<b>REVIEW</b> Peter Raisbeck

<b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> John Gollings

Connecting Melbourne’s Docklands and the CBD, and design and project management, Grimshaw Jackson’s Southern Cross Station shows the importance of architects to the success of PPP projects.

Aerial view of Southern Cross Station with Melbourne’s CBD beyond and Docklands in the foreground.

The station forms the new corner of Spencer and Collins Streets.

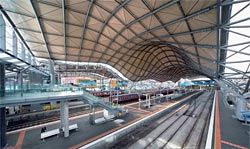

The undulating roof canopy floats above the platforms, with the spines of pillow roof lights providing ample daylighting.

Looking over the pillow roof lights, showing detail of the organic roof form.

The view out towards the city from the Collins Street/Spencer Street entry. The impressive roof structure is exposed internally.

Looking across the train platforms.

Brightly coloured yellow pods contain the station administration.

In global construction markets, Public Private Partnerships (PPP) have become a popular procurement model for the delivery of large-scale infrastructure projects. The transformation of Melbourne’s Spencer Street Station into Southern Cross Station is, to date, one of the largest PPP projects undertaken in Australia and demonstrates the potential for architects to manage risks and create design innovation within this system.

The project cleverly bridges the urban void between Melbourne’s Docklands and the western edge of the CBD grid. Moreover, Southern Cross Station, like the City of Melbourne’s CH2, signals an approach to architecture in which urban design and iconicity is seen as being inseparable from a building’s environmental attributes.

As an urban concept, Southern Cross has been designed without recourse to clichés about Melbourne’s supposedly delightful and labyrinthine laneways. Rather, it was the intention of the architects to reinforce the external and public streets which constitute Melbourne’s grid. Hence, the pedestrian flows to and from the platforms were distributed to the periphery of the building in order to activate the civic life of Collins and Spencer streets. The station appears to be a precursor to Grimshaw’s design for the Fulton Street Transport centre in New York. Like the Fulton Street project, the transparency of the vistas through Southern Cross result in a civic space that locates passengers in relation to the city and results in a new type of urban interior within Melbourne’s grid.

Overlooking the Collins Street and Spencer Street corner space are a series of bars, cafes and retail outlets deftly designed by the architects. This singular space is quite different to the packaged exteriors and shopping-mall-like interiors, decorated with episodic “designer” flourishes, which have become the norm in other large projects within the city’s grid.

The architects have designed a roof over the platforms which is not simply a composition of single arches spanning across each of them. While the initial intention was to create a public space evoking nineteenth-century traditions of transport engineering, the end result is less nostalgic than this might suggest. Instead, the architects have created a customized and public building that is not simply the result of aggregating off-the-shelf standardized elements and component parts. The resultant space under the roof provides various vistas through the station from platform to concourse to street. Indeed, at the scale of the city, the roof reads as a carpet woven from a series of interlinked elements, an urban mat or palimpsest, which rewrites itself over Melbourne’s grid.

From its initial conception, the station’s roof was conceived as an environmentally performative structure. In other words, it was conceived as an element which would function – without the need for mechanical ventilation – as an environmental filter that facilitates the extraction of diesel fumes expelled by the station’s interstate and regional trains. The roof is designed so that diesel vapours rise and are trapped in the upturned wells, and then escape through louvres. These louvres are protected by venturi caps in order to avoid down draughts.

Three-dimensional models of the design show a roof geometry that was initially modelled as a single surface of moguls over each of the station platforms.

The roof geometry was then refined using a computer-generated analysis that modelled the roof’s fluid dynamics at different temperatures.

Considered as a diagram, the roof at Southern Cross evokes various environmental and organic processes and deformations. In modern architecture, ideas drawn from environmental or biological systems have often been linked to the ongoing interest in D’Arcy W. Thompson’s 1917 text On Growth and Form. Indeed, Southern Cross Station seems to echo Thompson’s statement that “any portion of matter, whether it be living or dead, and the changes of form which are apparent in its movements and its growth, may in all cases alike be described as due to the action of force. In short the, form of an object is a ‘diagram of forces’.”1 Likewise, the roof at Southern Cross appears to register the deformations made on its form by the wind and internal air movements. Hence, the roof’s dune-like moguls appear to allude to the techno-organicism of Archigram and the experiments of Buckminster Fuller, David Georges Emmerich and Frei Otto.

In the 1960s, all of these architects sought to apply organic ideas to prefabricated processes and modular systems of construction. In Southern Cross, this techno-organicism has been updated by the use of digital software, and the resultant tectonic plasticity far outstrips Thompson’s musings in On Growth and Form and the experiments of the 1960s. The approach adopted here – the attempt to integrate the tectonic with the climatic via the use of digital software – points to an emerging body of design research in which architecture engages directly with ecological systems.

