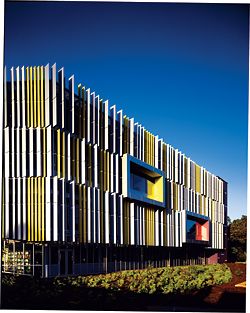

South elevation facing the entry forecourt. The close vertical cladding gives a monumental, formal quality.

The library forecourt at night, when lighting renders the public facade more transparent.

Detail of the horizontal coloured louvres on the building’s less formal northern facade.

Entry to the cafe, which stretches out on the northern side of the library and protrudes into the entrance foyer.

The northern facade, overlooking a Japanese-inspired timber courtyard, forms the internal campus elevation.

Looking down into the foyer, with the entrance on the right and the e-lab straight ahead.

A group study area. Couches built into the window boxes often feature reclining students.

The serials and reference stacks on level 1, below the main entry, with courtyard beyond.

Traditional carrels support contemporary technology in the e-lab.

Access to comprehensive and quality library resources is fundamental to education and lifelong learning. The principle of access is a useful way to understand the design and use of the new Library and Resources Building at the Edith Cowan University (ECU) Joondalup campus. This building by Jones Coulter Young (JCY) revolves around the issue of access in its many dimensions, which can be described in terms of “way in”, “right of entry” and “getting into” (which is also to say “logging on”).

Firstly, the way in. Physical access to the building relates to its location and siting and operates at the regional and campus level. The library was designed in accordance with the university masterplan, which proposes a westward shift in the centre of gravity and density of the campus, away from the park-like setting of the internal lake (near which JCY’s earlier Science and Health Building is located) towards the commercial edge of Joondalup Drive and Grand Boulevard, bordering Joondalup’s city centre. The library is the most prominent building in this corner of the grounds and, as such, anchors and anticipates many significant masterplanning gestures that will fortify this as the new student heart of the campus.

The notion of “the way in” is also intricately connected to the library’s organization and circulation – in particular, the means by which users and visitors navigate around and through the premises. In plan the building is a kinked rectangle, segmented into three roughly equivalent parts. The achievements of this bending are numerous, starting with reconciliation of the network of extant and future axes that effectively organize the physical form of the campus and movement through it. In addition to proposed new pathways bringing pedestrian traffic to the building, an existing main vehicular entrance off Joondalup Drive delivers visitors to the library forecourt. This is properly the building’s more public face, expressed through the close vertical application of coloured louvres, which from various vantage points appear to solidly sheath the otherwise glazed wall. Entry to the building is from both sides in the central segment of the middle of three floors that house the library functions (a fourth supports other university accommodation). Inside, a cranked stair climbs one level to the main collection or descends to the serials and reference stacks. Internal circulation is coherent, following the logic of the kink and reiterating the pinwheeling effect generated by the building’s alignment with multiple axes.

The bending also effectively defines the library’s two main outdoor spaces. The western end closes toward the entry to create the public forecourt; the eastern elbow captures a more private, Japanese-inspired timber courtyard on the northern side. The courtyard is effectively the internal campus elevation. It is thinly screened by horizontal louvres, which provide necessary shading as well as contrasting with the densely shuttered and more monumental public side. From both sides, the library is a major gateway to the campus, and in university publications it is used to symbolize the mission, values and goals of the institution. It is an aperture or portal both real and virtual, as represented by the oversized window-box motif.

Given this function of gateway or aperture, the configuring of the main entry level is of special interest. Flanking the entrance axis and in close proximity to the enquiries counter, the architects have assembled a cafe, bookshop and e-lab. While cafes and bookshops are not new in library buildings, here the protrusion of the cafe space, furniture, noise and music into the library foyer is unexpected and yet strangely familiar. Although it’s perhaps an unlikely comparison, this building’s public space is strongly reminiscent of an airport transit lounge. Such is the atmosphere of this transitional zone of the library, activated and punctuated by a great deal of coming and going, passing through, coffee-grabbing and, to use deliberately multivalent terms, networking and browsing. This is the hub: not only of the library, but also, given this building’s prominent role as gateway to the campus, of the university in a physical and perhaps more especially metaphysical sense. And it is here that the issue of access touches on the right of entry.

