Venice is spectacular. The thrill of arriving by train, spilling out onto the canal-front plaza and being swept into the channel by vaporetto is only enhanced by the pageant of gondola-rocked tourists. The city is a theme park of palaces, odd transportation, photo opportunities and souvenir sellers. And, as if its setting wasn’t enough, Venice is the host of annual blockbusters from the film festival and Carnevale to the alternating art and architecture biennales – spectacles within the spectacular.

The main events of the architecture biennale are housed in the Central Pavilion of the Giardini and the nearby Arsenale, at the eastern end of the island. Fringe exhibitions are scattered throughout the archipelago. In the year preceding each biennale, a creative director is appointed and a theme chosen to guide invited participants. The national pavilions, distributed expo-like through the Giardini, may, depending on their lead times, have displays explicitly addressing this theme. The biennale now extends for six months, which, when taking into account time for bumping in and out, means the public gardens are effectively privatized for most of the year.

The creative directors for Australia’s 2016 effort, Aileen Sage Architects (Isabelle Toland and Amelia Holliday) with Michelle Tabet, were appointed in April 2015, six months in advance of festival creative director Alejandro Aravena and the announcement of the theme Reporting From the Front. Adaptability to any overarching subject was a criterion for selection of the Australian proposal and The Pool could go with the flow. As communicated in the original submission, the concept for The Pool was perhaps more architectural – a physical intervention in the space supporting a survey of exemplars. But in reaction to the humanitarian-focused biennale theme, it seems the drama of architect-designed projects has been deserted in favour of the broad appeal of “storytelling.”

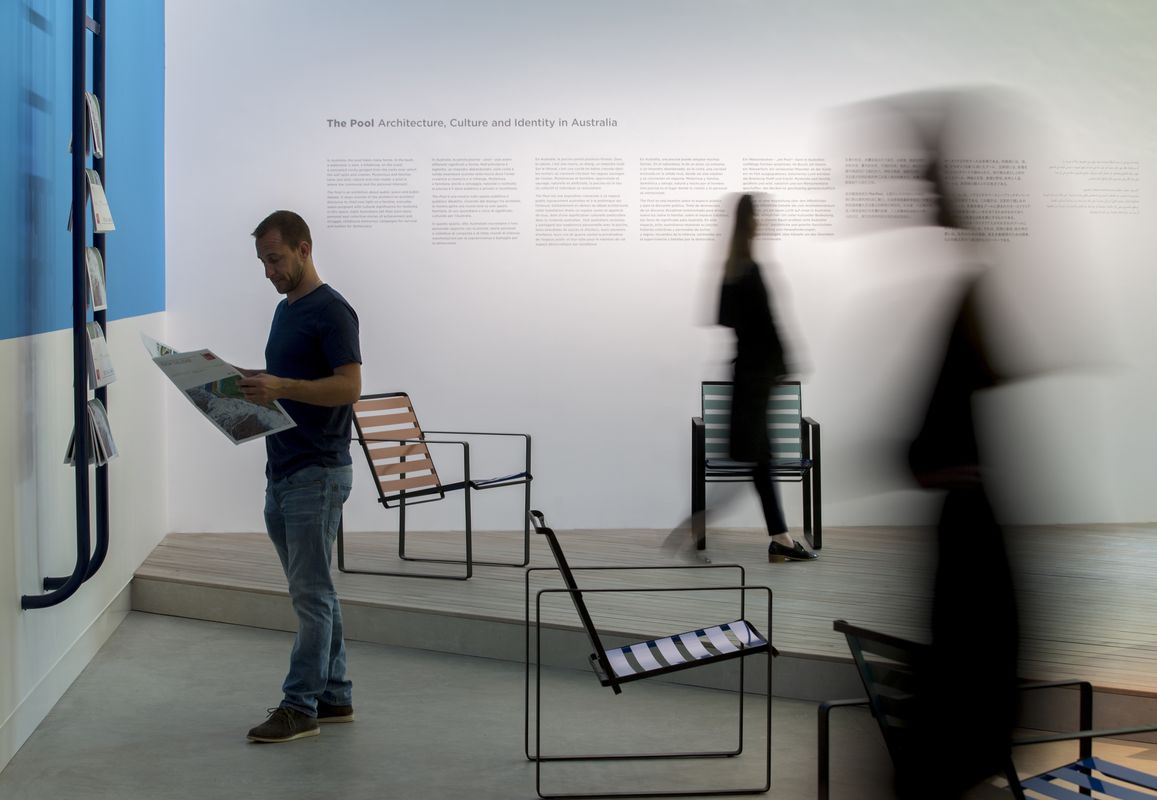

The Pool, Australia’s exhibition at the 2016 Venice Architecture Biennale, curated by Aileen Sage Architects (Isabelle Toland and Amelia Holliday) and Michelle Tabet.

