<b>REVIEW</b> MICHAEL TAWA <b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> PATRICK BINGHAM-HALL

Review

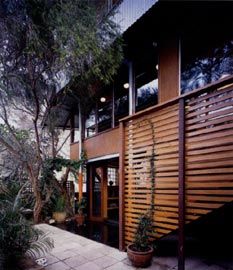

Detail of the north elevation, with studio below and living area above.

East elevation.

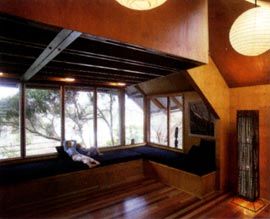

Looking north-east over Balmain backyards to the city, framed by the broad brim of the roof in the upper level main bedroom.

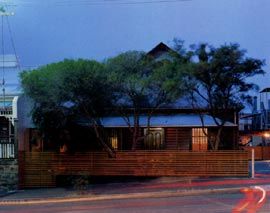

West street elevation.

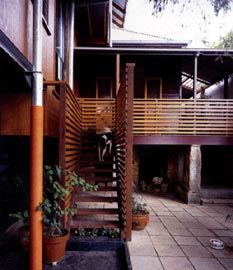

Oblique view of the north elevation, with the upper level projecting over the lower two, seen from the courtyard.

Looking towards the new verandah, designed by Bruce Eeles and Associates, with the existing cottage beyond.

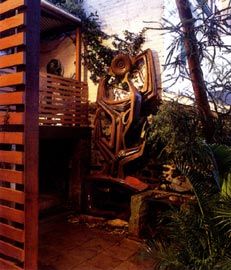

Sculpture by Tom Bass – rescued from the AGC Building, Phillip Street, Sydney – in the north-west corner of the courtyard.

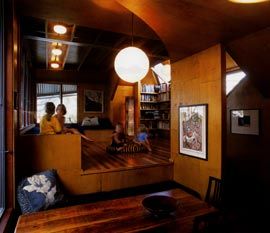

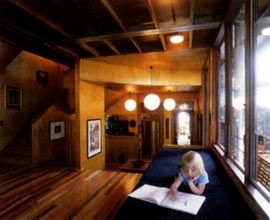

Looking across the dining area into the living areas.

Dining and kitchen seen from the living area, with the entry verandah seen through the windows to the right.

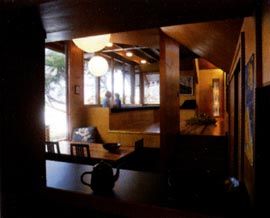

The dining and living areas framed from the kitchen.

The north-east corner of the living room, wrapped with frameless windows.

Looking across the living and dining areas, and through to the hall of the existing cottage.

The plywood skin of the stair.

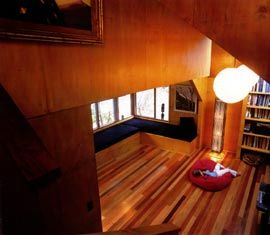

The new bedrooms housed in the roof space. Looking from the main bedroom along the hall to the chidren’s bedroom.

The view down the stairs into the living area, with its mixed hardwood floor.

IN THE SAME KEY. Rex Addison’s work is remarkable for a consistent reworking and elaboration of traditional and local house forms, geared to adapting new kinds of inhabitation which are tightly calibrated to place. The Balmain house, for Patrick and Katrina Bingham-Hall and family, extends these concerns – this time in the unfamiliar context of inner city Sydney. Beyond stylistic concerns and formal consistency, the work prompts important reflections on space, place and pedagogy.

The Bingham-Hall project is a modest, yet fairly complex little building, carefully built by Craig Lester on a tight budget. Addison has managed to increase threefold the area of the original timber cottage – largely due to a sloping site and steep pyramidal roof that allowed spaces to be tucked in below and above the main floor level, and, naturally, by judicious and very skilfully controlled design.

