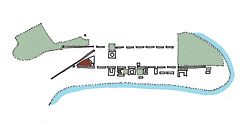

Fig 1 George Street Axis

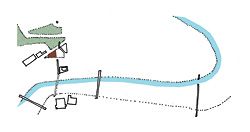

Fig 2 Tank Street Axis

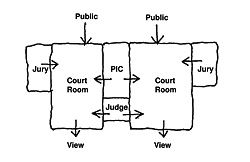

Fig 3 Court circulation schema

Perspective of the proposed foyer.

Perspective of a courtroom interior.

External perspective of the proposed court building, wrapped in a double-skin facade – Renders by Peter Grealy and Simon Perry

Though the location of the new Brisbane Supreme and District Court was decided only recently, it is as though the site had been earmarked for this purpose since the city was first surveyed. At the western end of George Street, Brisbane’s colonial civic axis, the new site is a bookend to the House of Parliament at the eastern termination of the axis, with the Executive Offices of Government in the centre.

Distributed within this symmetrical arrangement of the “separated powers”, a number of other important civic buildings of considerable architectural merit, including the original Government House, the new council headquarters and the famous Treasury Building, give strength to the axis. Each of these civic buildings is accompanied by a significant square, and it is the presence of these squares as much as the buildings themselves that gives the street its civic quality. Fortunately, a last-hour decision by the government to allocate a much larger parcel of land than was originally canvassed has allowed the new court building to be accompanied by a substantial open space (Fig 1).

When Brisbane’s new Gallery of Modern Art was designed by Architectus on the South Bank site across the river from the CBD, it identified a significant cross axis to George Street. This Tank Street axis runs across the river from the gallery, along Tank Street and up to the Old Mill on Wickham Terrace. GoMA and its central public hall were aligned on this axis, which, coincidentally, bisects the site for the courts building. When the gallery was designed, the Tank Street axis was purely visual and this alignment, placing the gallery some degrees off the surrounding South Brisbane grid, was a strategy to metaphorically connect it with the city grid and the CBD.

Since then, a new pedestrian and cycle bridge linking South Bank with the CBD has been designed and is currently under construction. The visual axis is therefore in the process of becoming a physical one and a very significant one for the inner city. Sectional issues dictate that the bridge will actually touch the ground on the CBD side of the river halfway along Tank Street and quite close to our carefully located square. In positioning the square and maintaining the clear visual axis up to Wickham Terrace, our intention is that the square should become, in effect, the entry point to the western end of the CBD from South Bank, and a significant urban space in its own right. This urban significance has led us to give a deliberate non-ceremonial use to the square, and its large grass areas and shaded arbours encourage its use as a normal inner-city square (Fig 2).

We knew from our own research and from the expressed desire of judges that courtrooms with an external aspect and with natural light give better trial outcomes. People are more relaxed and are able to concentrate for longer periods of time in healthy, day-lit spaces with a direct relationship to the outside world. Having seen a number of European courthouses, including Henri Ciriani’s wonderful Pontoise Court of Law, full of calm and light and civic presence, we felt this approach would be appropriate in the subtropical Queensland context.

Australian courts operate under more demanding security and functional regimes than their European counterparts. Further, an Australian court, of similar jurisdiction to a European court, requires about seven times the number of courtrooms. Where European courts are usually single-storey, with the capacity to let in light from overhead as well as from the side, an Australian court of similar scale will always be multi-storey and will require at least four separate and secure circulation routes to each courtroom – one for the judiciary, one for persons in custody, one for the jury and one for the public. Australian court design requires that each circulation path for each of these users is kept visually, aurally and physically separate throughout the building.

In simple terms, if judges access all the courts on a single floor from a common lift, then there is likely to be a corridor between the courtroom and the outside, with little opportunity for significant visual connection between inside and out. Our first step then was to provide a separate judicial lift for each pair of courts, immediately freeing up the external facade to the view (Fig 3).

Before we could create a full glazed external wall (and high-level glazing to the remaining walls), the initial concept design was developed to respond to a number of stringent design parameters related to the courtrooms. It is simply not acceptable to have a courtroom where direct sunlight enters the court, where people outside can see into the court, or where external sound can enter the court. The inside–outside relationship is really a one-way relationship. However, we did want to promote the idea that the judicial institution is transparent and not cut off from the public it serves. To the greatest possible extent we wanted to reveal what we could of the inside workings of the building to the people on the street and in the square without compromising the strict performance parameters.

