It is not often that one hears a post-occupancy client comment that a building is “perfect … there’s nothing that could have been better”. It is even more rare (and refreshing) to hear a work of serious, erudite architecture described as “a ripper”. These are the words of Dr David Middleton, senior vet at Melbourne’s Healesville Sanctuary, about the new Australian Wildlife Health Centre (AWHC) by Minifie Nixon. The AWHC is Minifie Nixon’s second public building after the much-discussed Centre for Ideas at the Victorian College of the Arts.

Middleton, who was the driving force behind what he believes to be the first open veterinary hospital in the world, is clearly thrilled with the building. His idea was to turn a traditional veterinary hospital literally inside out, exposing all of the procedures and operations that would usually happen behind closed doors. This programme and its spatial elaboration were developed over time, in close collaboration with the architects, and Paul Minifie notes that zoo staff were unwavering in their ambition and belief in what architecture can do. In return, on a programmatic level, they have received a very well planned, practical, modest and clever building. On a formal level, meanwhile, they have received a very odd beast indeed.

Zoos today have reinvented themselves. No longer is it the humans who are protected from the dangerous creatures behind bars: we, the gawking hordes, are now recognized as the true threat. This is particularly evident at Melbourne’s Healesville Sanctuary, which in its very name outlines the precarious position of Australia’s indigenous fauna in the wild, threatened from every side by loss of habitat, feral predators, and the daily carnage wreaked by cars. This last aspect is emphasized at the AWHC by a large faux street sign warning “Beware! Humans!” The facility acts as the hospital for the sanctuary’s permanent inhabitants, but it also has an important role as a centre where injured wildlife, brought in by members of the public, is received, treated, rehabilitated and ultimately prepared for release again.

The visitor first enters a main gallery, a doughnut of space with a glass-enclosed courtyard in the centre, and the outer wall slightly deformed into a bulging “apse” behind the reception desk.

Here the visitor is placed immediately in the midst of the action, with a series of glass walled rooms bordering this space – an operating theatre, laboratory, examination room and recovery areas are all directly visible, while a necropsy is accessible but protected behind a screen. This arrangement means that a vet in the laboratory identifying a pathogen can speak directly to the people watching outside, just as visitors can observe operations, live and close up, and even witness post-mortem dissections. When we visited, a vet and two nurses were operating on a kookaburra, inserting a steel pin into its broken wing. It was an amazing thing to see, with the X-ray of the broken wing visible on a lightbox and the anaesthetized bird laid out on the table, no more than a metre away from us. It is through authentic experiences such as this, it is hoped, that visitors will gain a sense of the connectedness of all animal and human life, extending to an increased sense of responsibility for wildlife in the wider world.

Interpretative displays by Cunningham Martyn line the centre’s main space, and these are effective, interesting and well conceived. The workspace and research library at the rear of the building are generous and well lit, and apparently pleasant places to work.

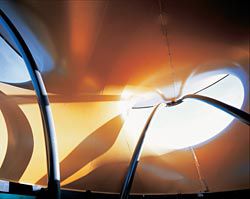

But the real architectural action is on the facade and in the main gallery above eye level, where the ceiling is a startling surface of continuous compound curves, gold fabric swooping upward into a series of funnel-like orifices. This element is in fact a formalized mathematical concept known as a “Costa surface”, a “complete minimal embeddable surface of finite topology”. Its use here is part of the architects’ ongoing interest in design technique, and in bringing maths and architecture into the close adjacency they enjoyed in earlier centuries. But while the association was historically about beauty, proportion and order, in the AWHC mathematical geometry is used to a different end altogether.

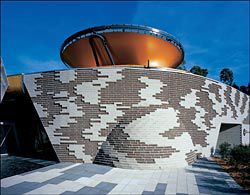

There is also a level of mimesis in the AWHC, and it is of a curious type. It is not a zoomorphic mimicry of a creature in finished form, such as can be found at Gregory Burgess’s World of the Platypus, also at Healesville, with its platypus reference in plan. It is rather a mimicry of the more fundamental organic processes that produce all life, filtered through and modified by digital technology. This is most evident in the vaguely gecko-like mottled stripes of the AWHC facade, where the architects used a “cellular automaton” algorithm which, when plugged into the computer and set in motion, “designed” the blockwork pattern. In generating the pattern, the computational process also “knew” where programmatic building elements – doors, windows and so on – were located, and transformed the pattern in response. Minifie states that the intention here was “not a cold mathematical or experimental exercise,” and sure enough the resulting pattern chimes very well with the building programme. It opens itself to metaphor without pastiche, it expresses both artifice and the organic, and it suits the scale and pretensions of the building. It also seems to avoid some of the potential pitfalls of this kind of design approach, namely that it can result in a coy retreat, a refusal to admit the actual role of aesthetic judgment, a false and disingenuous abandonment of authorship and “design” as such.

But while this process works well in the facade, it is less convincing in the Costa surface which, by its nature, cannot be adapted – it is a self-contained and self-fulfilling form.