The extension is on three levels – a mid level extending the original cottage floor to a raised living space on the east; a recessed basement level with studio and darkroom; and an upper floor of bedrooms projecting beyond the lower floors. The cross section is typical of Addison’s work – playing frame against wall and screen, through bays receding from and projecting beyond the beams and columns of a trabeated structure.

The front screen, side deck and wraparound verandah had already been designed by Eeles Trelease Architects, but were built together with the Addison project. These elements have turned the northern wall of the existing cottage into a series of pillars – the internal floor continues beyond the wall to form a sheltered useable space adjoining the bedrooms. This verandah leads around to a relocated eastern entry. Here, kitchen, dining and raised living areas form a continuous space edged by bays and alcoves.

Closed and contained on the south, this space open and expands to the north-east through sashless windows wrapped around the corner. The splayed overhanging eastern wall of the bedroom above concatenates this diagonal tension, while the raised living area closes and holds the space back. Addison quietly modulates flow, containment and release by carefully scaling, stepping, closing and opening vistas. He also brings light in from above, washing the corner walls on the south-east, and the overhanging walls of the bedroom above. The whole appears to be a community or familial continuity of places. A sort of luminous clearing at the edge of a small sandstone scarp, with broad raised or tilted ledges for sitting, and a prospect that takes in fore, mid and background without losing any sense of proportion.

The new is anchored in the old and emerges from it, but not in the sense of an alien presence or prosthesis. It is mostly all roof – turned down on the south as a back to Darling Street, ridged and stepping out on the north and north-east. The new spaces are pocketed into the old roof in a kind of involution that also turns the cottage away from the street, towards the harbour. New is not inserted into old, or attached to it. Rather, it grows from inside out to elaborate intrinsic opportunities. The project’s inventiveness is not in formal concoction, but in the decoction or condensation of propensities always-alreadythere.

In Addison’s words, the cottage is not “monstered” by a hi-tech cube, as it might have been by the “Carbuncle School of Design”. Instead of asserting its individuality, the new works “in the same chord as the original” by “tuning into the same key”.%br% IMPERATIVE OF THE ORIGINAL. Quiet modulation. Careful scaling. It seems to be a matter of discipline – of knowing and respecting the rules well enough to play around with them, interpret them, and put them to the test. The skill comes with a working knowledge of the formal potential and tectonic patterns of gable, hip and valley roof geometries. In Addison’s buildings, volumetric complexities are developed entirely within a structural, constructional and geometrical logic, which he nevertheless tempers according to specific circumstances and local conditions. Above all, he is interested in the sheltering power of roof forms – the roof as cloak, instrument and gear – and in the play of spaces which advance and retreat, horizontally and vertically, within the volumes such roof forms envelop.

The pedagogical value of his work is that in it there is both discipline and improvisational freedom. The discipline is to accept and work with both the natural resistance and the propensities of this geometry – what Addison calls the “imperative of the original”. The given, the always-already-there, is both limit and opportunity. Design is not a premeditated imposition, but a going along with whatever presents itself within the logical possibilities of the given. It is also a question of maintaining a kind of counter-resistance, so that the circumstantial might weigh on the given, and prompt it to yield to other, surprising opportunities.

This rhythm of keeping to and departing from a system is playful – it is precisely design as play. But it is neither self-conscious nor a priori intentionality. Rather, practice as play and the playfulness of the outcome both arrive, as with musical improvisation, together with the performance. They are neither predicted nor predictable. Likewise, if the detailing is refined, it isn’t in the sense of having long been aestheticised as a formulaic practice also sought in advance of the work, but in and as the work itself, in a process of interminable reworking and refinement. In this sense the work escapes becoming a parody of itself, a cliché, a predictable style, a repeatable pattern. As with all mature work, each project is radically different and new, in the sense that it reworks and recasts the old through interminable variation and adaptation. And yet there is formal and stylistic continuity – like there is grain in a voice, or like Miles Davis might be unmistakable whether he is playing Doo-Bop or Kind of Blue. This unmistakability means a restricted palette – but one that is indefinitely deployed and deployable. As the Chinese have it, “to recall old things is better than to invent new ones; and to recut an ancient text is better than to engrave a modern”.1%br% THE SPACE OF FORESTS. With this project – largely because of site constraints that called for tight and predominantly vertical scale – Addison has managed to extend the spatial opportunities that have been available to him so far. Rather than horizontally layered sequences or rhythms of pitched beams and columns extending beyond walls into lush gardens, spaces here twist, turn, infiltrate and hover in and around solid volumes. There is a move from slatted battened screens and dappled light in Taringa, to roof and wall becoming ambiguous and folded into each other in Balmain. From forests where all is floor, column and canopy, to the inner surfaces of caverns. From trabeated frames to angled walls, smooth panelled coffered ceilings and the inside of boat hulls.

