Citation from the Jury

Glenn Murcutt is a modernist, a naturalist, an environmentalist, a humanist, an economist and ecologist encompassing all of these distinguished qualities in his practice as a dedicated architect who works alone from concept to realization of his projects in his native Australia. Although his works have sometimes been described as a synthesis of Mies van der Rohe and the native Australian wool shed, his many satisfied clients and the scores more who are waiting in line for his services are endorsement enough that his houses are unique, satisfying solutions.

Generally, he eschews large projects which would require him to expand his practice, and give up the personal attention to detail that he can now give to each and every project. His is an architecture of place, architecture that responds to the landscape and to the climate.

His houses are fine tuned to the land and the weather. He uses a variety of materials, from metal to wood to glass, stone, brick and concrete – always selected with a consciousness of the amount of energy it took to produce the materials in the first place.

He uses light, water, wind, the sun, the moon in working out the details of how a house will work – how it will respond to its environment.

His structures are said to float above the landscape, or in the words of the Aboriginal people of Western Australia that he is fond of quoting, they “touch the earth lightly.” Glenn Murcutt’s structures augment their significance at each stage of inquiry.

One of Murcutt’s favorite quotations is from Henry David Thoreau, who was also a favorite of his father: “Since most of us spend our lives doing ordinary tasks, the most important thing is to carry them out extraordinarily well.” With the awarding of the 2002 Pritzker Architecture Prize, the jury finds that Glenn Murcutt is more than living up to that adage.

The Pritzker jury for 2002 was J. Carter Brown (chair), Giovanni Agnelli, Ada Louise Huxtable, Carlos Jimenez, Jorge Silvetti and The Lord Rothschild.

“The architecture of Glenn Murcutt surprises first, and engages immediately after because of its absolute clarity and precise simplicity – a type of clarity that soon proves to be neither simplistic nor complacent, but inspiringly dense, energizing and optimistic. His architecture is crisp, marked and impregnated by the unique landscape and by the light that defines the fabulous, far away and gigantic mass of land that is his home, Australia. Yet his work does not fall into the easy sentimentalism of a chauvinistic revisitation of the vernacular. Rather, a considered, serious look would trace his buildings’ lineage to modernism, to modern architecture, and particularly to its Scandinavian roots planted by Asplund and Lewerentz, and nurtured by Alvar Aalto.”

Jorge Silvetti, Pritzker Juror

An architecture of integrity – Haig Beck and Jackie Cooper

Marie Short house, Kempsey, NSW, 1974-5, extended 1980. Image: Anthony Browell.

Murcutt guest studio, Kempsey, NSW, 1992. Image: Anthony Browell.

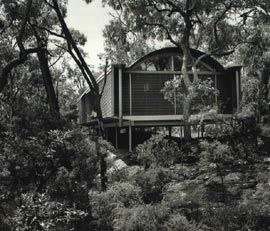

Ball-Eastaway house and studio, Glenorie, NSW, 1980-83. Assistants Graham Jahn and Rad Milatich; Alex Tzannes, site visits. Image: Anthony Browell.

Singular

“A bottle of brandy came out and friends drifted in. It was about two in the morning. Most of the arrivals were students. Vincenzo was an architecture student living in the Vucciria. He talked eagerly about Glenn Murcutt. He said he would have given anything to work with Murcutt in Australia. I told him quite gently Murcutt had no assistants, that he always worked alone.”

Somehow it’s quite natural to find Murcutt’s name cropping up in Peter Robb’s richly conspiratorial book about Sicilian politics and history. Glenn Murcutt is known far beyond Australia. He has become an international cultural figure, feted from Scandinavia to North America. In 1992 he was awarded the elite Aalto Medal, becoming one of only eight architects in the world to hold the rare honour. And now the Pritzker Prize, his induction into architecture’s version of the Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Fame. Imagine any of the other recipients of this high-profile international prize attaining such recognition by running a solo practice for thirty-five years.

But for most of his career, Murcutt has worked alone, with no staff. He is notorious for pulling the phone out of the wall when he’s busy, and a few years ago his engineers gave him a fax machine to ensure they could communicate with him during these periods of withdrawal. Murcutt certainly isn’t a loner and he welcomes collaboration; he’s worked with Troppo, his wife Wendy Lewin, Reg Lark, and also his son, Nicholas Murcutt. But his preferred singular mode of practice allows him greatest control over what he does, and clients wait patiently until he can attend to them.

Free

“Moving inland into the hills of Sicily, where the villas are bigger, more costly and solid, the new houses look more and more like dreadful fortified bunkers. As they are. There is no grimmer or more palpable expression of the social ethos in Sicily…[The houses] are the ultimate expression of fear and mistrust of your neighbours. Thinking this now…I saw the amazing appeal the Australian houses of Glenn Murcutt must have had for the student Vincenzo, sitting so airily and lightly and modestly on the earth, minimal, essential and open to the world around them. From Sicily such houses seem models or dreams of another world, another way of living, and seeing this, I realized as I hadn’t earlier the politics of Vincenzo’s enthusiasm.”