The interest and pleasure in appropriating such forms in architecture seems to lie in the inventiveness of working out how to use them – here we have this fixed complex form, now how big should we make it and what can we do with it? But there is a danger in this approach – that the appropriated element can be both conceptually and formally out of sync with the rest of the building.

It seems to me that this is the case here: the gold element is bewildering in its incongruity, especially within what is otherwise a very coherent building.

It is clearly far more than a solar chimney or skylight, and while it draws attention to itself as though it had a representational function (its height and colour alludes to cupolas, Minifie explains), it is very difficult to work out what that would be.

Its spatial high jinks work well internally: the effort of puzzling out the geometry and construction, the appreciation of the vertical interpenetration of internal and external space, and the peculiar effects of light and air in the central courtyard are all curious, novel and pleasing. But externally, to my eye, the gold eruption above the parapet is perplexing.

In thinking and writing about this part of the building I have swung between extremes: between admiring the scholarliness and consistent experimental daring of the architects; feeling exasperated at what seems an intensely idiosyncratic (not to say peculiar and arcane) exploration of concerns which have nothing to do with this programme or client; appreciating the logic of the gold element as an expression of hierarchy within a flat disposition of programme (the whole thing can be read as a kind of perverse Stockholm Library); feeling a simultaneous distaste and fascination for the gold thing’s aesthetic and materiality, while also being amused by the architects’ willingness to redeem tensile fabric surfaces from their “hideously abject” (in Minifie’s words) association with service station canopies; and pondering the place of all this in the venerable tradition of the architectural folly.

Ultimately, the simple reality is that the activities going on inside the building are so fascinating, and so well served by the architecture, that the more inexplicable or impenetrable aspects of the “content” will remain unremarked on by its occupants and the lay public. Meanwhile we architects will continue with our abstruse disciplinary debates, which is surely the point.

The complex and contradictory reactions that this building will generate in its architectural audiences are surely one of the project’s great strengths.

As the fulfilment of a complex brief, the building is a resounding success. As an example of the architectural process helping to explore and expand a new kind of programme, and of the architect as a facilitator and agent in this process, it is impressive.

As a formal outcome, while new, strange and interesting, it is not always so immediately satisfying. But if a building can juggle, sing and ride a unicycle at the same time, it seems churlish to complain if it drops the occasional baton.

Technique and the AWHC

In our work we find it useful to explicitly consider design techniques, as it is around techniques that the other stuff of architecture organizes itself. Design techniques establish a domain of possibility in which a building comes to be, and to be apprehended.

A technique can be understood as something that defines the properties of elements, their qualities and the relations they can enter into.

These elements need not be material things, but, to make sense in an architectural context, they must be able to have a material instantiation.

A building can be understood as one of many possibilities consistent with a given design domain (think of the vast populace of the Miesian domain). Many of the significant architectural values of a project come about through specific decisions made within the parameters of the design space – decisions about composition, materials and so on establish emphasis and value. Some of these aspects may be addressed in the main critical text. Here the focus is on the techniques.

The Costa surface is a “complete minimal embeddable surface of finite topology”. It is an element that has the smallest surface area for its constraints, could continue without boundary and does not intersect itself. Until this surface was discovered by Costa in 1984, the only other known surfaces with these properties were the plane, the helicoid and the catenoid – all three well known to architecture. The Costa surface was discovered through “experimental mathematics”, whereby computers are used to investigate a large number of cases prior to deriving formal proofs. Such surfaces cannot be known directly; they require a computational process which iteratively finds a final form from a set of constraints. This mode of working – finding a resolution of “embodied forces” – places the designer in a different relation to the building than that of “wilful formmaker”.

Similarly, the “embodied forces” are available to be apprehended by those experiencing the building. At the AWHC the Costa surface element is resolved to form the roof, courtyard, skylights and solar chimney to the public areas.

A cellular automaton is a collection of “coloured” cells on a grid of a specified shape, which evolves through a number of discrete time steps according to a set of rules based on the states of neighbouring cells. Cellular automata were studied in the early 1950s as a possible model for biological systems. The particular rules used at the AWHC are a weighted sum of the regions surrounding a given cell and applied to an initially random seeding.

The sequence always converges to a stable pattern, which is expressed as a masonry setout.

The horizontal or vertical components of the rules are weighted according to the proximity of various building elements, allowing the building skin to respond to both expressive requirements and building programme.

Paul Minifie

Credits

- Project

- Australian Wildlife Health Centre

- None

-

Minifie Nixon

- Project Team

- Ellen Yap, Sam Rice, Fiona Nixon, Barend Meyer, Paul Minifie, Nicholas Hubicki, Brandon Heng, Matthew Herbert

- Consultants

-

Builder

Behmer and Wright

Building surveyor Philip Chun & Associates

Interpretive consultant Cunningham Martyn Design

Landscape Healesville Sanctuary Works, Horticultural Departments. Client Zoos Victoria, Healesville Sanctuary

Landscape architect Rush\Wright Associates

Project manager Root Projects

Quantity surveyor WT Partnership

Services consultant Irwinconsult

Specification Davis Langdon

Structural consultant AHW

Tensile engineer Tattersalls

- Site Details

-

Location

Healesville,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Type Conservation, Public / civic