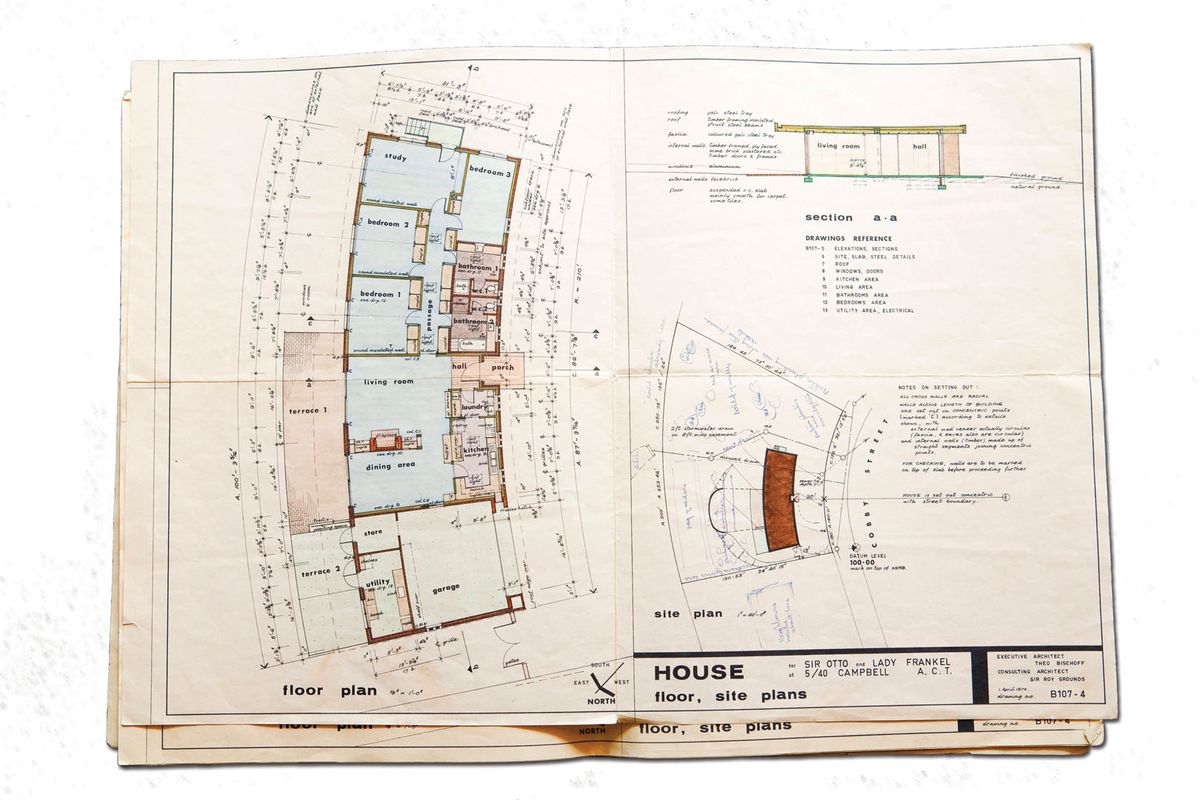

Sir Roy Grounds (1905–1981) completed a house in 1970 for Sir Otto and Lady Margaret Frankel, in the Canberra suburb of Campbell. Positioned on an unusually large 2,900 square-metre block on the highest street in the district, the comparatively modest house sits at the meeting of Canberra’s urban edge and the bush. On its front side, several streets of houses merge into the Australian War Memorial district and on to the city centre, Lake Burley Griffin and across to the Parliamentary Triangle. At its back, untamed bush extends to the top of Mount Ainslie, one of the key axial markers for the designed capital city. Echidnas sometimes visit the urban-bush intersection occupied by the Frankel House, while kangaroos frequently raid the vegetable garden or roam across the open block to graze incongruously in the carefully tended flower gardens of neighbouring houses.

