Foreword

Lawrence Nield, 2012 Institute Gold Medallist.

My Gold Medal lectures are concerned with two apparently unrelated issues – on one side architecture and its material substance, and on the other architectural specialization. By re-materializing I suggest we can move away from the architecture of pure form (which is a dangerous waste of materials). Useful specialization and its associated research on the many facets of performance may also drag us away from the seductions of pure form. For example, the Beijing “Bird’s Nest” stadium has almost as much steel as the Sydney Harbour Bridge. This is substance abuse.

Architecture

Architecture is the framing of the lives of people and the lives of materials in response to situation and circumstance.

This is my working definition that I have used in practice and teaching for many years. I am insistent that we should see materials as having “lives.” Wood communicates the growing trees, the milling of the timber, the skill of the carpenter, the grain of time. Steel communicates by careful jointing. Good bricks signal the careful firing of the selected clay, the subtleties of salt glazing, the skill of the bricklayer, and the capacity to develop a patina over time. Materials have personal, physical and energy lives. Personal involves their origin, touch and crafting; physical the movement, weathering and physical properties such as hardness, thermal performance, etc.; energy is the lifetime carbon footprint.

Five techniques

The way we deal with the lives of materials is, or should be, a central craft of architecture. Just appreciating the significance of materials is not sufficient. We must know how to use them – the trade and craft of the assembly. Like sculpting, carving and modelling are central techniques. Adrian Stokes greatly expanded this description of art by introducing and revealing the impact of “carving” and “modelling.” Carving and modelling are also, I consider, clearly important – but differing – techniques in architecture. I am not sure why this simple distinction, which has such a powerful visual effect, is not considered in our design. To carving and modelling I add three other fundamental techniques: casting, opening and standing.

Carving

Carving is reductive, giving the appearance of coming from a bigger “endless” lump of timber or stone. Again and again we seek to unify an assembly of components, by deep reveals, by secret jointing, by mitre cutting, by cover-moulds and moulding, by rendering and painting. We want to communicate “wholeness”; to make it appear as though the building is carved from one enormous block.

Modelling

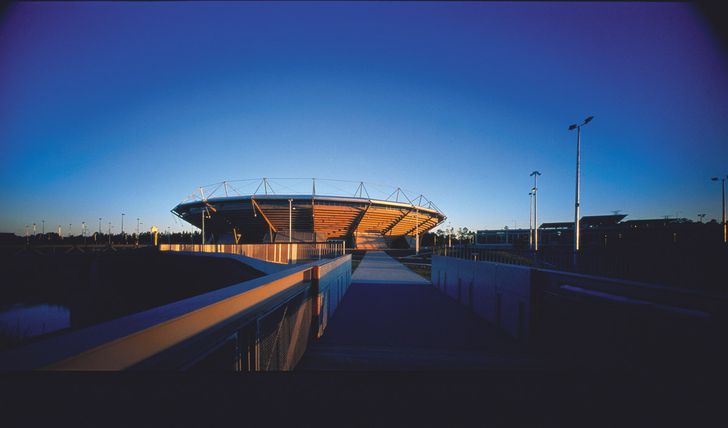

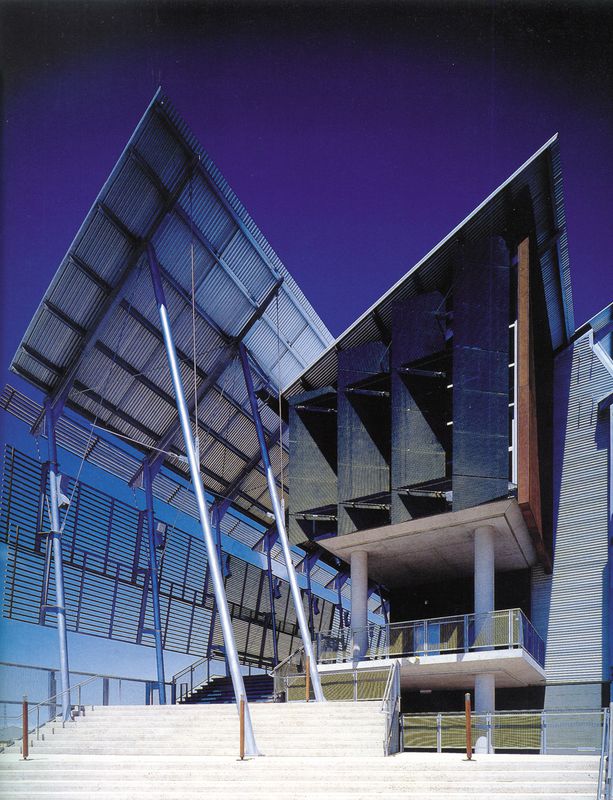

Modelling: Sydney International Tennis Centre (1999).

