David McGlashan’s Heide II is the site of a recent exhibition which considers the house in relation to other houses by McGlashan and Everist. Review by Hannah Lewi.

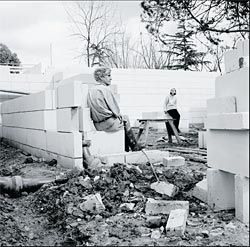

John and Sunday Reed at the construction site of the Reed House (Heide II), Bulleen, 1966. Photograph Nigel Buesst.

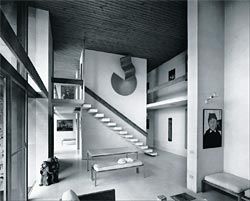

Heide II living room facing east, 1968. Gelatin silver print. Photograph Wolfgang Sievers.

A short film playing in the Heide II study, newly opened to the public, with the views to the garden.

Overview of the Heide II living room, showing the installed exhibition. Photographs John Brash.

To mark the twenty-fifth anniversary of Heide and its re-opening after extensive additions, the museum is showing a modest yet finely conceived exhibition on the architecture of Heide II. This was the second house of John and Sunday Reed to be built on the site of the present Heide Museum of Modern Art in Melbourne.

It was designed by David McGlashan and completed in 1967. The exhibition and catalogue Living in Landscape, guest curated by Philip Goad, considers Heide II in the context of a series of houses by the partnership of McGlashan and Everist in the 1960s. The current show fits within Heide Museum of Modern Art’s ongoing brief to promote design and architecture alongside the visual arts through its exhibitions, events, publications and facilities. This willingness to both patronize and exhibit modern and contemporary architecture is rare in Australia, where most galleries see architecture as lacking in public appeal.

The accompanying catalogue is a handsome publication in the model of a number of other small book catalogues on modern Australian architecture. The motif of the plan of Heide II is elegantly indicated on the catalogue’s front cover, and its analysis continues throughout the publication. For example, it is compared to Mies van der Rohe’s brick country house project (1924) and Theo van Doesburg’s painting Rhythm of a Russian Dance (1918).

The informative essays by Philip Goad and Judith Trimble are complemented by carefully chosen archival images and architectural drawings of exemplar houses.

The essays are book-ended by a foreword by Neil Everist and a biographical summary of the partnership. The catalogue is an admirable and timely addition to the documentation of mid-century Australian architecture.

In seeking influences and resemblances, both Goad and Trimble discuss Heide II and the partnership’s domestic work within the international context of post-WW II Modernism. They particularly emphasize the influence of American domestic architecture by the likes of Larrabee Barnes, Johansen and Neutra. Yet these precedents are inflected by uniquely antipodean situations: the house in the bush, the suburb, the beach. As a previous review of Heide II by Neil Clerehan aptly described: “It is International Style set down amongst the melaleucas.” ›› These inflections are evident in many elements of Heide II, but perhaps most evocatively in the enfolding walls: Miesian-inspired planes turn in on themselves to become U-shaped and are reconfigured in massive Mount Gambier limestone to create a series of labyrinthine rooms. This same device extends outside to form gardened courtyards, but the threshold between inside and out is different to, say, Neutra’s fully glazed window-walls. For example, Sylvia Lavin, in her 2004 book Form Follows Libido, depicts Neutra’s Kaufmann house as “leaking amorphously beyond its physical perimeter through expansive window-walls and seeks atmospheric continuity with its environment through indoor/outdoor heating, materials and programme.”1 Heide II, in contrast, creates a more protective, even fortress-like relationship with its bush prospect. Although Living in Landscape describes the architecture of McGlashan and Everist as one of framing, embracing and enhancing natural settings, and Trimble’s essay poetically evokes the act of place-making as central to the practice, the reader is left feeling that the specific landscape of the Heide grounds is a little absent from the catalogue analysis.

Perhaps it could have been augmented by a short essay devoted to the rich history of the native and exotic gardens created by the Reeds.

The simply mounted and hung exhibition of photographs and drawings works well within the rooms of the house. Three short films, including an interview with McGlashan from the late sixties, play in the bedroom that has now been opened up to public access. Careful curation and interpretation evoke the presence of the Reeds’ time spent living in the house.

For example, a series of small interpretive panels, written especially for this exhibition, explain the functions of the rooms and layout. Original furniture has been restored and displayed, and a number of paintings and objects from the Reeds’ collection have been placed exactly as they are depicted in original photographs by Wolfgang Sievers. These photographs, along with those by Nigel Buesst of Heide II under construction, document the close involvement of John and particularly Sunday Reed throughout the design and construction process and their occupation of the house as a home. The images consciously attempt to furnish the otherwise stark spaces of the house with, for example, a figure reading, the dog Go-Go, and familiar objects such as the spectacles left on the desk next to the typewriter and books in the snuggery. Like the oft-reproduced photographs of the interiors of the Villa Savoye – so carefully orchestrated by Corbusier – these images imply and reassure of livability in an architectural space that otherwise offers few hints of domestication.

The original brief for Heide II had a hybrid function, to serve both as a private house and a gallery. This inherent ambiguity of the Modern house as gallery and/or home is amplified by the staging of this exhibition. The show transforms the house into the primary exhibit of itself rather than merely a container of exhibitions. And although not strictly classed as a “house museum” (as defined by a conference on the subject in Genoa in 1997), Heide II in this role follows in the tradition of other modern foundations and public display houses – think of the Le Corbusier Foundation in the Villa La Roche in Paris, the Willow Road House by Erno Goldfinger in Hampstead, and the Schröder-Schrader House in Utrecht; or closer to home, the Rose Seidler House in Sydney and perhaps, in the future, the Walsh Street Boyd house in Melbourne.

They are all testament to the importance of the house as a testing ground for the development of Modernism.DR HANNAH LEWI IS A SENIOR LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF MELBOURNE AND IS PRESIDENT OF THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS, AUSTRALIA AND NEW ZEALAND (SAHANZ).