The choice of Grounds as architect was not by chance. Sir Otto probably met Grounds when the architect was working on the design of the Australian Academy of Science in Canberra. The Frankels, who were supporters of arts and music and important collectors of contemporary ceramics, commissioned Grounds to design a house to accommodate those interests. Display areas were designed into the main rooms to hold works such as those by Japanese master potters Shoji Hamada and Tatsuzo Shimaoka and renowned potters Hans Coper and Lucie Rie (much of the Frankel ceramic collection is now housed at the National Gallery of Australia). Lady Frankel was interested in making as well as collecting ceramics and turned the utility room into a small pottery.

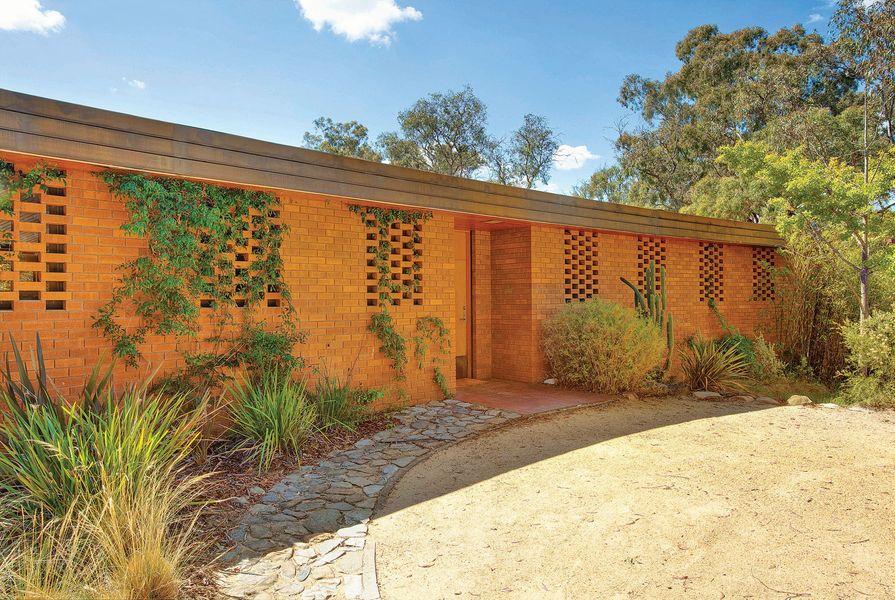

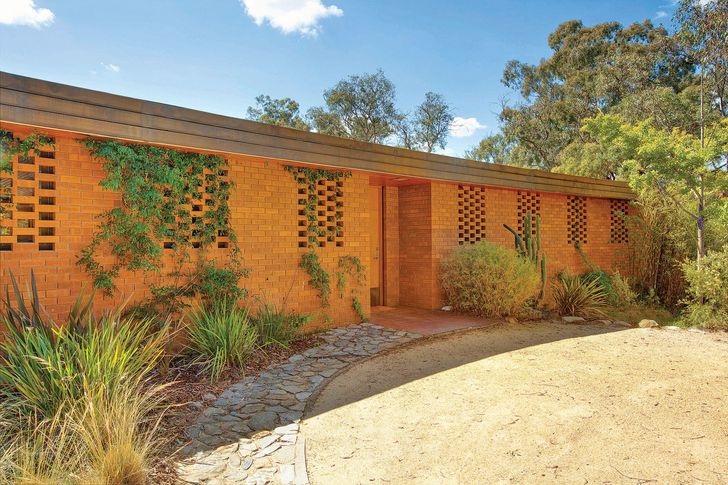

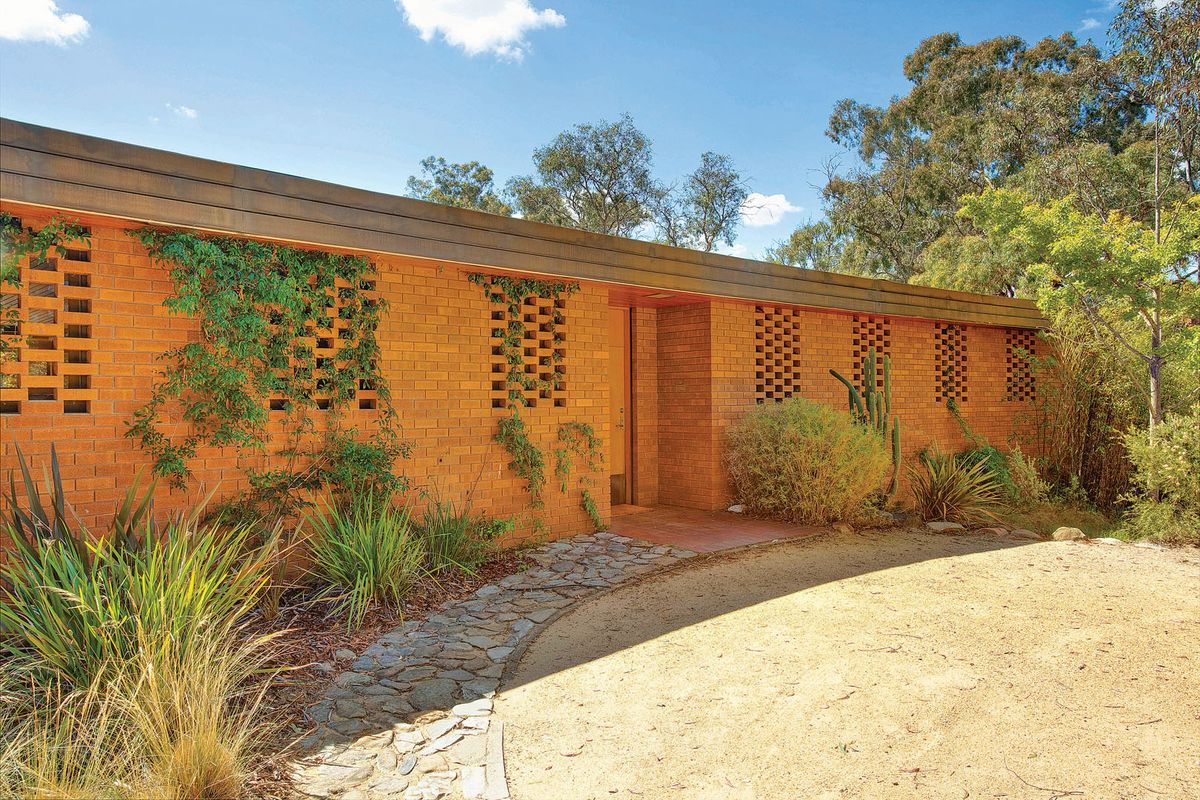

The terse facade with brick-screened window openings was explored earlier by Grounds in his design of Melbourne’s NGV.

