On 10 September 2014, Urban Taskforce Australia, a developer lobby group based in Sydney, launched the “Towers and Transport” edition of Urban Ideas, a self-described public interest magazine. In his introduction to the edition, Chris Johnson, Urban Taskforce’s CEO, points to a projected increase in Sydney’s population of 1.6 million over the next 20 years. Carried across fifty years, these figures, Johnson suggests, will necessitate the construction of 33,200 new homes each year, totalling 1.66 million over this period. Essentially, a doubling of the number of Sydney houses, all seen within the lifetime of your average Gen Y Sydneysider.

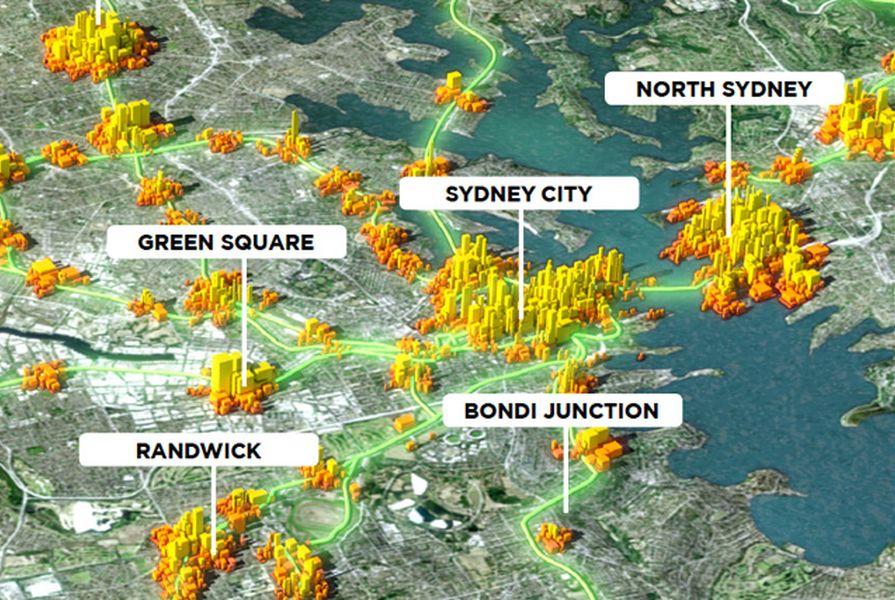

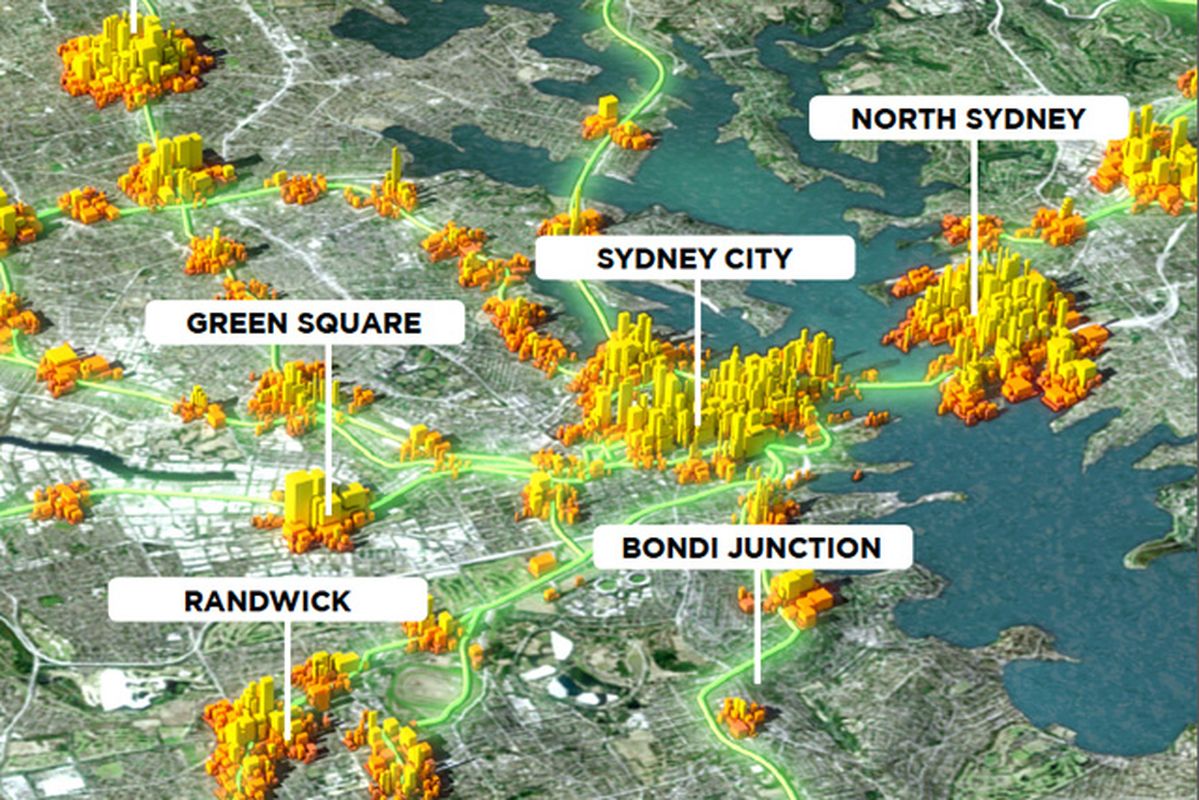

In response, the Towers and Transport edition of Urban Ideas calls for mammoth densification: the construction of 5000 towers at major rail transit nodes. This, the Taskforce claims, could accommodate a third of the projected population increase. It is a proposal for a density network, “a city of cities” growing from our rail lines that theoretically harks back to John Bradfield’s original railway scheme for Sydney.