From Sicily, an island doomed by a diabolical system of social and political bondage, an observer would naturally look with longing towards the open, free, easy way of life embodied in Murcutt’s architecture. His buildings are light and airy and minimal, and they speak of a cultural and social ethos that is enviably casual and encourages direct engagement with the environment: safe, not fortified behind thick walls: “another way of living” indeed. Nevertheless, it is curious just how few Australians choose to live this way, freely and openly embracing their surroundings; instead the majority mediate the outside world via air-conditioning and swaddle their houses in stylistic iconography. Murcutt, it should be remembered, has fought some deadly battles against reactionary local authorities locked into “contextual” planning paradigms based on historicist pastiche.

Universal

While his architecture is far from popular among Australia’s mainstream, Murcutt has defined contemporary Australian architecture to the rest of the world, and in significant ways to Australia too. The universal appeal of his work lies in its rigour, simplicity and clear response to place. He does not draw on the vernacular but operates from rationalist premises. His buildings have an existential quality: ideologically based, experientially nuanced, meticulously thought through.

Murcutt’s appeal to architects is unequivocal. Good designers everywhere recognise the absolute integrity of his aesthetic: it is pure rationalism: functional, rigorously responsive to climate, no redundancy in any of the members, everything honed down to its functional and aesthetic essential. Architects see that and wish that their own work might be less compromised. And when they study his drawings, they see the building drawn into life: every bolt, every screw-head aligned, the grain to the timber members correct, the sanitary fittings exactly as they will be installed. Murcutt allows nothing to cloud the clarity of his vision of the building. His architecture is not driven by formal invention. It’s just rational. This clarity enables architects, wherever they are in the world, to imagine themselves practising with the same rigour and integrity, responding to their own place, materials, practices, and philosophical imperatives. Glenn Murcutt is an architectural Everyman, which is why he is so universally admired.

Glenn Murcutt’s a top bloke (but a crazy driver) – Phil Harris and Adrian Welke

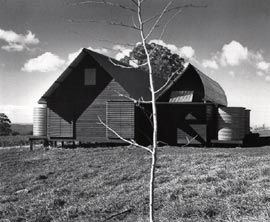

Nicholas farm house, Mt Irvine, NSW, 1977-80. Image: Max Dupain.

Magney house, Binji Binji, South Coast, NSW, 1982-84. Image: Anthony Browell.

Someone should slow down this fella’s mind – and his car. (Or maybe we’re just not used to Sydney traffic.) We all know, “Draw and Drive, you’re a Bloody Idiot!”. With our subject, “Debate and Drive” can be worse; and don’t let the debate get on to councils.

Glenn Murcutt was a hero of ours at university. Remember the 1970s Nation Review? There must have been a six-page spread on the Mt Irvine and Jamberoo houses and Glenn’s approach to a new-but-old Australian architecture, complete with bits of working drawings. At Troppo Year 1, in our shopfront office, we had made a mobile of it (and hung it alongside the Troppo t-shirt and showbag, then popular with Melbourne schoolgirls on tour to the Top End). It was at this time, late in the dry season of ‘82, that the fellow himself, replete in outback khakis and with sweaty brow, popped his head in the door. We still don’t know if he was looking for a t-shirt or wanting to hit us for copyright on the mobile. Either way, he was clearly thirsty. Once ensconced with a cold one in the garden of the Hotel Darwin, we got down to things regionally architectural. And after that modicum of GM pep, for us rather friendless, low feeearners in the blockwork-and-concrete, post-Tracy-trauma architectural world of Darwin, things never really looked back.

To practice architecture is a full commitment, dealing with people’s dreams and bank balances. To practice on the edge, pushing council guidelines and new approaches to construction is an even fuller one – if you’re to pull it off. And to do this as a sole practitioner is inconceivable to those who consider sleep a basic. Add to this, the demands of learning institutions and the public at home and abroad and its not surprising to know that Glenn doesn’t get to the footy often.We witnessed Glenn’s return to his Mosman office after receiving the Alvar Aalto: the endless loop of fax paper draped over the kitchen chair was enough to have one running back to the airport. But, despite the despair, a hasty retreat was not for our hero: more battles, more magic awaited his hand.

And more young architects and students awaited his generosity of time. His record of patient collaboration with younger practitioners speaks for itself. But, to work with Glenn is to work with a friend, and unavoidably a family friend: he can never remain a mere work associate of the bloke/sheila with the briefcase. He also likes to gather old friends, to reminisce of the days of student struggle, and to share evolving journeys into the architectural future. He doesn’t forget people, be they his oldest teacher, or your kid. Even to less-old friends (and that’s us), no details are secret (yes, neither architectural nor personal); advice is at the end of a phone or fax (but definitely not an e-mail!). And it’s free and wise.We have ferociously adopted his dictum of recognising an insideoutside continuum: design in section, and design from the inside out… Think of how passage is made through the space by you and by every other type of user, by light, by air; in different circumstances; at different times of the year, the day, the night. And find dynamic, kinetic ways to respond broadly and sensitively.