Image: Neil Fenelon

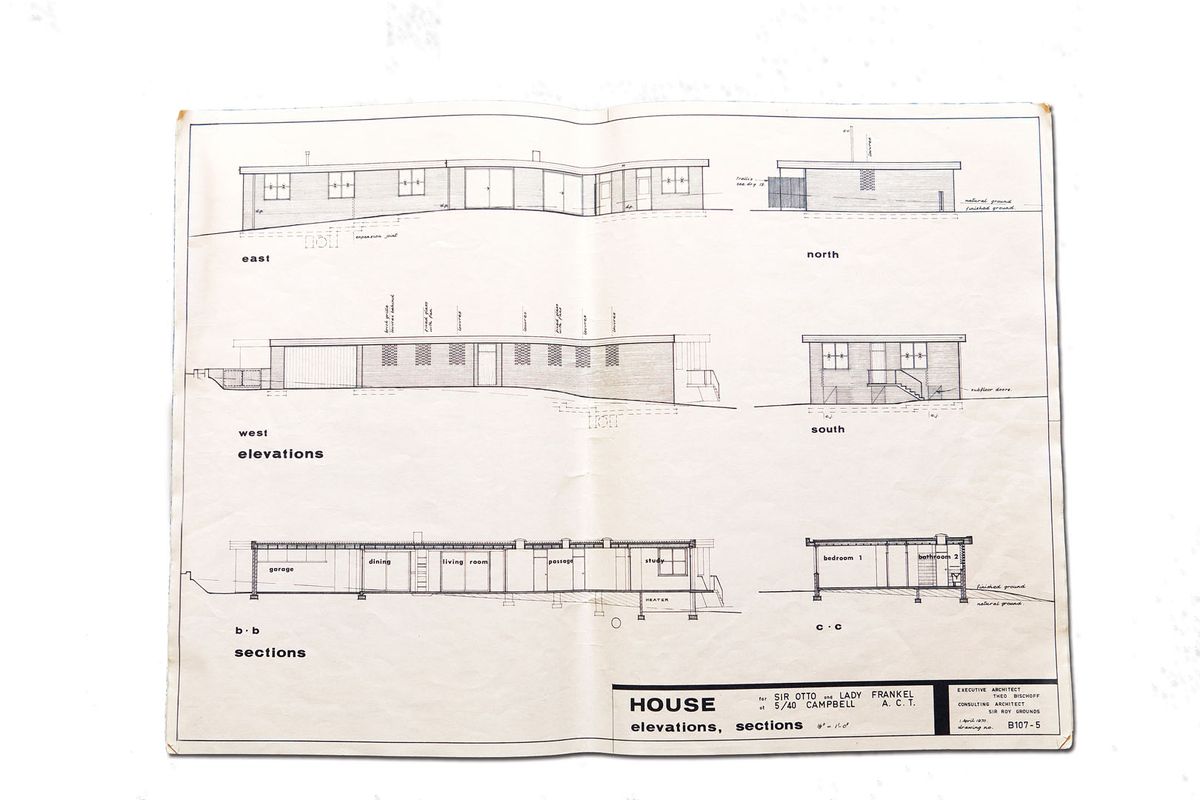

The Frankel House is shaped in a slight curve, aligned to the curve of the street. Set back in an informal native garden, the house presents a terse brick facade to the passer-by. A single recessed central opening is punctuated on either side by unrevealing brick-screened window openings. Grounds had recently explored this structural theme on a larger scale. His then newly completed National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne similarly presented a stern Victorian bluestone street face, punctuated by a single opening into a finely constructed interior.

The Frankel House exterior recalls the reserved facades of Jørn Utzon’s 1959–62 housing development at Fredensborg, Denmark, which had been widely publicized in Australia. In each project, Grounds and Utzon expressed a synthesis of Scandinavian and Japanese references in their spatial order, extensive use of timber and sensitively crafted materiality. Neither architect’s somewhat brusque exterior strategy suggested the serenity of the wood-lined interior contained within. These houses are like oysters, with unprepossessing exteriors shielding something surprisingly lustrous.

At the Frankel House, smooth brick paving flows without interruption from outside to a small entrance hall, firmly grounding the building in the landscape. Enclosure of the entrance hall suggests a Japanese genkan, the transitional space for greetings and the removal of shoes before stepping onto a different floor surface, tatami mats or carpet.