Image: Anthony Browell

Modelling is additive: in sculpture clay is added to clay, in architecture brick is added to brick, tile rests apparently on tile, or panel is connected to panel. Jointing is expressed and celebrated. In building, modelling allows ambiguous figure-ground readings of the constructive assembly. Modelling draws the eye in.

Casting

The third common process is casting. Cast concrete can look like a petrified timber frame or a massive dam wall. Formworkers are bad carpenters. Particularly with in situ concrete we see the petrified imprint and remember the lost formwork with its human mistakes. But, in contrast, precast can be a wonderfully precise element, like a metal casting.

Opening

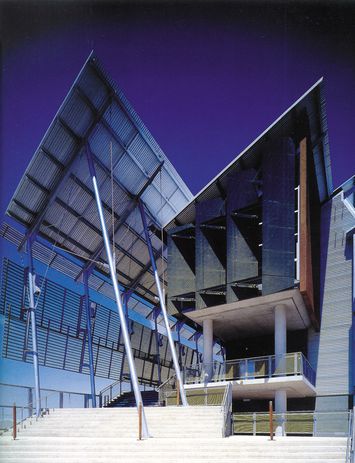

Opening: Sunshine Coast University Library (1997).

Image: Anthony Browell

The fourth, very significant technique is “opening,” which is the making and ordering of aperture, emptiness, porosity and transparency. Nothing gives life to fabric and buildings more than apertures, porosity and transparency. It obviously includes “window,” but is far more than “window.” Apertures allow connection to, and understandings of, air and wind. They make darkness and light. Openings proclaim a story of habitation. The complex manipulation of “opening” is a critical technique.

Standing

Standing is my fifth technique and perhaps the most difficult to understand and to craft. “We transcribe architecture into terms of ourselves” (Geoffrey Scott). Standing is the technique concerned with somatically conveying balance and stability in the object architecture, and at the same time about standing alone or together, about being part of a family (or not), thus it is about scale. We see and, importantly feel, if architecture is not plumb and balanced, or not part of a family standing together. A city is buildings standing together.

Why are the “strength” of materials and the five techniques important? I suggest by focusing on materials we can move architecture away from the architecture of pure form, of the cults of personality and of “starchitects.” I have written at length in my lectures about the ten tendencies, from Iconic One-liners to Neo-Nudge! Nudge Wink Wink. Design became the preserve of style leaders. The new freedoms won by the modern movement have resulted in architecture of narcissism making autistic cities or “soapy” suburbia.

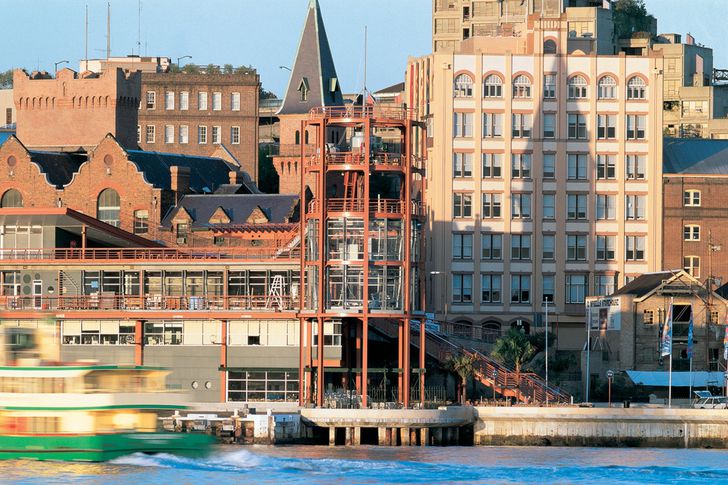

Carving/Modelling/Opening: Overseas Passenger Terminal at Circular Quay, Sydney (1988).