Image: Alexander Mayes

The Pool is the first architecture show in Denton Corker Marshall’s new, permanent pavilion – a black-granite-clad cube with tabs that fold open over a square door and windows to reveal a white-box interior. Arrival is via a hot-concrete balcony girt by frameless glass balustrades, a hint of the Aussie pool experience within. Padding past the lobby booksellers and around a dust-red wall, one enters the pool hall: a sparkling, echoing volume with the footprint of a backyard but the acoustics of a swim centre.

A distorted pentagon contains the water. Knee deep, steel shelled and sheathed with grey vinyl, the pool has the evocative effect of a Clark Sunsoka but, in truth, represents the peak of Italian manufacturing technology. The leading edge of the tank slices diagonally across the space, a triangle cleaved from its left side to give access to the canal-overlooking window. A rise of decked steps at its western end leads to faded silvertop ash bleachers.

A simple tubular handrail guides visitors across a plastic gridded platform into the basin, as if from the showers to the pool. The mesh is repeated just above the waterline at the other end, perhaps a nod to the similarly angular Villa Marittima by Robin Williams Architect, one of the few explicitly architectural projects mentioned in the accompanying book.

A reflective wall panel is positioned at the eastern end to expand the apparent length of the stands to the scale of a public pool, as seen from the front. From the perspective of the deck, the pool surface is doubled into the shape of an angular kidney. When viewing the entrance from the bleachers, the references to Hockney are clear, with an intense blue wall/sky and paler turquoise water mirroring his A Bigger Splash across the golden wedge of pool edge and terracotta-blocked entry portal.

Visitors during the vernissage made full use of the installation.

Image: Brett Boardman

Along the north-west corner, white changeroom benches support the wireless-style speakers broadcasting reminiscences of Australian cultural identities and underline the migrated warning of Fitzroy Pool: “DANGER DEEP WATER AQUA PROFONDA,” the only message (mis)translated in the space or the documentation. No signs forbid a quick dip and kids at the vernissage waded right in. One adult exercising his right to joyous engagement and a few quick laps was allegedly whistled out by La Polizia.

Custom-designed steel deck chairs furnish the cement margin, marrying the square geometry of the pavilion with the angles and colours of the pool. Resting here one can read the broadsheet: a tabloid-sized takeaway offering a taste of the larger book for sale. Escaping papers are tidied away on an elongated blue pool ladder … or perhaps it’s a heated towel rail for the comfort of autumn nippers (the exhibition closes in November).

The installation responds to the architecture of the pavilion, with reflections from the canal integrated with those from the pool.

Image: Brett Boardman

In a city of spectacle, The Pool installation is, rather, sensational. Great care has been taken to integrate reflections from the water of the canal with those from the pool, engaging the architecture of the pavilion in the atmosphere of the exhibition. Full-scale mock-ups were built in a studio in Sydney to test the lighting effects, and scenes were developed that alter during the passage of the day, amplifying the effect of sunshine and sunset through the building’s aperture.

A soundscape of xylophonic gurgles and plinks fills the air between the storytelling, and the room is perfumed with “burnt bush” and wet leaves (not chlorine – the water is bromine-filtered). The content is more easily apprehended when the pavilion is empty, the stillness encouraging contemplation, but with the surge of a vernissage crowd the energy better invokes the experience of public pools, appealing to the biennale theme.

The installation is taut with the effort of making the taxing seem fluent. It is a masterwork of facilitation, managing multiple contributors, juggling manufacturers in diverse geographies and satisfying sponsors, commissioners and government-granters. Soundscapers, scent makers and scarf printers are all showcased. The only creatives under-represented are architects.

Aravena’s theme is not only about architecture as an agent of change; it is also about the right of all to deep quality in the built environment. The pool can, through the efforts of architects, transcend infrastructure, rising above utility and salubriousness. But, perhaps out of fear of “archi-speak,” the directors have avoided asking professionals to address spatial, conceptual or aesthetic experiences. Fearing distraction from a phenomenal appreciation of this impressive installation, the mooted “exploration of notions, concepts and places” by analysis of projects has been abandoned. Profundity has been evaded.

Many mocked the ambassador for his trade-linked launch, but the biennale is, after all, an exposition, an exertion of soft power. And yet, despite the fact that the concept has been dampened in order to engage a wide audience, and in spite of an effusion of supporting media and events (podcasts, pamphlets and parties), The Pool remains ultimately exclusive in that it can only be experienced fully in Venice. It’s a stage without a show.