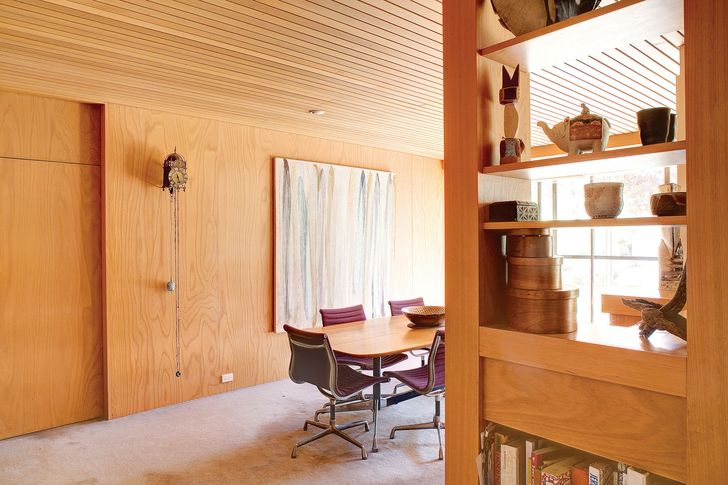

Like many Japanese homes, especially in Kyoto, there is a clear separation of the internal public and private areas. Grounds’ spatial sequencing is carefully orchestrated, with clear separation of public and private spaces to meet specific requirements of the client. To the left of the entrance hall, a door connects unobtrusively to a storage area and kitchen, while straight ahead are the formal living and dining rooms with their views to the courtyard and bush. To the right, a sliding panel door opens to private rooms along a hallway spine. Three bedrooms with built-in storage and two bathrooms are arranged at the sides of the curved hallway, which is lined with additional “invisible” storage units in the manner of Japanese dwellings. Elsewhere Scandinavian references can be identified, including the treatment of ceilings, which are lined with timber in a manner reminiscent of Alvar Aalto’s 1937 Villa Mairea.

Scandinavian references include timber-lined ceilings, reminiscent of Alvar Aalto’s 1937–39 Villa Mairea. Artwork: David Rankin, Mask for Liang Ki, 1972.

Image: Neil Fenelon

A large study at the end of the hallway has a wall of built-in bookshelves and a separate external entrance. It now serves as a design studio and music room, with lovely acoustics for the grand piano. Future mobility requirements for the owners were specifically anticipated in Grounds’ design. There are no internal changes of level, transitions from inside to outside are without raised doorsills, the bathrooms are accessible, and door openings are sufficient to accommodate a wheelchair.

The living and dining spaces are separated from each other by a fireplace anchored between shelves.

Image: Neil Fenelon

In the “public” end of the house, the low-ceilinged living and dining areas are separated by a central brick fireplace, an “axis mundi,” anchored between half-height wood shelves and storage cupboards. Both rooms have full-width sliding glass doors that open into a brick-paved courtyard garden, with the later addition of a trellised dining area and low rectangular fishpond against a long retaining wall. The view continues up the slope to a row of fruit trees and the tall eucalypts populating the bush setting of Mount Ainslie beyond.

The kitchen is generously fitted with built-in storage, all smooth-timber-faced as in the rest of the house. Sir Otto reportedly preferred to have the workings of the kitchen fully screened from view. Although Grounds provided a convenient counter extending from the kitchen through to the dining room, its vertical sliding wood screen remained firmly closed during the Frankels’ occupation. The screen now remains open, providing a convivial social connection between the kitchen and family or guests gathered in the adjacent dining room.

One of several Grounds-designed houses in the suburb of Campbell, the Frankel House is among the most intact and sensitively updated. Since 1999 the house has been owned by Professor Stephen Frith, former head of architecture at the University of Canberra, and his wife, ceramic artist Catherine Reid (who now uses Lady Frankel’s pottery to make ceramics for exhibitions). They have updated the kitchen and bathrooms with careful insertions of more contemporary fixtures while remaining true to the integrity of the house and its fine-quality craftsmanship. The brown carpet (popular in the 1970s) was replaced with a charcoal-coloured carpet, while the kitchen cork tiles and bathroom brick flooring have been retained. Window treatments, originally in colourful 1970s patterns, are now cream-coloured Roman blinds. Lighting has been modernized with a combination of carefully selected commercial fixtures and porcelain lights individually designed and made by Catherine. The timber interior has been entirely retained and despite the passing of several decades, the house still exudes a delicate fragrance of wood.

This review of the Frankel House is part of the Houses Revisited series.

Credits

- Project

- Frankel House

- Architect

- Roy Grounds

- Site Details

-

Location

Campbell,

Canberra,

ACT,

Australia

Site type Suburban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

- Client

-

Client name

Sir Otto and Lady Margaret Frankel

Source

Project

Published online: 27 Jan 2014

Words:

Eugenie Keefer Bell

Images:

Neil Fenelon

Issue

Houses, October 2013