Image: John Gollings

I mention here only one of the more distressing of the ten tendencies – the Zombie building. Zombie buildings are usually glossy and glassy with frit, tint and colour-backed glass or “wild abstract” pattern-making. But where are the people of the building? Is there anyone home?

Specialization

Building is too important to leave to the narcissists, the corporate offices, the government legislators or planners, the engineers, the project managers and the builders. It will cost too much in carbon dioxide. It will be too costly to our planet. Not unrelated is the fact that architectural courses (I say this as an academic) produce general practitioners.

Alan Short has called for greater specialization. “It is difficult to get real accounts of buildings and how they perform.” Architects are all about intellectual property rights, legal claims cultures and fee margins. Don’t I know! The profession Short says has no top end. There are plenty of “starchitects” but no famous professors or specialists “to act as the cross over between a profession representing the vested interest of architects and client and important objectified academic research that is beholden to neither.” Furthermore, the big offices do not share their specialist design skills and data because it is “commercial-in-confidence.” It allows them to win the big, complex jobs.

I believe we, the profession, should follow medicine more closely and develop colleges of specialization based on practice. In medicine, we have the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons or the Royal Australasian College of Physicians. The colleges in medicine develop specialities, set standards, admit members based on examinations and develop research. Ever since William Osler and Abraham Flexner’s revolution, US medicine teaching and specialization has been based on practice – on learning with senior doctors and patients in the clinical setting, not learning through lectures. In The Flexner Report (1910) Abraham Flexner stated or restated that medical graduates should:

- relieve suffering

- add to the pool of knowledge and

- be prepared to teach in the clinical setting.

Architectural graduates are expected to relieve suffering (to put design in a negative way) but not to add to the pool of knowledge or teach in a practical setting. I think they should. I propose three basic specialty colleges for architecture based on the practical and timeless triad of our project work – design, documentation and construction. I suggest:

A college of design and sustainability might have the following divisions:

- advanced sustainable design with landscape

- conservation and heritage (which I think is already a specialty)

- urban architecture and design, including infrastructure and street design

- efficient land use, built form and sustainability

- multiple residential building

- specialist architecture – hospitals, transport, sport.

A college of architectural production might include:

- computer design techniques

- detailed sustainable design and

data bank - CAD and visualization

- BIM and intra-operability

- project data banks and their access

- real quality assurance.

A college of construction might have the following sub-specialty divisions:

- procurement, contracts and supply chains

- site communication and information technology

- waste, salvage and energy-efficient construction

- site observation and monitoring techniques

- compliance and quality assurance

- advanced construction and contractors data bank.

It seems logical that research and specialization should relate and be useful to the making of buildings. More than 80 percent of current university research in architecture schools is useless because it is not related to practice. It is difficult, if not impossible, to get real accounts of buildings (and cities) and how they perform. I suggest objectified research needs to be developed, retained and propagated though the three proposed colleges.

Following the doctors’ model, there could, of course, be Australian and New Zealand colleges, or even better, Australian, New Zealand and Hong Kong colleges in this Chinese century. The colleges I suggest should be initiated and controlled by these two or three institutes until they become self-supporting. The learned colleges would have centralized banks of information available to all their members.

Afterword

In this forum there is not enough space to convey in more detail why the use of materials is so crucial to architecture now, and to my architecture. A partial, illustrated account can be found here and in Architecture Australia, March/April 2011. A complete text is now on the Australian Institute of Architects website.

As architecture gets more and more complicated with increasingly complex building tasks and sustainability it is important that this profession gives leadership to the industry through both heart-stopping design and specialized knowledge.

With limited space, I cannot appropriately thank the many colleagues who have walked with me down the long paddock. Always, though, I must greatly acknowledge and thank Andrea. She is my wife, my muse, my critic and the greatest of architectural partners. I must thank our boys for putting up with me. I must also record my great appreciation of my partners and colleague architects at Bligh Voller Nield and Lawrence Nield and Partners. My profound thanks to the Australian Institute of Architects again for the 2012 Gold Medal and to the many people who attended my lectures across Australia. I will continue to give architecture my all.

Source

Discussion

Published online: 1 Jan 2013

Words:

Lawrence Nield

Images:

Anthony Browell,

John Gollings

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2013