Denton Corker Marshall has a long tradition of entering (and winning) competitions. So in 2002, when the competition for the new Manchester Civil Justice Centre came up, we submitted our Expression of Interest.

Manchester Civil Justice Centre

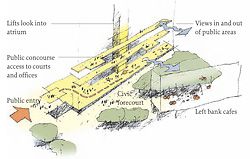

Exploded axonometric of the Manchester Civil Justice Centre.

The Manchester Civil Justice Centre reads as a signal and civic marker to the approach to the city centre.

Interior of a courtroom at Manchester.

Gross internal floor area: 34,000 m². Total cost: £112 million.

Major government projects in the European Union are required to be advertised in the Official Journal of the European Community, which allows any company within the EU to register interest. The Lord Chancellor’s Department of the United Kingdom (now the Ministry of Justice) advertised for Expressions of Interest in participating in a competition to design the new Civil Justice Centre in Manchester – a substantial project, with forty-seven courts and the headquarters of Her Majesty’s Courts Service (HMCS) for the north of England. It is the largest courts complex to be built in the UK since the Royal Courts of Justice in London in the nineteenth century.

We felt like the proverbial wild card entry when we found we were in the final three but up against, on one hand, Richard Rogers Partnership – Lord Rogers having built the European Court of Civil Rights in Strasbourg and sitting in the House of Lords with the Lord Chancellor – and, on the other, a well-known Manchester-based firm. However, we gave it our best and we won.

The underlying conservatism and hierarchical character of the judicial system in the UK quickly became evident. For example, the brief called for one basement car space for each judge but the four High Court judges’ spaces had to be oversized to allow for Rolls Royces! The disposition of courts meant that the more senior the court, the higher up the building it should be. In our design, however, we had moved all the justices’ retiring suites to the top of the building along with their library, lounge and dining areas. We won the competition with this arrangement, but when presented it became evident that this was unacceptable to the senior justices and the retiring suites were redesigned to be spread throughout the building and related to the different court floors.

The new courts are situated in the centre of Manchester, adjacent to the crown courts and magistrates’ courts in the Spinningfields redevelopment zone. The site was the preferred one, but the government chose it and the developer via a form of privately financed initiative, unrelated to the design of the building. The brief to potential developers was for a site and a rental per square metre for A Grade commercial offices on a twenty-five-year lease. The government then paid directly for the enhancements required to create courts. This has meant that the government and the developer each contributed around half the cost of the building.

Once the site was chosen, the competition for the design took place and the architects and their winning design were handed to the developer. The developer asked us to go to detailed design, negotiated a guaranteed maximum price (GMP) from a building contractor and then simultaneously novated us to the contractor, signed up the contractor based on the GMP and signed an agreement with the government to meet their landlord’s requirement document (effectively our detailed design). The government in turn agreed to lease the building for twenty-five years at the base building rental and pay for the enhancements.

To our amazement that actually happened.

The Civil Justice Centre’s height allows it to read at city scale in distant views. It also reads as signal and civic marker to the north-western approach to the city centre. The working courts and offices establish the substantive form of the building. They are expressed as long rectilinear forms, articulated at each floor level and projecting at each end of the building as a varied composition of solid and void. They are held between the solid plate of the structure and services spine and the perforated plane of the judicial layer. In side elevation, these elements collectively establish a distinctive building profile; in end elevation, they form a sculptural interplay of light and shade, depth and complexity.

These elements allow a reading or sense of individual courts, without explicitly defining them. They are double-skinned. The outer layer of clear glass defines a singular, simple volume. The inner layer defines the interior volume, softened by the overlay of glass but allowing a more complex and detailed reading of material, colour, pattern, glazing and surface, while retaining an overall clarity of form. The architectural implication is that the courts are not forbidding and concealed, but open and accessible.

Daylight, natural ventilation, solar shading and groundwater cooling have been used to reduce the building’s carbon footprint, saving energy costs and, most importantly, meeting HMCS’s brief for “a sustainable building of civic generosity and European significance with minimal impact on the environment”. The high aspirations for the project were set at the earliest stage by the Lord Chancellor, who demanded that it demonstrate the government’s commitment to the Better Public Building initiative established by CABE.

The tall, narrow form of the building encourages natural ventilation. This was the fundamental difference between ours and the other two competitors’ schemes – they opted for lower buildings covering the whole site. Once a building gets more than fifteen to eighteen metres deep, it’s hard, even utilizing prevailing winds, to get the air to move through the building. Our scheme was the most complex to achieve, but successfully incorporating natural ventilation to each of the courtrooms elevated the building’s environmental credentials.

Maximizing the use of daylight, natural ventilation, solar shading and groundwater cooling reduces the MCJC’s carbon dioxide emissions by around 505 tonnes per annum, with emissions/m2 treated area at a level of 53.6kgCO2/m2. Overall energy consumption is reduced by around 20 percent. These measures have helped the MCJC to receive a BREEAM Excellent rating.

So while the ESD is effectively invisible, the building is a major exemplar for government buildings in the UK, not only for its ESD but for the importance the government placed on design quality under the Better Public Building initiative of CABE.

As a result of working with HMCS, we subsequently submitted credentials and were accepted as members of a framework panel of five architects to carry out work for them, both in building design and in advice at the business case stage for potential projects. Panel work has included advising on commercial courts elsewhere in the UK. It also included a direct appointment to design the new Birmingham Magistrates’ Court in 2007.

