Byron Bay is a complex place. For many Australians the name conjures up images of a slow-paced, hippie getaway with pristine beaches, clear blue skies and fibro surf shacks. They imagine healthy, almost spiritual-looking locals dressed in tie-dye clothes, wandering barefoot down the main street of this seaside village. That may well have been Byron in the 1970s, perhaps even early 1980s. Today’s Byron is somewhat different. The beaches remain breathtaking in their beauty. The spirit of a former era endures, despite increasing development and an ever-changing demographic. This still includes healthy-looking locals but now also a vast number of visitors, from overly tanned backpackers who arrive in cramped campervans to the uber-wealthy who fly in from around the globe (Gold Coast Airport is less than seventy kilometres away). Imagine the excitement of Shane Thompson, a surf lover with a soft spot for seaside towns, when he received a call from Peggy Flannery inviting his newly formed practice to participate in a design competition for a twenty-two-hectare resort on a ninety-hectare property with two kilometres of beachfront at Belongil Beach, just a few minutes from the centre of Byron Bay. Sound idyllic? Of course, but with every dream comes the complex reality of waking up.

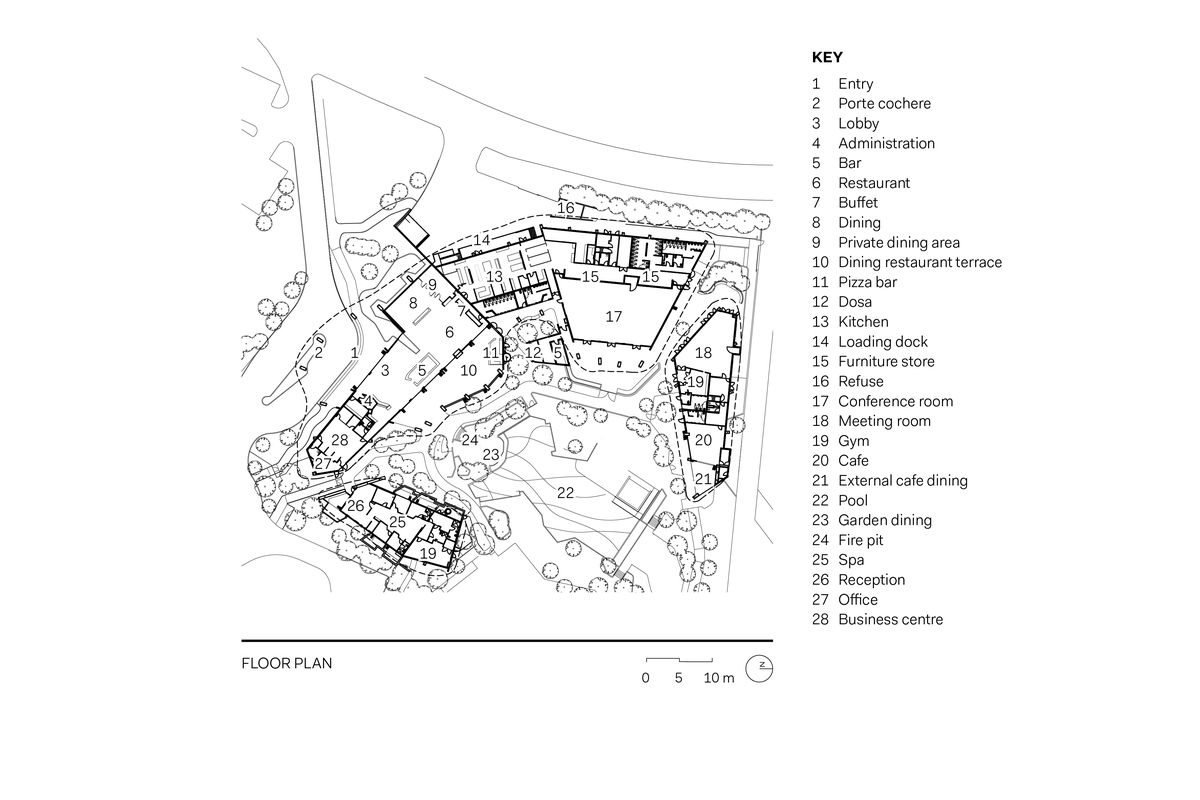

Many of the facilities at Elements of Byron are located in the main building, which sits at the northern end of the twenty-two-hectare resort.

Image: Dallas Nock

The complexities at Belongil were both logistical and political. The picturesque site is subject to flooding and bushfire attack, both of which can threaten building integrity, and it includes nineteen species of endangered wildlife. If the logistics were not complex enough, the political context was more severe. Byron Bay has an extremely active community who are not afraid to go into battle with the local council or developers to protect the environment in which they live. The site has a chequered history of failed development. In 1987 a small-scale resort of seventy-five cabins was approved but not fully completed. In the mid 1990s locals successfully won a Land and Environment Court case, which overturned an approval for a large Club Med facility. The next iteration, for 379 holiday units, was blocked by the NSW Minister for Planning in 2004, following an extensive community campaign. The same developer secured approval for 117 cabins in 2006 with a long list of conditions, which delayed construction. Construction was delayed further as a result of the 2008 financial crisis and the developer went into receivership in 2013.