The interior is predominantly a taut silky skin, although there is also recurrent play between skin and bone, surface and line, cladding and frame. The gutter is separated from roof plane just enough allow us to see the sky skin the building, peeling it apart, exposing bone and brim. I saw it first in Asplund’s Woodland Crematorium Chapel, but here it seems to analogize the play of light through branches and foliage in rainforests.

Upstairs, the rooms are the roof, which is neither an erased nor lost space (as with skillion roofs) nor a space of dust and insulation but a place in its own right, places in their own right. From these places you look down – because the roof presses steeply to furrowed brow in some parts (the western bedroom), and opens up to broad brim in others (the eastern bedroom). Looking down and away through angled frames, or across lower skillions, is like looking down on one’s shoulders, or onto the edges of billowing coat tails, or like being perched high on Sclerophyll. The back of beyond is the backs of shops, yards and yards of bleached walls, rusted tin and clay tiles, vines gone wild and droopy gums, patched down the northern slope of the Darling Street spur. This is a real roofscape, gleaned from an inside that lends a glow to what it sees.

There are clearly metaphorical aspect to Addison’s work – nautical in the Endeavour Gallery of the James Cook Museum (2001); arboreal in Addison’s own house and studio (1998-9). There are clearly many possible interpretations, and many tales to tell. The more inventive the narrative, the better the set up. For me, Addison’s work – particularly this house – implies a concern for responding to more complex and non-Euclidean understandings of space – spaces of torsion, of multiple and simultaneous viewpoints, of ambiguous boundaries. Space is experienced in moving about, not surveyed from a static point.Working with the language of traditional roofs – but also meddling with it to peel it back at the edges, to undo its seams, to tilt or fold wall into roof – allows Addison to organize faceted spaces of volumetric intricacy and dynamic potential. And not only internal space, but also the way the outside is framed. A simple example is the angled heads and sloping sills of the bedrooms on the first floor. These break any sense of perspectival survey or picturesque depiction of the outside, all of which come with the territory of plumb and level rectilinear frames, of monstrous cubes and carbuncles. The sense of space here is entirely other. I can’t help thinking of the painter William Robinson’s work – multiple points of view, multiple vanishing points, multiple time frames, space that flexes, ebbs and flows. In that sense, rainforest and Sydney topography are alike. Both resist the linear and the rectilinear. Addison’s work is no Corbusian poem to the right angle. Rather, it says something significant about the experience of dwelling amid folded terrain and the space of forests.

%br% 1. Cao Xueqin, The Story of the Stone, trans D. Hawkes (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1983), p. 328.

%br% %br% %br%

MICHAEL TAWA TEACHES ARCHITECTURE IN THE FACULTY OF THE BUILT ENVIRONMENT, UNIVERSITY OF NSW.

Project Credits

BINGHAM-HALL HOUSE, BALMAIN

Architect—design and documentation Rex Addison, Addison Associates; contract administration James Stockwell; deck Eeles Trelease Architects. Structural engineer Salmon McKeague Partnership—Mani Salmon.

Builder Customised Building Co—Craig Lester. Client Patrick and Katrina Bingham-Hall.