Birmingham Magistrates’ Court

External perspective view of Birmingham Magistrates’ Court showing the curvilinear silver metal “gown” from ground to roof level.

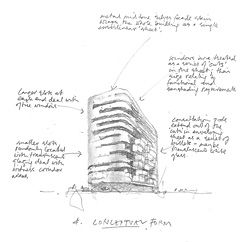

Concept sketch for Birmingham Magistrates’ Court describing the series of irregular horizontal cut-outs in the facade.

Interior view of the proposed courtroom at Birmingham.

Gross internal floor area: 20,600 m². Total cost: £81 million.

The Birmingham Magistrates’ Court building will comprise twenty-four courtrooms plus ancillary accommodation for staff, judiciary, witnesses, defendants, legal professionals and members of the public, approximately 20,600 square metres over thirteen levels. The courtrooms will be located on levels one to six, with four courtrooms per floor. General administration and judicial accommodation will be located on the upper four floors of the building. These will wrap around a central internal atrium to create a dynamic and interactive working environment.

The building will be clothed in a single curvilinear silver metal “gown” from ground to roof level. Into this surface, a series of irregular horizontal slotted and stepped cut-outs will provide daylight to courtrooms and public consultation areas. At court level, translucent white glass-clad boxes containing consultation and magistrates’ retiring rooms will cantilever beyond the curvilinear surface, reflecting the rectilinear nature of the internal planning and offering a more complex external reading of the building form.

We wanted to give it an expressive and special character. A singular sculptural curved form, perforated and punctuated, makes a civic gesture in the company of the commercial and residential buildings that surround it. The new building will be located close to the city centre and will provide a landmark within the Masshouse Masterplan. The project has achieved full planning approval and construction is due to commence on site in March 2010.

Parallel to this, HMCS alerted us to private finance delivery opportunities (in effect Public–Private Partnerships) and we are currently on shortlists for new courts in the Greater Manchester Area and the new Liverpool Magistrates’ Court.

Liverpool Magistrates’ Court

Gross internal floor area: approx 11,300 m².

Total cost estimated at £40 million.

Her Majesty’s Courts Service identified an urgent requirement to replace the existing accommodation for magistrates’ courts in Liverpool. The existing magistrates’ court buildings are currently spread over four buildings, which have become inefficient and provide inadequate facilities for the operational needs of HMCS. The intention is to consolidate the operation into a single bespoke building by the final quarter of 2011.

The site is within a challenging and impressive location overlooking the River Mersey. Liverpool played a leading role in the development of dock construction, port management and international trade in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Buildings and port structures provide an historical context and testify to the mercantile culture of the area, which has achieved World Heritage Site status. The site borders this area and lies within the buffer zone to the World Heritage Site.

The site is also conveniently positioned next to the existing Queen Elizabeth II Law Courts and provides the potential for a new legal hub in the city centre. Some of the city’s major barristers’ chambers are located close by, to the north of the site, which intensifies the sense of an identifiable “legal quarter”, and the area is served by a network of public transport hubs and pedestrian routes.

The new Magistrates’ Court will house fourteen courtrooms and office and ancillary accommodation to serve its purpose, with dedicated prosecution witness accommodation to reflect the ever increasing requirements for witness protection. This adds a level of complexity to the circulation routes within the building and creates an architectural challenge to provide operational services in an effective and efficient way. Proposals are designed to be compliant with all HMCS design guide requirements, be fully accessible to all parts of society, meet the requirements regarding sustainable development and provide a BREEAM Excellent rating.

Greater Manchester Court Project

Bolton Magistrates’ Courts

Gross internal floor area: approx 7,750 m².

Total cost estimated at £30 million.

Salford Magistrates’ Court plus car park

Gross internal floor area: approx 8,950 m².

Total cost estimated at £30 million.

As part of the ongoing court modernizing program, Her Majesty’s Courts Service identified an urgent requirement to replace the existing accommodation for magistrates’ courts in Greater Manchester in the regional areas of Bolton and Salford.

Both buildings lie on sites in close proximity to the town centre but in unimposing contexts, so the architectural statement is limited to a regional aspiration by the client rather than a more substantive statement as experienced on other city centre sites.

The new Magistrates’ Courts offer ten courtrooms and office and ancillary accommodation, with dedicated jury accommodation. Both proposals are again designed to be compliant with all HMCS design guide requirements, be fully accessible to all parts of society, meet the requirements regarding sustainable development and provide a BREEAM Excellent rating.

Apart from the resolution of the complex circulation problems of courts in a contemporary way the most significant changes to courtroom design has been to make them more open and friendly and accessible and, of course, sustainable.

To quote the Lord Chief Justice on the Manchester Civil Justice Centre: “… modernity has not compromised the atmosphere of order and authority, so essential to a place dedicated to the rule of law. The fact that this building is an award winning piece of modern architecture, and a talking point literally across the world in terms of its bold execution of a unique vision, in no way detracts from its fundamental purpose: to provide a welcoming, yet businesslike environment in which people may exercise their legal rights … this Civil Justice Centre has quite literally transformed the landscape for civil and family justice in Manchester.”

John Denton is a director of Denton Corker Marshall.