Why is all this detail important? Suffice it to say it is important to reflect occasionally on the complex political environment within which architects operate, to contemplate those economic conditions that allow us to practise our craft as designers. The Flannerys’ team did their homework prior to the competition, using a loophole in the state planning policy. Their brief was to develop a new scheme as an “amendment” to the 1987 approval. A conference facility, pool, day spa, restaurant and bar, gym and multipurpose studio were to form a separate development application. All this work on finance took place long before the architects thought about form or function. Development director Jeremy Holmes notes that in addition to the pragmatics of program, the brief was for something “uniquely Byron … Peggy (Flannery) wanted something feminine … it had to be single-storey – the residents would accept nothing more.” He adds, “Shane’s sketches nailed it! There was no question.”

The hills and valleys of the nearby Tweed River area have informed many of the geometries of the project.

Image: Dallas Nock

Jeremy is primarily referring to the collection of curvaceous buildings that form the core of the development. While the multifarious process of detailed design of cabins, their locations and landscape was challenging, the strategy to adopt most of the 1987 configuration was predetermined. That said, the quality of the landscape and streets around the cabins should not be underestimated. The owner, operators (the complex now forms part of Sofitel’s international MGallery collection of high-end hotels) and architects rightfully acknowledge the significant contribution that the work of landscape architecture firm RPS Group makes to the quality of the environment. On the other hand, the design for the central core was open to interpretation. Thompson and his team proposed a cluster of neutral-toned buildings with daring double curved roof forms, arranged around the focal point of any resort – the pool. In a promotional video about the project, Thompson notes that in this space “you can see the arc of the sun in the sky uninterrupted by anything (else) artificial.” The space feels secluded, not only from the madding crowds of Byron Bay itself, but from the world. It opens to the north-east, with views to vegetated sand dunes in the distance, which provide one “wall” to the space. One feels both connected to and protected from the environment here.

Following my site visit at the facility, I later met with Shane Thompson. He explained the conceptual framework of the central space to me, starting with the idea of gathering around a campfire (there’s a gas fire pit between the bar and the pool), a tactic not unlike Gregory Burgess’s highly successful Brambuk Living Cultural Centre in Halls Gap, Victoria (1989). He continued the discussion of protected spaces and showed me an aerial view of nearby Mount Warning. Mount Warning, or “Wollumbin,” as it is known to the Bundjalung people, is the plug of the Tweed Volcano, some 23 million years old. The plug sits in the centre of a crater defined by a series of rugged ridges, an amazing landscape where one feels embraced by nature. The geometries of the hills and valleys carved by the Tweed River are not replicated in the project, nor does it feel like camping, but there is no doubt that the qualities Thompson has taken from these metaphors have informed the making of this key space.

One hundred and three cabins are scattered throughout the bushland, offered in several sizes and configurations.

Image: Christopher Frederick Jones

The double curved zinc roofs of the central building work particularly well in that one’s eye does not rest in any one spot for long as the ridge disappears in and out of view. The complex system of lightweight tubular steel trusses with post-tensioned cables within, combined with fibreglass composite purlins – by Murray Ellen of S-Squared – is the first of its kind in Australia. The client’s and architect’s commitment to getting this form “right” led to one contractor being terminated and delayed the opening of the project for several months – a brave economic decision. Such commitment is rare in this type of project, more often procured by corporations than by family businesses, who see a longer-term vision on their investment, once again demonstrating the precarious position of the architect in the creation of built form.

This project shows great sensitivity to its immediate environment in planning and execution. In the promotional material much is made of the inclusion of artworks by locals and the engagement of WetlandCare Australia, a not-for-profit company that manages parts of the property. Given this commitment, one might wonder why more active systems such as energy generation or blackwater recycling have not been included. The answer is probably not in the hands of the architect and is likely to be very complex.

Credits

- Project

- Elements of Byron

- Architect

- Shane Thompson Architects

Brisbane, Qld, Australia

- Project Team

- Shane Thompson,Tersius Maass, William Ellyett, Larissa Fouche, Jessica Hardwick, Arielle Ralph, Brionhy Ellyett, Milton Zietsman, Mark Donaghy, Amy Goodwin, Stacey Bellert

- Consultants

-

Certifier

Bennett Construction

Civil engineer Ardill Payne and Partners

Design manager Peggy Flannery (client)

Electrical engineer DBZ Designs

Interior design Coop Creative

Landscape architect RPS Group

Lighting designer Tony Dowthwaite Lighting Design

Services engineer EMF Griffiths

Structural engineer S-Squared (central facilities), Westera Partners (accommodation), Arup

Surveyor Bennett + Bennett

- Site Details

-

Location

Byron Bay,

NSW,

Australia

Site type Coastal

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Hospitality

Type Hotels / accommodation

Source

Project

Published online: 4 Aug 2017

Words:

John de Manincor

Images:

Christopher Frederick Jones,

Dallas Nock

Issue

Architecture Australia, January 2017