To offer further reasoning behind the drive for more towers and transport, the Taskforce invited Vishaan Chakrabarti of SHoP Architects to give a presentation at the launch of the magazine. Chakrabarti is the most recent principal for the SHoP team, a director of Columbia University’s Centre for Urban Real Estate (CURE) and a former director of the Manhattan Office for the New York Department of City Planning. His talk approached density from a global sustainability perspective.

Public open areas of SHoP Architects’ Domino Sugar Refinery apartment complex in Brooklyn, New York.

Image: SHoP Architects

As Chakrabarti pointed out, while many studies point to the fact that the world is urbanising, they rarely differentiate between “urbanising” and “suburbanising”. Sydney’s suburban structure stems from what Chakrabarti described as “houses, hedges and highways”. Like many American cities, Sydney’s suburban growth accelerated during the long boom period after WWII – a time that saw the two- car household dream accelerate thanks to stronger government investment in roads than in public transport (a trend still continued in our federal budgets today).

Cities were once associated with poor health and not considered desirable places to live; today, we are witnessing an inversion of these perspectives. Those living in our outer suburbs are likely to be unhealthier and less socially mobile than their inner-urban counterparts, while long commuting times correlate to higher than average rates of divorce. In Sydney, though, affordable housing is being pushed further and further away from the city’s knowledge centres. So, while from a sustainability perspective “the earth simply does not have the resources to support billions and billions of people living that way”, to use Chakrabarti’s words, from a socio-economic perspective it’s not crash hot either.

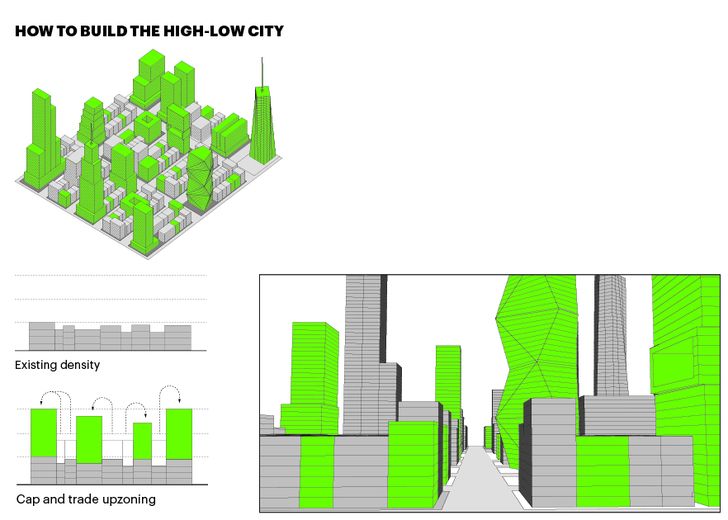

A “transit oriented development” future for Sydney isn’t a projection, but an emerging reality. As Chakrabarti put it, though, “you don’t just promote density above transit – that is a necessary condition, it’s not in my mind a sufficient condition. The sufficient condition is to prove to people that you are going to create a great experience for them in their lives… [and] we need to be more realistic about how we are going to get there.” By this, he refers to what he labels the “High-Low City” – a fusion of building heights and types, in contrast to the Taskforce’s proposal for spiky clusters of high-density towers, not “tall buildings with tall buildings, short buildings with short buildings”.

“Unfortunately, this kind of attitude is built up in our planning discipline and it is driven by this idea of predictability… That you are going to know how tall the building next to you is going to be,” Chakrabarti said. “But the problem, of course, is the most beautiful cities in the world, like the most beautiful things in life, are unpredictable.”

Image: SHoP Architects

To embrace said unpredictability, SHoP’s approach favours a public-private trade-off, where regulations become a flexible basis for negotiation. This is a common theme within its work, a prime example being the Domino Sugar Refinery site in Brooklyn, New York. A complex of 2200 apartments currently under construction, the plan here gained community support for increased building height by freeing up open foreshore space for the public. In addition to incorporating a school and community centre, the developer agreed that shops within the mixed-use development would not include chains or big box retail.

As Chakrabarti reflected, “The problem is that regulations are set up to prevent the worst thing from happening, they’re not set up to incentivise the best thing.” Considering the day’s theme of towers and transport, Chakrabarti continued, “We need to talk about infrastructure in a broader way, what I like to call an ‘infrastructure of opportunity’… if we are going to talk about density, then we also need to talk not just about the hard infrastructure we need, like transit, but the soft infrastructure we need, like culture, education, affordable housing, the things that people are going to want as part of a densified city.”

In full, simply allowing for ground floor retail and public space isn’t enough: solutions lie in means which reach beyond the base-line provision of ground floor activation and mixed use building types. A flick though the pages of the new Urban Ideas magazine reveals a discussion of “varied urban morphology with civic benefits,” “quality communities”, “integrated public infrastructure” and “sustainable public realm focused on rail corridors.” Yet these words are followed by pages of residential towers, predictable development types that arguably barely scrape the bottom of these high-minded notions, pointing to the void that exists between what is being developed and what is being discussed. In its top-down focus on big towers and big infrastructure, the Urban Taskforce seems to have forgotten about the fine-grain, bottom-up, human scale that informs the success of any healthy city.