One constraint imposed on the project was the need to operate the station during construction. This limited the construction methods available and consequently the roof structure had to be designed as a prefabricated entity. During erection, the roof’s individually designed components needed to be structurally self-supporting, and to clear the tracks and associated infrastructure. In order to manage the risks associated with these severe constraints, the architects coordinated and worked closely with the structural engineers and steel detailers. The steel detailing model made for the roof enabled different parts of the roof to be constructed by different steel fabricators around Melbourne. This method of managing the construction, while initially expensive, resulted in minimal RFIs during roof construction.

The PPP approach presents a significant alternative to traditional methods of procurement.

Southern Cross exemplifies the way in which complex products, such as social or economic infrastructure projects, can be designed, constructed and financed using global financial instruments.

This process points to the increasing financialization of architectural design.

In the case of Southern Cross, Civic Nexus, backed by the Australian arm of ABN AMRO bank, won the bid for the station and will be paid an annual fee of A$34 million for 30 years by the Victorian government. In return, Civic Nexus is responsible for operating and maintaining the facility over this time. At the end of the 30-year concession period ownership will revert back to the government.

Under the PPP procurement model architectural design is necessary to reinforce and distinguish the brand attributes of a particular place or facility. This type of branding assists in reducing the volatility of future cash flows emanating from the asset. The construction of Southern Cross, for example, was financed by three bond issues; the third tranche of these bonds was sold to US investors – presumably US pension funds. Equity in the station is now owned by an industry superannuation fund after ABN AMRO, the owners of Civic Nexus, progressively sold equity in the station. Hence, Southern Cross Station Pty Ltd – as it is now known – sits within a superannuation portfolio, as a cash-flow-producing financial asset.

The financial innovation present in PPP projects like Southern Cross should not be conflated with other types of innovation within such projects. In PPPs, the quarantining and allocation of financial risks, often driven by an obsession with “value for money”, is reflected in project outcomes that are constrained by simplistic notions of functional zoning. The strict allocation of financial risks tends to segment a project into simple functional zones, where each zone or segment is an aggregated floor area which produces income. More innovative, integrated and flexible spatial outcomes may result if the architectural design takes place prior to bidding in the PPP life cycle. In comparison to fixed economic infrastructure, such as energy, water and toll road projects, this may be a better option for designing social infrastructure projects under the PPP model. Sadly, the architects’ concept for this station’s roof did not extend to the development of the commercial, retail and spaces to the north of the station, and the distinction is now marked. It is incorrect to naturally assume – as contractors often do – that design innovation created by architects is always costly. The design and innovative methods of construction management and integration in the transport hall could arguably have been extended across the entire site. The roof could have extended a block further north with little extra expense.

A more efficient complex and a subtle mix of retail facilities and public spaces could have been achieved if this was pursued. The irony is that the lessons learnt by the contractor in building the roof were not carried through to the adjacent retail development.

Southern Cross Station raises significant questions about the relationship of finance, design and construction innovation in a PPP context.

The design of the station reinforces the need for the promoters of PPPs to acknowledge the importance of architectural design in branding the station as an urban place, accommodating passenger flows, and foreseeing long-term operational and facilities management issues. The failure of contractors, financiers and policy makers to see architectural design in terms of risk mitigation is the result of perceiving PPP projects as a generic diagram, applied on a whole-of-project basis that quarantines the project’s financial risks from its construction and design risks. This diagrammatic approach risks undervaluing a project’s architectural and urban design attributes.

In the construction of large public buildings and social infrastructure, it is still architects – as this project ably demonstrates – who are capable of bridging the void between design innovation and project management integration across all levels of the project.

DR PETER RAISBECK TEACHES ARCHITECTURAL PRACTICE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE.

FOOTNOTE 1. D’Arcy W. Thompson, On Growth and Form (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1942), 16.

SOUTHERN CROSS STATION, MELBOURNE

Principal architect Grimshaw Jackson JV (Nicholas Grimshaw and Partners in joint venture with Jackson Architecture)—director in charge Keith Brewis; project leader Neil Stonell; Grimshaw project team Ben Beaumont, Taya Brendle, Croz Crosling, Jason Embley, Nick Grimshaw, George King, Barbara Kurdiovsky, Alastair Hudson, Alex Matovic, Mark Middleton, Andrew Milward-Bason, Melissa Lim, Rob Stuart-Smith, Andrew Swaney, Michael Turco, Adrian Watson, Cas Zdanius; Jackson project team Jess Barnes, Julia Beckingsale, Domenic Bono, Liz Doube, Lee Humberstone, Daryl Jackson, Janet Ng, Lisa Ngan, Warren Parker, Brian Richards, Rowan Riley, Peter Stevens, Belinda Strickland, Alex Tucker, Than Tung Lee.

Engineer Winward Structures. Quantity surveyor DCWC and Leighton Contractors.

Builder Leighton Contractors. Services Lincolne Scott Australia.

Environmental Advanced Environmental Design.

Rail infrastructure Maunsell Australia.

Signalling GHD. DDA Blythe Saunderson.

Security Honeywell.

Acoustics Marshall Day.

Roof shop detailing Precision Design.