By this I mean the sense that a user has of their right to enter, their right to use the space and its facilities. The architects have attempted to design what American urban sociologist Ray Oldenburg calls a “third place”, a meeting place that is outside of the “first place” of the home and the “second place” of work. Third places are defined by their high level of accessibility. Among other things, they are affordable, are within walking distance of many users and support regular gatherings of various communities. In addition, they perform a levelling function by promoting social equality. Oldenburg says that cafes, pubs and main streets are third places – perhaps transit lounges and libraries are too. The relevance of this idea to the ECU Library is shown in its incorporation of home comforts and familiar experiences within a realm that was previously associated with silence and reserve. In JCY’s building, students sprawl in beanbags with laptops; they recline on couches built into the projecting window boxes. There is even debate within the institution about whether to eradicate the ban on eating in the library.

As a third place and as a kind of transit lounge, the ECU Library is both destination and portal. It is a physical, digital and bibliographic gateway to other places. And if access is operating at the level of way-finding and admission, it is also about getting into (and logging on to) the library’s many and varied resources. It is, in other words, about reading. At one level it seems that the state-of-the-art facilities and diversity of spaces accommodated in the library of today (this one included) make it a place far removed from those of the past. However, without overlooking what is clearly a dynamic learning experience in the ECU building, it is clear that here and in other recent examples (such as Edmond and Corrigan’s Academic Centre for Newman College and St Mary’s College at the University of Melbourne), the core purpose of the library has not been replaced, but amplified. The provision of flexible access to learning materials and the diversity of the collections have always been central to creating a stimulating environment that promotes critical thinking and lifelong learning. Reading of all kinds – books, journals and serials, maps, images, archives, digital information – is the library’s core business. Not for nothing did Ashton Raggatt McDougall (pre)face the St Kilda library (1992) with a weighty bluestone tome laid open. The library still revolves around the access achieved through reading, but today numerous activities, facilities and spaces supplement and enhance the reading process. In JCY’s library, reading happens in the traditional settings: in the books stacks, the carrels, the browsing areas. It also happens in the quiet study areas and the group study rooms, in the northern courtyard, the bookshop and the cafe. In the contemporary space of the e-lab it is on-screen and online; in break-out and other new spaces that blur traditional pedagogical distinctions, reading informs conversation. Reading here is still an individual pursuit and often a silent one. But it is also an activity shared, silently or aloud.

It is possible to see this primary function writ large in the building – window box as portal, vertical louvres like books stacked on a shelf or like pages of an open book, massive internal signage painted in signature JCY colours inspired by local flora. Recipient of the 2007 RAIA (WA) Department of Housing and Works Award for Public Architecture and one of eight 2007 RIBA International award winners, this building of a third place has provided the university with a new portal to learning and a new comfort zone.

Images by Patrick Bingham-Hall

Credits

- Project

- Edith Cowan University Library

- Architect

- JCY Architects and Urban Designers

Perth, WA, Australia

- Project Team

- Elisabetta Guj , Paul Jones, Paul Steed, Paul Aris, Melinda Payne, Moojan Kalbasi, Phay Hain Wei, Brent Aitkenhead, Alistair Ravenscroft, Rob Corker

- Consultants

-

Acoustics

Gabriels Environmental Design

Artist Anne Neil and Anne Farren

Builder Doric Group

Communications & lift consultant Wood & Grieve Engineers Perth

Data & security Norman Disney Young

Environmental consultant Gabriels Environmental Design

Fire engineer BCA Engineers

Landscape consultant Plan E

Library consultant Dr David Jones

Mechanical, electrical and hydraulic consultant Wood & Grieve Engineers Perth

Project manager Clifton Coney Group

Quantity surveyor Davis Langdon

Structural and civil engineer Maunsell Australia

- Site Details

-

Location

270 Joondalup Drive, Joondalup,

WA,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Education

- Client

-

Client name

Edith Cowan University, Architects Branch.

Website ecu.edu.au