On a remote shore near Tathra on the NSW south coast, surrounded by melaleucas and spotted gums and set in a shining carpet of budawangs, Graeme Gunn’s 1968 Baronda House surprises on many levels. The first and greatest is that a work which so powerfully distils the spirit of the 1960s should be so little known. The second is that it is so passionately adventurous, the pinnacle of commitment by client, architect and builder. There are many surprises too in its spiralling pinwheel of spaces, its opening and closing to that magic landscape, its ability to house comfortably a couple or a crowd.

The client, David Yencken, has a long history of involvement in public life and culture. Graeme was one of a series of leading Melbourne architects commissioned by David for his progressive project home initiative, Merchant Builders, which, along with Sydney’s Pettit and Sevitt, led the affordable, architect-designed project home movement of the late 60s and early 70s.

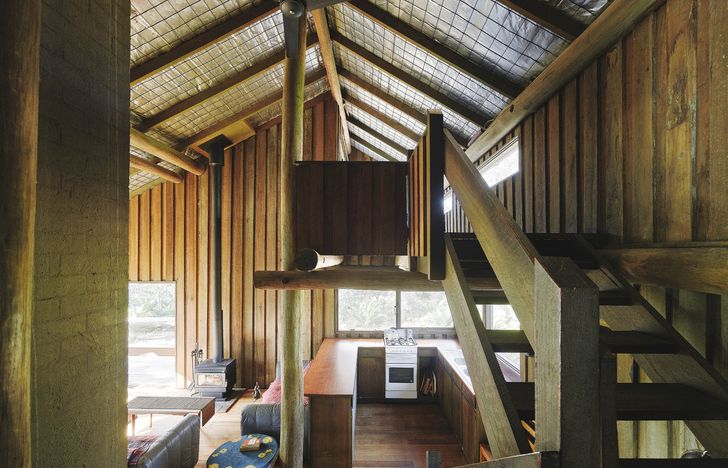

The house is composed of nine-foot modules defined by the framework of massive, round tree trunks.

Image: Peter Bennetts

The construction of the house followed David’s commissioning of that quintessentially Melbourne architect, Robin Boyd, to design one of the earliest motels in Australia in nearby Merimbula. The Black Dolphin is a masterful, Japanese-inspired composition of black lacquered and raw timber. Following the Black Dolphin, David flew over the coast to find a remote, untouched parcel for a weekender. He negotiated for the purchase of the thirty-hectare site, nestled on an estuary near a surf beach, with virgin bush for miles around. To the north, similarly large parcels had been bought by two other Melbourne identities - Robin’s former partner Roy Grounds and the retailer Ken Myer. The two had jointly set up a timber milling and preservative treatment plant, Penders, as well as constructing an iconic series of rural houses and sheds.

The brief was for a simple two-bedroom house with the capacity to accommodate much larger groups in a sleep-out. After considerable “sweat,” Graeme reached the design relatively quickly, producing sketches of a complex but resolved spiral of spaces reaching out to the landscape from a firm masonry core. While considerably larger than the brief, the design captivated the client - in David’s words, “It had to be built!” - and the work proceeded. Using treated spotted gum logs from the Penders plant for columns and beams, the house was to be entirely finished in locally sourced sawn stringy-bark, excepting only the great brick chimney at its core and the corrugated roof.

Internally the spaces flow naturally into each other.

Image: Peter Bennetts

The builder, a carefully selected local, undertook the project as a lump sum, working from a wooden model built by Graeme. The initial idea was to use only canvas for the walls and windows to save money. The local council objected and the house was finished almost exactly as it is seen now.

The house is like an occupiable construction toy - a complete vertical and horizontal grid of nine-foot modules defined by the framework of massive, round tree trunks. Each level of the house rises a half module - four feet, six inches - above the last, creating a complex spiral of spaces climbing around the brick core. The design thus reflects one of the obsessions of the period, where module and repetition were central to the intellectual and practical manipulation of material into architecture. This machine-like layer of standardization was seen to smooth over the handcrafted nature of building with a more contemporary suggestion of mass production. The composition can be likened to a systematized Fallingwater crossed with a log cabin rising from a level site in the bush. It is just as daringly cantilevered and nearly as complex spatially. And like Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, it succeeds in the difficult design task of enlargement - a small house grown in scale and apparent size by the included architectural journey, by the complexity of interlocking volume and by the variation of prospect and light.

In a landscape of melaleucas and spotted gums, on a carpet of budawangs, the Baronda House is an icon of the late 60s.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Its minimalism of material is a further defining character. There are really only three materials, internally and externally: the Australian hardwood, the unpainted bagged brick and the “Super 6” fibre cement roof. The timber walls and muscular poles create a series of living spaces, indoor and outdoor, modest in size but generous in character, each with its unique volume, each at a different level, each facing a new part of the surrounding landscape. They range from an enclosed lock-up “pantry” (sanctuary against theft in this remote location) to a couple of bedrooms (one lavishly large, one tiny), a narrow loft for the kids and, in the middle, the tall volume of the living room opening out to the northern deck. Small by today’s mega-everything standards, it is a place of luxury due to its setting and the richness of its architecture.

The house at Baronda Head is a kind of icon of the late 60s, with its progressive structuralist form, flowing spaces and machine-like diagram, as well as its pioneering environmental self-sufficiency. But that’s not the full story, and the subsequent history of the site further illuminates the progressive and sustainable ideals of its period and its creators.

The tall volume of the living room opens out onto the northern deck.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Sensing the growing development pressures on this wonderful coastline, the owners teamed up with those of the nearby compounds and, in 1979, gifted the land to the NSW National Parks - on the condition that a much larger terrain be included. The house is thus an architectural symbol of the wider, and far more significant, effort of a few enlightened individuals in establishing the 5,800-hectare Mimosa Rocks National Park. It is an appropriate symbol, in that it has literally grown from its site, using the timber from the land, processed locally. Graeme says, “If there had been rock it would have been made of rock,” but this is hard to imagine.

The house, now owned by National Parks, is still used by its creators under licence, but its future as a national asset seems somewhat doubtful. It needs a loving owner committed to its maintenance and deserves our protection as a major work of Australian culture.

Credits

- Project

- Baronda House

- Architect

- Graeme Gunn Architects

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Graeme Gunn, Herb Greenwood

- Site Details

-

Location

Nelson Inlet,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Source

Project

Published online: 1 Dec 2010

Words:

Peter Tonkin

Images:

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Houses, December 2010