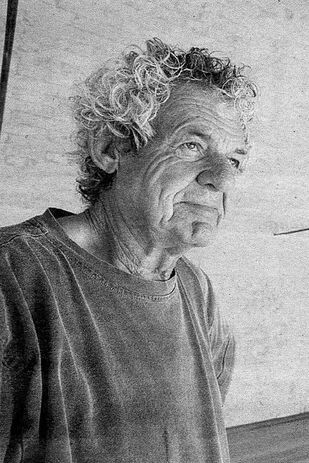

Brian Klopper.

Touch the earth lightly. If you live outside of Western Australia you may not have heard of architect Brian Klopper, but you will certainly have heard the Aboriginal expression used by a traditional custodian of the land during the infamous Hill 50 land rights/mining controversy in 1980. Klopper’s discussion of the expression with Glen Murcutt led to the term becoming entrenched in the architectural lexicon.

An exhibition of Klopper’s work, Brian Klopper Architectural Projects, was curated by Simon Anderson and Andrew Murray, at the Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts at the University of Western Australia, (UWA) from 19 March to 13 April 2012. It was the seventh in a series on Western Australian architects curated by UWA staff and students. The series is designed to both record and to bring significant local architects and practices before Western Australian architectural students and the public.

Klopper, a third-generation Australian born in 1937 in Northam, an early farming area of Perth, is something of an anomaly. An architect/builder/developer, his work, firstly in Subiaco and later in Fremantle, is largely single- and multi-residential. His projects, particularly the earlier ones, are simple and childlike: he relates this directly to the nineteenth-century farm buildings and mills of the country areas adjacent to his home town.

His use of a rustic palette of exposed recycled brick walls, brick flooring on sand, sawn timber, galvanized iron roofing, and glass walls fabricated from small steel angles and flats, with triangular “gothic” mullions and coloured glass inserts, all with little or no secondary finishing and with open planning, has been consistent throughout his career.

His mid-period projects, while using similar materials, are less symmetrical and more complex in form and their detailing has an almost Carpenter’s Gothic or hippie style. Klopper’s most recent housing is, once again, more symmetrical and formal, and he has explored and used engineered vaulted brick suspended floors and ceilings with corrugated iron parasol roofs.

In his domestic projects Klopper takes an adventurous and innovative approach to structure, particularly with regard to suspended floors and roof structures. His early houses used exposed timber columns, beams and flooring. These were followed by houses with suspended brick floors supported by upside-down salvaged railway line joists at three-hundred-millimetre centres. His recent vaulted brick floors and ceilings are gravity defying and the lateral thrust on the cavity masonry walls is controlled by steel rod ties or external engaged pier buttressing, or a combination of both. The brick vaults are either reassuringly solid or scarily minimal, depending on your level of structural awareness.

All his work occurs within an urban environment rather than in an open landscape, and is principally in those urban areas that were originally developed in the late-Victorian era for light industrial buildings or workers’ housing. Properties in these areas are now much sought after, of course.

Park Street House shows the “Klopperesque” triangular mullions.

Image: M. Bradley

Klopper attained something approaching cult status in the 1980s, with real estate agents advertising certain properties as “Klopperesque.” His persona closely matches his work, and the words rugged, forthright, outspoken, bush philosopher, bush lawyer, bush businessman and imposing (six and a half feet) come to mind when thinking of him, as well as articulate, intelligent and well-read. His reaction to the predominant professional style of black clothes (dark grey if you are an individual) and architectural jargon such as “paradigm,” “learning vessels,” “infinity plans” etc. is simple – “bullshit.”

The exhibition consisted mostly of a large number of original drawings on tracing paper or clear print paper, the earlier ones hand drawn, the later ones completed using simple CAD programs. They were arranged in chronological order, beginning with Klopper’s first projects undertaken in 1972 with Robert Gare, and ending with projects currently under construction. The drawings reveal a strong continuity in design and the palette of materials. However, the replacement of some of these original drawings with information on the contemporary architectural context, such as selected projects by Wally Greenham, Ralph Drexel and Kim Stirling in Western Australia, as well as the Sydney “nuts and berries” school, may have helped to provide to enhance an understanding of the work.

The Klopper exhibition and accompanying publication celebrated a significant and ongoing architectural career. Klopper’s extensive collection of original drawings has been left to the Duncan Richards Archive at Curtin University, preserved for future scholars.

The exhibitions at UWA do raise the question of how best to achieve exposure, archival storage and easy access. It may well be that in time architects will digitize their own career material and submit it to an open-source archive (such as Wikipedia) for more comprehensive coverage, easier access and easier updating.

Source

People

Published online: 13 Dec 2012

Words:

Marcus Collins

Images:

M. Bradley

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2012