To the beach. Murrayfield Estate on Bruny Island, the setting for the 2010 Tasmanian Architectural Narratives.

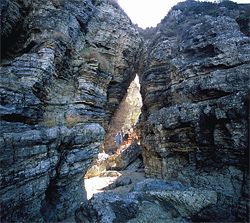

Looking through the headland.

The University of Tasmania’s Professor of Philosophy Jeff Malpas. Photograph David Travalia.

Symposium plenary on the beach.

Once every three years a quintessentially Tasmanian architectural event takes place. The place this time around was Murrayfield Estate, “offshore” on Bruny Island. While it may be called a symposium, the Tasmanian Architectural Narratives is colloquially known as A Weekend Away – an event that throughout its varied fifteen-year history has sought informal settings to encourage a familiarity in the exchange of ideas.

Occurring against the remarkable landscape setting of Murrayfield, this year’s event was attended by ninety delegates, including architects from within the state and from the mainland, and a sizeable contingent of students from the University of Tasmania. The delegate list also consisted of philosophers, artists and several of Australia’s notable authors.

Just as Louis Kahn says that a room affects what we say because we find ourselves already conditioned by built spaces, the natural world too solicits certain conversations. In Tasmania this idea is poignant, because here there seems to be a predilection towards place that is conditioned upon the formidable presence of the landscape. In his address at the weekend away, University of Tasmania’s Professor of Philosophy Jeff Malpas posited that attending to conditions of place is a matter of attending to our humanness. Arguing that architecture is about the making of places in which human beings can be most human, he said that “narrative and action are bound together, and narrative is always placed. We are not in places by looking at them. And as architecture is bound up with ‘placemaking’, our engagement with buildings is primarily found in the way that we act.” The act of architecture, as an engagement with the land and the environment, is therefore that which continues the conversation. Architecture is not about the narrative, but takes place as the narrative, and in doing so, makes places.

On the morning of the first day of the conference, in a small bay on the property’s eastern coastline, Rodney Dillon held a Welcome to Country. Dillon, a prominent member of Tasmania’s Indigenous community and Amnesty International Commissioner for Indigenous Rights, described the potency of this particular piece of land: “It is very important for us to be able to talk about our land – about our culture and our past. We have a responsibility to hand this down – unless you do that, the knowledge dies.” Bruce Chatwin in Songlines capture this sentiment when he wrote, “A country that isn’t sung is empty.”

Melbourne architect John Wardle, as a resident of Bruny Island, talked about working on his recently purchased property in one of the island’s northern bays. By transforming a historically significant heritage house into a family retreat that slips across the terrain, connecting the rooms with moments of repose against view and aspect, Wardle demonstrated the retention of the quality of the drawn line in the tectonic and eidetic aspects of his work, recalling Enric Miralles as a powerful influence. But this line drawn on the landscape is also one that connects Wardle to the community of Bruny Island: as a “resident” architect he has come to contribute significantly to local narratives through projects such as the design and construction of the community hall.

The weekend allowed delegates to contemplate deeper lines in the landscape. Murrayfield’s history is furrowed. This was part of Truganini’s country. It was here in 1832 that the missionary George Augustus Robinson struck an infamous accord with Truganini to encourage the North Eastern and Oyster Bay Tribes to abandon their traditional lands and relocate to Wybalenna Mission on Flinders Island. The moral consequences of Robinson’s ambition, the trust that was exploited and the tragedy that ensued are circles of relations that resonate deeply within Tasmanian’s attitude to the landscape. Murrayfield was handed back to the Indigenous community in 2001.

Brit Andresen, Professor of Architecture at the University of Queensland, spoke of the nature of the circle by describing the Indigenous initiation rings charted by Ludwig Leichhardt along the central eastern coastline of Australia as a mediating form between people and place. Andresen said, “In considering the making of circles, our previous gathering [at the Welcome to Country] exemplifies Alvar Aalto’s drawings of ancient Greek amphitheatres and atria. And by looking at the history of where people have gathered, Aalto is saying that such gathering can endure, because people gather in this way.”

There is something in the yarn around the circle of the campfire, or in the shadow of a vast angophora, or the compulsion to yell into a howling wind on a long stretch of coastline. This is a cultural tendency to equate words with spaces that perhaps connects to the way that Australia’s first peoples sang country and wove narratives across the continent. As architects, we make other narratives that are also passed down the generations. At the weekend away, Tasmanian practitioner Paddy Dorney delivered a mindful narrative around the memory of his father James Esmond Dorney, whose tectonically refined work from the 1950s and 1960s continues to evade any wider publication. Architects make narratives for the future, as when James Wilson, co-director of the practice Room 11, speculated about the population growth trends and the extent to which Tasmania’s topography might cope with increased development, through a proposal of a vast land bridge to the mainland, a project which is part of Now + When, Australia’s contribution to the 2010 Venice Biennale.

The narratives continued over dinner, served on a single long curved line of tables drawn through the centre of the shearing shed. Under candlelight, and over slow-cooked mutton, grown and slaughtered on Murrayfield, Richard Leplastrier described his circumstances of working with Jørn Utzon on his unrealized house at Bayview. Leplastrier served as a tangible link to Utzon’s genius as he ruminated on detailed working drawings, expressing the considered articulation of three pavilions on a sandstone headland.

The symposium plenary on the second day was facilitated by Honours students in the Masters of Architecture program of the University of Tasmania and coordinated by Mathew Hinds and Stephen Loo. Students engaged delegates in conversations on issues of identity, memory, site and place. The plenary was given circumstance by Tasmania’s eminent author and commentator Richard Flanagan, who took the delegates on a walk to a remote part of Bruny Island, precariously traversing a wave-battered shelf and culminating at a small shack buried in the lee of the dune and salvaged from a shipwreck late last century. Flanagan’s narrative contribution was visceral in lieu of a spoken one.

It is often said that issues of place, culture, identity and landscape have become predestined themes of conversation for the fraternity in Tasmania. Perhaps this is due to the tendency for the natural landscape to anchor the creative voice. Or, to say this more accurately, the landscape provides the potential for architectural narratives to take place, affording the profound realization of place. A Weekend Away has always tended to be such an occasion.

Mathew Hinds is an associate lecturer, and Dr Stephen Loo is Professor and Head of School of Architecture and Design at the University of Tasmania.