Perry Lakes Stadium scoreboard in 2003.

A Games Village house, designed by Peter Maidment, in its present condition. Photographs Tony Nathan.

Competition drawing for a Type B House by Silver Fairbrother and Associates.

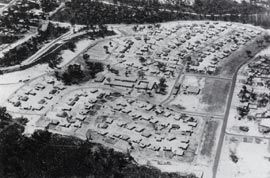

Overview of the Games Village site, 1962.

Games Village, 1962, with houses by Silver Fairbrother and Associates.

Perry Lakes Stadium in 2003. Photograph Tony Nathan.

MODEST IN SCOPE and execution, Fading Events and Places: The architecture of the VIIth British Empire and Commonwealth Games Village and Perry Lakes Stadium documents the architecture of a period when Perth, as a city, was lively with ambition and confidence.

Despite (or perhaps because of) this modesty, the exhibition does more than simply document a group of lost or decaying buildings. It has a wider significance for Western Australia’s urban history – functioning both as a spur for the continuing public rehabilitation of postwar WA Modernism and as an important reminder of its consequences for Perth’s contemporary suburban form.

The hosting of the 1962 Commonwealth Games fostered a growing sense of civic confidence. Building upon a burgeoning economy and significant metropolitan growth, it inspired a vision of Perth as a progressive, modern city of international significance. A number of architectural projects were undertaken to provide facilities for the games, some of which – Beatty Park Aquatic Centre for example – remain icons in Perth’s suburban landscape.

Although it acknowledges this wider activity, and includes material documenting Perry Lakes Stadium, the exhibition’s focus is firmly on the Games Village.

A unique project, the village was a model suburb developed by the State Housing Commission to accommodate visiting athletes, which was then sold into private ownership after the games. The subdivision and housing designs were the subject of competitions, the result being a suburb that stood in stark contrast to standard subdivision and building practice of the time. The village has probably been the most enduring legacy of the Games’ building programme, its innovative designs and layout are now familiar, timeworn elements of Perth’s urban fabric.

The fondness with which the history of these houses is recalled in Perth suggests that a sympathetic reading, by the broader public, of Modernism’s contribution to the city’s built environment is possible. And that such a reading might begin to counter the orthodox conception of Modernism as the rape and pillage of our pre-war building stock (a position exemplified by the previous State Government’s desire to demolish the 1962 Perth Council Offices because they were inconsistent with a planned CBD “heritage” precinct).

It is also timely that the planning and design of the village be revisited in light of current concerns about Perth’s urban future. The current State Government has recently sought feedback on the future of Perth’s metropolitan region from the public, community and industry groups. The most ambitious element of the process, labelled “Dialogue with the City”, was a forum for 1300 participants in September. The aim was to give the public insight into planning issues and processes while also determining community attitudes to the control of growth in the metropolitan region. Participants had to grapple with the inherent unsustainability, and ramifications, of the city’s rapidly expanding, low-density, car-dominated landscape.

This current dispersed, suburban character is strongly grounded in the planning and architectural models exemplified by the Games Village. Along with its architecture, the urban form of the village was very much influenced by postwar British Modernism; the attempts to transpose its formal qualities being modulated by a strong, underlying local inclination towards the picturesque garden suburb. Fading Events and Places provides an extremely apt stimulus for discussion of Perth’s future because, although a unique development, the village consolidated many elements that would become familiar features of the modern Perth suburb.

The desires of the local architectural profession to provide a blueprint for modern housing production (in a similar manner to the Californian Case Study Houses) were largely unfulfilled, but many aspects of the project would later be more prominently used in residential subdivision: wide lot frontages, living areas focused on the television, greater connection between interior and exterior living areas, standardized components, raft slabs, glazing in unit joinery et cetera. While the formal aesthetics of this local architectural modernism were not widely assimilated, the overarching environmental form represented a successful translation of the properties of the garden suburb within the bounds of post-war planning. The village was a testing ground, and the character of Perth’s contemporary suburbs was latent in its configuration.

In describing the character and significance of the village and stadium, the exhibition is primarily focused upon the architecture; this is the element disappearing from Perth’s landscape. Thus, in the knowledge that Perry Lakes Stadium is slated for demolition, and the village houses are also slowly disappearing, the documentary material is particularly poignant.

Competition drawings for the houses have been reproduced, (many featuring charming hand rendered perspectives), models have been built of the houses, news photos from the Games period and residents’ images of their own houses are part of a projection loop, and a photographic essay commissioned from local photographer Tony Nathan captures the current condition of the buildings.

The aims of curators Hannah Lewi and Stephen Neille – to provide a nuanced, affectionate documentation of these places; one that might juxtapose the idealized places and the actual – are served well by the range of material they have assembled. The catalogue also provides excellent contextualization of this imagery through a number of essays. Appropriately, on opening night they were effectively upstaged by the subject itself. Launching the exhibition in the Perry Lakes Stadium control room, a cold, wet night in Perth only served to accentuate the melancholic atmosphere in the deserted stadium. Inside, the weather encouraged clouds of mosquitoes to emerge, dancing around the broken light fittings and flitting across the decaying aluminium window sections.

LEE STICKELLS IS A GRADUATE ARCHITECT AND URBAN DESIGNER WORKING FOR WOODS BAGOT, PERTH. HE IS ALSO COMPLETING A PHD AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA. CURATED BY HANNAH LEWI AND STEPHEN NEILLE, WITH PHOTOGRAPHS BY TONY NATHAN, THE EXHIBITION WAS PRE