The archetypal subtropical space is an open space, under a large roof, with a layered set of screens that modify the external environment to render the interior space habitable. We have taken a similar approach. Each floor sits beneath a broad, flat, concrete soffit. No internal solid walls reach the soffit but are glazed on their upper sections so that space and light flow continuously across the full ceiling plate of each floor. This interior is punctuated only by the vertical cores between the courts, which orient people within the space.

The building has then been wrapped in a double glass wall, the two layers separated by a 1200-mm cavity, which houses solar blinds on an automatic control system tuned to the solar path. The cavity assists external acoustic isolation and thermal insulation. Strategically patterned fritting distributed across the two layers of glass provides visual privacy where required, and it is scaled so that external views are maintained while views into the building are fragmented.

From a green building perspective, the project has developed a building-specific rating tool, as none exists for court buildings. Though the building has been designed and tested using this tool, we have also included a number of energy-saving initiatives which do not necessarily contribute to the five-star-equivalent rating.

The design provides two large underground water storage tanks. A 1.2-million-litre thermal energy storage tank reduces the peak airconditioning load, and a 600,000-litre stormwater recycling tank provides all the irrigation for the building and the square. Rooftop photovoltaics provide for full night lighting of the building, and solar panels provide for hot water requirements.

The mechanical ventilation is a low-energy displacement system, with 100 percent fresh air intake when external conditions are appropriate. The displacement system has been used for its energy efficiency and its suitability for court buildings, where rooms are irregularly occupied but need cooling at short notice. The building is mainly used during daylight hours and is extensively day-lit and oriented with public galleries to the north. The sophisticated double-glazed facade provides full solar protection and good insulation and promotes a healthy internal working environment.

All car parking is provided with power outlets for future battery recharging, all timbers throughout the project are plantation-sourced and all materials are low-VOC.

The expected completion date is December 2011.

Credits

- Project

- Brisbane Supreme and District Court

- Architect

- Architectus

Australia

- Project Team

- John Hockings, Lindsay Clare, Patrick Clifford, Mark Wilde, Ralph Bailey, Phil Jackson, John Grealy, Henry Hancock, Ashley Beckett, Juan Benavides, Kelly Burke, Mark Burrowes, Stephen Chandler, David Toussaint, Craig Earley, Katia Gard, Adrian Hanby, Mark Hogan, Queila Kleemann, Klara Kormendy, Stephen Long, Anthony McKibben, Fedor Medek, Anya Meng, Bill McIlwraith, Melinda Morrison, Jessica O'Shea, Robert Ousey, Rohan Patil, Kurt Piccardi, Ray Smith, Kirk Smith, Erik Sziraki, Keith Ward, Erin Wheatley, Stacey Carroll, Nadia Casati, Kalene Cassie, Sam Charles-Gin, Kirstie Galloway, Juliana Hannah, Glen Hartman, Matthew Herzig, Brett Linze, Andrew Jones, Georgia Kirkwood, Min Kyu Lim, Ashneel Maharaj, Cherissa McCaughey, Simon Moisey, Angus Munro, Michael Ray, Richard Stone, Janina Thieme, Anna van Hess, Nich Josephsen, Angela Morton, Christina Renger, Joel Sim

- Landscape consultant

- Guymer Bailey Landscape

Toowong, Brisbane, Qld, Australia

- Consultants

-

Acoustic and facade consultant

Aurecon Brisbane

Audiovisual consultant Aurecon Brisbane

Building certifier Philip Chun & Associates

Construction manager Lendlease

Construction surveyor Lyons Engineering Surveyors

Digital illustrations Pogo Digital

Disability consultant Access All Ways

Documentation Ranbury Management Group

ESD Steensen Varming

Electrical and mechanical consultant Aurecon Brisbane

Electronic services Aurecon Brisbane

Engineer Aurecon Brisbane

Fire services Aurecon Brisbane

Furniture, fixtures and equipment RGC Consulting

Hydraulics Thomson Kane Hydraulic

Landscape consultant Edaw

Lighting Steensen Varming

Model maker Model Consultants International

Quantity surveyor Wilde and Woollard

Security consultant Aurecon Brisbane

Signage and wayfinding Dot Dash

Structural and civil consultant Aurecon Brisbane

Surveyor Bennett and Francis

Town planning Buckley Vann

Vertical transportation Aurecon Brisbane

- Site Details

-

Location

415 George Street,

Brisbane,

Qld,

Australia

Site type Urban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Public / cultural

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Sep 2009

Words:

John Hockings

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2009