A RECENT EXHIBITION OF ‘STITCHED’ DIGITAL PHOTOGRAPHS BY ALISON BENNETT GIVES CHARLES RICE AN OPPORTUNITY TO CONSIDER INHABITATION AS AN ONGOING PROCESS OF NEGOTIATION AND THE INTERIOR AS BOTH IMAGE AND SPACE.

Modern kettle and outmoded stove in the Ackermann Cottage kitchen suggest inhabitation as a negotiation between ‘then’ and ‘now’.

The English Group, the dissolution of the interior.

La Paloma music room, stereo system in a ‘period’ room.

The ‘frozen’ interior of the office at Craigmoor House, set up as a house museum.

OUR CONTEMPORARY image-saturated culture revolves around our homes. Sitting comfortably in our interiors, we are constantly offered images of how we should live our domestic lives, or how others live theirs – this correlation between images of the domestic and the domestic setting of their consumption is at the core of our contemporary fascination with lifestyle. And as a society, we seem at ease with the close fit between mechanisms of publicity and the private sphere. Yet this is not just a contemporary quirk. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, bourgeois society began to experience the domestic interior as a particular kind of spatial condition, and also as a condition equally based in the visual. In short, they understood the interior to mean both a space and an image of a space.

This idea of the interior as a particular kind of relation between the imagistic and the spatial is given new impetus in Inside Hill End, a series of photographs by Alison Bennett recently exhibited at The Mint in Sydney. These depict various interiors from the historic New South Wales town of Hill End. Bennett began her project with an interest in how various myths circulate through and about the town. Coupled with these myths is the ageing physical reality of the town’s built fabric. Hill End is a relic of the nineteenth century – in 1872 it was a centre for goldmining and had a population of around 8,000. Currently it is home to only 120 people, Bennett among them.

Bennett dealt with this complex context by experimenting with the technical possibilities afforded by digital photography. Each image of an interior is a panorama generated from the combination of individual frames. Yet what would normally be shown as an abrupt shift of view and change of focus has been rendered seamless by carefully smoothing together these individual frames. Only the ragged edge identifying each frame gives a clue to this composite construction. The space of a particular interior unfolds along the length of each panorama, and the viewer quickly becomes aware that these images do not map easily onto their spatial counterparts: taking in a panorama as a single image presents an impossible, warped view of the interior pictured. As such, the panoramas offer a double of the spatial interiors, rather than a transparent window onto them. In effect, they construct the interiors anew on the elongated image surface, and offer the viewer an insight into the tension that exists at Hill End between the historical and the contemporary.

Several images show interiors that are currently inhabited but that also retain their sense of being nineteenth-century relics. There is a frisson in the juxtaposition of a modern kettle and an outmoded stove, or a stereo system sitting discretely within what appears on first glance to be a “period” room. This frisson allows the viewer to understand inhabitation for these residents as a continual negotiation between now and “back then”. In this regard it is interesting to measure these inhabited interiors against those of Craigmoor House, which has been conserved in Hill End as a house museum. In attempting to present “the way these people actually lived in the past”, the Craigmoor House interiors seem to deny any sense that, even “back then”, inhabitation was a negotiation with an existing physical and social fabric.

These interiors come across as simply frozen in the past.

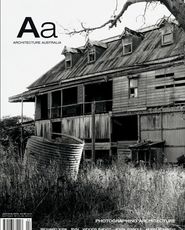

The exhibition also includes images of several derelict structures. These are unsettling because they picture the complete dissolution of the interior. They show precisely the difference between an interior and the inside of a building. In their picturing of decay, these images index the passing of a certain mode of inhabitation, the mode that Craigmoor House seeks to preserve. But the derelict structures are in some senses truer to the intent of a museum like Craigmoor House – they demonstrate in an affecting way that inhabitation is about constantly needing to make and remake an interior, rather than simply assuming it as given, as both fixed in time and timeless.

Throughout the exhibition, I had the sense that a pervasive image of the nineteenth century must haunt the current inhabitants of Hill End, and that this image dominates how they negotiate their inhabitations – much in the way that a home improvement show might induce us to look critically at our own interiors. Most photographs of interiors do not present inhabitation as contested in this way. Acting more like windows, they encourage us to see interiors as static spaces, existing some time in the past, or as the pristine result of an up-to-the-minute makeover. In contrast, Bennett’s panoramic images prompt us to see the interior from a literally impossible perspective. It is, however, a perspective that allows us to investigate how the spatial and the imagistic, the contemporary and the historical, interact in the continual negotiations of inhabitation. Such an estranging perspective is relevant for considering both domestic conditions burdened by history, as at Hill End, and domestic conditions that are prey to idealized images of domesticity, whether fed by television, coffee-table books or magazines.

DR CHARLES RICE IS A LECTURER IN ARCHITECTURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES.