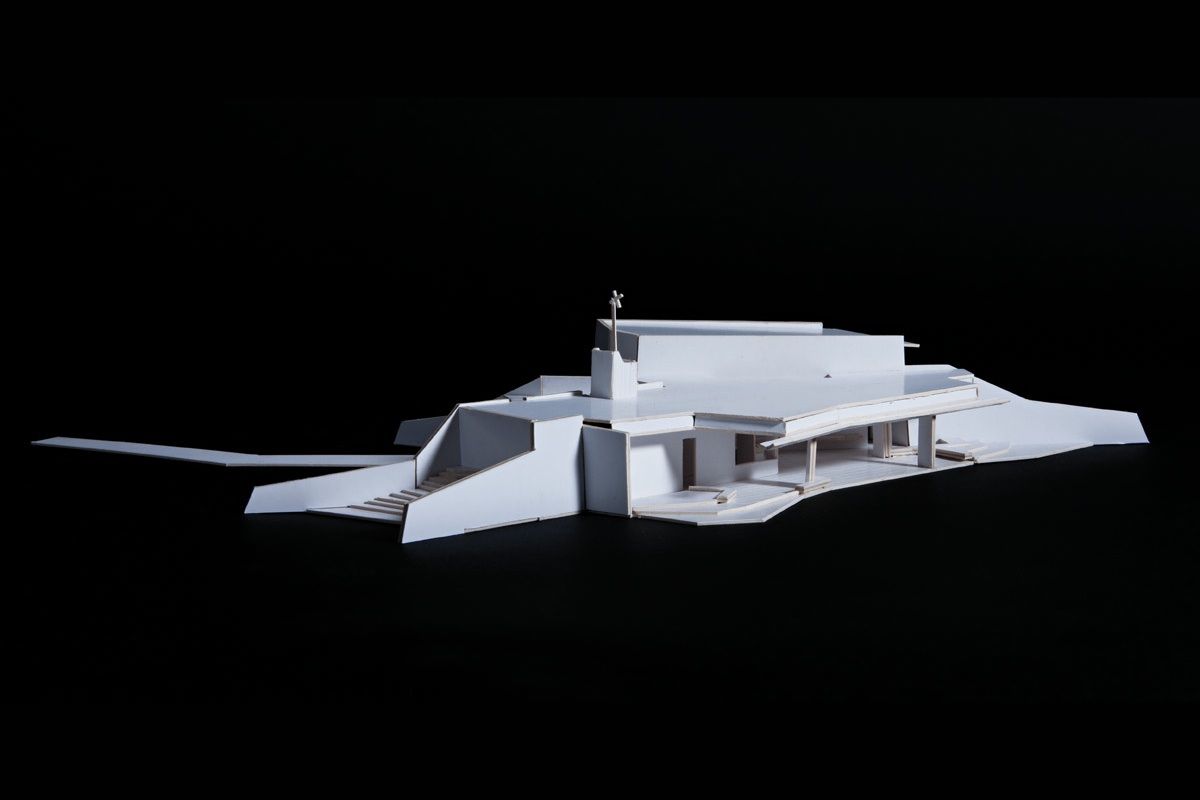

The sharp angles of the reception centre were inspired by the vivid terrain and the imaginative drama of what it contains. The building gathers up its skirts from the dust and twists skywards, culminating in a tall stack (concealing the water cistern) made of rusted steel incised with an intricate pattern hand-cut with an oxyacetylene torch.

The architecture is one of mass expression rooted in place. The boulders around the base of the building, from which the structure appears to grow, are artfully placed and contribute to the architectural expression. Beneath the boulders is a layer of mud-rock gravel that prevents water penetration to the exterior walls when it rains (annual rainfall is four hundred millimetres).

The Elliott family was involved in all aspects of construction, using outback ingenuity and machinery straight out of the farm shed. They carried out the excavations. An opal miner drilled footings into the solid rock. Services were cut into rock trenches. The freestanding wall panels were sat on concrete pads and braced. Structural steel was bolted into position.

The finished tilt-slab wall panels.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

The tilt-slab walls were poured on site, panel by panel, to ensure all the angles fit snugly. The Elliotts devised a special method to create a memory of rock on the surface of the concrete. They made latex casts of the exposed mesa bedrock. The latex mats were placed onto the poured concrete and stamped into the wet surface to imprint fissures and other rock markings. After the mats were removed, buckets of oxides – red, brown and black – were thrown across the cappuccino-toned concrete base and trowelled in to achieve random effects. Each slab is different. The Elliotts became adept at replicating the texture and colours of rock in concrete and they had plenty of practice, as the engineer condemned the first thirty-nine of the panels, which had to be recast.

The construction system is based on concrete tilt-slab technology developed in the US in the early twentieth century. Although Rudolph Schindler used tilt-slab construction in 1922 for his own highly experimental Kings Road house in Los Angeles, it never really enjoyed aesthetic currency among later designers. In the US, as in Australia, this technology is now widely (and almost exclusively) used for the construction of low-cost industrial sheds. Typically, the precast panels are fabricated on adjustable horizontal casting beds and craned into position. The technology is expedient. Casting imperfections and holes left by formwork fixings and lifting points are roughly grouted over. For buildings with pretensions to style, the panels are usually tricked-up with a coating of textured paint in an attempt to conceal their crude concrete origins. But here Cox Rayner manipulates inventive form-making and an artisanal approach to the material to promote tilt-slab construction to an architectural aesthetic.

Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum is shortlisted at the 2013 World Architecture Festival.

Credits

- Project

- Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum

- Architect

- Cox Rayner Architects

Brisbane, Qld, Australia

- Project Team

- Michael Rayner, Casey Vallance, Justin Bennett

- Consultants

-

Builder

Woollam Constructions

Certification consultant Philip Chun & Associates

Electrical & hydraulic engineer Cushway Blackford Consulting Engineers

Mechanical engineer AE Smith

Quantity surveyor Donald Cant Watts Corke

Structural engineer Bligh Tanner

Surveyor Hoffmann Surveyors

- Site Details

-

Location

Winton,

Qld,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Public / cultural

Type Museums, Visitor centres

Source

Project

Published online: 9 Jul 2013

Words:

Haig Beck,

Jackie Cooper

Images:

Christopher Frederick Jones,

Supplied

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2013