“Twenty foot of solid steel. Will last a lifetime. Second-hand and slightly salt-stained, but that’s what gives it character. Fully fitted, ready to use; just add water and gas (bottle) and you’re ready to go. Only $30,000 on the road, but we can do something on the price if you buy in bulk.”

Future Shack. I’m sold. Buying a house is as easy as buying a car – and cheap!

Whether or not one conjures up images (or voices) from sales pitches, miracle cures or labour-saving devices, there’s something quite extraordinary about one’s first encounter with Future Shack. Despite its current location in a goods yard behind a light industrial unit in Flemington where it was fabricated, I could see it on my bit of sand dune in Gippsland. I want one. My colleague could imagine getting old in one at the back of his garden in Clifton Hill. Although memories of holidays at the beach may be evoked, Godsell’s agenda is serious. This is an architecture that addresses needs rather than desires. But like most good projects it does both.

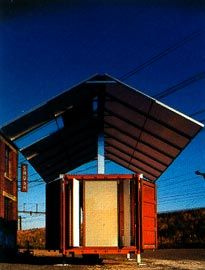

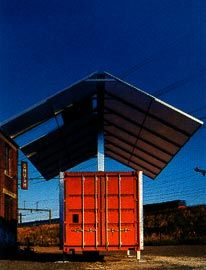

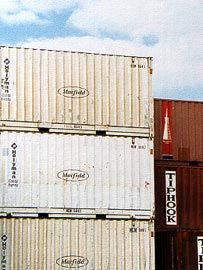

Future Shack is the prototype for mass-produced, relocatable emergency and relief housing. The house has applications for a variety of needs – post flood, fire, earthquake, typhoon, or similar natural disasters; temporary housing; third world housing; remote housing. The main volume of the building is a recycled 20-foot shipping container, a universal module that is mass-produced and inexpensive, robust and durable. As a basic unit the container can be stockpiled for use as required by aid-coordination agencies, or in locations prone to disaster. It is designed to be shipped, and is easily transported by road and rail. All infrastructure for handing the module is available throughout the world.

The unit is totally self-contained. Packed inside are water tanks, solar power cells, access ramp, roof ladder, parasol roof and supporting structure. A satellite receiver and external light bracket act to brace the glass interior doors in transit. The container itself has had minimal exterior changes – several additional slots to accept the structure, a top-hinged front opening for the entrance, and a series of operable panels in the roof for ventilation – but nothing detracts from either its seaworthiness or its ability to be stacked or handled identically to its unmodified kind. It remains a container conceptually to Godsell. The clean skin of the interior is packed with his tools for re-habitation, along with, one might expect, additional clothing, food and blankets for the dispossessed.

Future Shack can be fully erected in 24 hours. A pair of steel brackets with telescoping legs is fixed to the outside of the container, which is located onto the site by standard truck or rail-mounted lifting gear. Site levels are established and the legs are pinned into position. Pivoting broad steel plates at the base of the legs eliminate the need for footings; thus little site preparation is necessary. Uneven terrain and slopes up to 45 degrees can be accommodated. All fixings are simple mechanisms, requiring basic tools and skills, and little maintenance for remote locales. The building is thereafter totally self-sustainable, capable of generating electricity, and with communications, thermal insulation to R4.0, a shading co-efficient of 0.49, and natural ventilation. The technology responds to the assessment and resolution of the appropriateness for the task, not to slight-of-hand detailing designed to impress.

It could be said that we’ve seen it all before. Warren Chalk’s houses “flew” in the early days of Archigram: a container suspended from a helicopter is a more compelling image than one transported by a basic truck. Others might cite existing container communities such as the mining camps in Brunei and question the need for an architect’s involvement where ad-hoc initiatives already exist. Caravans and portable structures have worked fairly well thus far on many remote sites. An engineer’s response to the issues raised by Godsell might be to minimise erection schedules with inbuilt hydraulics and integrated structural systems to avoid lifting gear. Future Shack however is different. It is significant that it is built. (Godsell self-funded the prototype that has been on his drawing board since 1985.) And it is clearly the work of an architect – one attempting to satisfy a social need as opposed to an immediate problem.

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the parasol roof which shades the container and protects the water supply and outdoor space. For Godsell the pitch provides the “universal symbol of home”, and, surprisingly enough, he’s right. (The roof is easily adapted to local versions of “home” with its galvanised steel frame designed to accept thatch, mud and stick, palm fronds, etc.) Any fears of the oppressive nature of the container are allayed – the minimal floor area (15 square metres), the heat, the repetitiveness of the module – this project is not a compromise, or an excuse. One can imagine the containers multiplied as communities in various landscapes – as hill towns, or protecting each other on wind-swept plains – instead of as bleak tracts of repetitive elements. Laid end to end, large dining halls can be formed; side-by-side, families become reunited. Peter Pragnell would call this a “friendly object”.

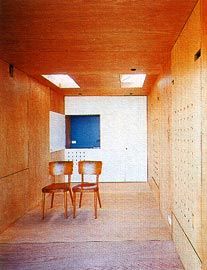

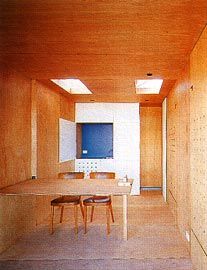

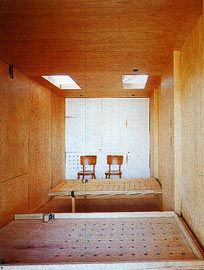

The project’s history runs in parallel with Godsell’s series of award winning single-family houses. Their research agendas have been complementary: inexpensive manufacturing and construction methods, the prototype, environmental concerns, and the continuing search for the appropriate dwelling. The Godsell House II at Kew demonstrates that volumetric clarity offers possibilities for complexity and richness in everyday life; his long table, strategically positioned in the space, supports and encourages a wide range of activities and rituals, above and beyond a deterministic overlay of program. In Future Shack, the butt-jointed marine plywood-lined interior (first tested in the packing crate walls in the MacSween House) is conspicuously clear of the clever single-program miniatures of the conventional family house such as those found in a caravan. A table and two beds are hidden within the lining of the steel shell and pulled down when needed; the kitchen and bathroom are compact and gimmick-free.

Godsell’s developed planning and circulation strategies have a subtle presence in Future Shack: the altered perceptions of size and scale created by the corridor (Godsell House I); storage walls as room dividers (Godsell House II); the integrity of interior spaces reinforced by strategically located openings (Carter/Tucker House).

From the entrance ramp one sees straight through the glass doors (or screen, depending on climate) and on through the pivot-hinged opening behind the steel doors at the rear. The hydraulic door to the container defines and shades a front “verandah” created by the ramp. A series of interior spaces is articulated along the long axis at the container’s edge. Subtle plan shifts determined by the furniture define different qualities of space: views and access through the room are unobstructed when the table is in position; when the beds are down the notional corridor is blocked, promoting a sense of containment. The bathroom and kitchen are housed in the thickened walls that run perpendicular to the axis. The container, albeit small, is packed full of architecture, both in design and ideals.

Colleagues in typhoon and earthquake-prone Taiwan have quite understandably embraced this project and concur with Godsell’s statement: “As architects in stable democracies our responsibilities are reasonably clear cut. Our role in those societies where freedom has been ripped away by force, or where nature has devastated whole cities, or when generations of minority groups have been forced into a life of poverty because of a political philosophy, is hazy by comparison. The need ‘to house’… offers architects the opportunity to provide shelter for fellow human beings in need.”

Sand Helsel wrote this review in Taiwan during a typhoon.

Photography by Earl Carter

Credits

- Project

- Future Shack

- Architect

- Sean Godsell Architects

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Builder

RD McGowan Building

Steel fabrication Shush Metal Products

- Site Details

- Project Details

-

Category

Residential

Type New houses

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Sep 2001

Words:

Sand Helsel

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2001