He talks of builders, tradesmen and suppliers as his allies and co-design-developers: more brains, more experience to bring to a project: more wisdom to learn from.

To be out bush with Glenn is a delight. Not only is he always seeking to know more about the way in which a landscape works in an ecological way, but he seems to just love being there, among the colours, the light, and the forever-changing, interplaying natural elements. Like a pig in shit, really.

Seeking to understand Aboriginal ways of relating to these settings also recurs as an around-the-campfire-or-table theme.We had the pleasure to travel with him to “visit country” with Kakadu’s Big Bill Neidje at Cannon Hill. Under the ledge of an escarpment outlier, the little whitefella with his floppy hat and bifocals and the grand man of that country, Bill, were oblivious to the rest of us as they slipped easily into discussing the state of the “World”. The surrounding rock art – another Murcutt passion – was just a lead-in, but seemed momentarily more alive. This was a meeting of earthly reassurance, of kindred, strong spirits: for those brief hours, the planet seemed to be in safe hands. And maybe it’s this sense of a bigger order of things, and the humble place that things man-made play in it, that enable even his smallest projects to reach brazenly out to the Great Outdoors though a very big “frame”. A whole operable louvred wall: why not? A roof that lifts up to the tree-tops: why not? Small in square metres maybe, but big in confronting ambition.

We guess it’s an understatement to say that Glenn’s not afraid to preach. If something is simply not logical, just or appropriate, he’s not afraid to say so. A quick study of his RAIA awards jury work in the NT reveals his redefining of categories to become Territoryrelevant; his on-the-night awarding of the outdoor awards venue (not much more than a banyan tree); and the co-awarding of a client as project designer. (Bloody fun nights those!) Maybe this “preaching” is more correctly “enthusiastic hypothesising”. This a sound, scientific approach to developing knowledge: set out your thinking, your ideas, your perception of truths, and then amend them according to resultant experience and that of others. Yes, of course to hypothesise is to risk being wrong and attracting the knockers. But, in any case, just watch audiences respond to his thinking, his speaking, his passion: to give wholeheartedly of yourself, to bother to seek to energise others, to move thinking on, is a special community-minded attribute, and… bloody brave. We are with you, Glenn: go on folks, get out on a limb, too: the air feels pretty good out there.

Murcutt and the architecture of discovery – Elizabeth Farrelly and Glenn Murcutt

Minerals and Mining Museum, Broken Hill, NSW, 1987-89. Assistant Reg Lewin. Image: Glenn Murcutt.

Littlemore House, Woollahra, Sydney, 1983-6. Assistant Wendy Lewin. Image: Max Dupain.

Magney House, Paddington, Sydney, 1986-90. Site assistant, James Grose; landscape architects, Andrew McNally and Sue Barnsley. Image: Anthony Browell.

Marika-Alderton House, Yirrakala, East Arnhem Land, 1991-94. Image: Glenn Murcutt.

Simpson-Lee House, Mount Wilson, NSW, 1989-1994. Image: Anthony Browell.

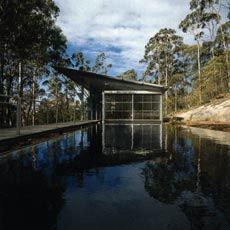

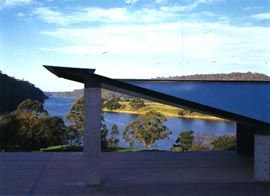

Arthur & Yvonne Boyd Education Cntre, Riversdale, NSW. In collaboration with Wendy Lewin and Reg Lark, 1996-99. Image: Anthony Browell.

Fletcher-Page House, Kangaroo Valley, 1997-2000. Image: Anthony Browell.

E. M. Farrelly So, this is pretty exciting, isn’t it? Architecture’s Nobel?

Glenn Murcutt It is exciting. Not to recognise that would be to deny reality. To spend a long part of your career knitting one purl, one plain, operating mainly below the radar level, and then to receive one of the world’s great prizes is amazing. It’s almost small is beautiful. And out of the blue, too. Quite a shock.

EMF It’s not just the Pritzker, is it? You’ve received quite a few awards recently?

GM Well, I got the Thomas Jefferson medal in the US, last year. And the year before that the Richard Neutra award, for practice and teaching, and the Green Pin, an ecological award from Denmark. Last week I received another international reward from Denmark, which is called “Making a Difference”. And the Kenneth F. Browne award for Asia/Pacific architecture, for the Boyd Centre.

EMF Plus, there are various chairs and things?

GM Yes, I have a visiting professorial chair at Yale. And one at the University of Washington, St Louis, which runs ten days at a time. There is a visiting distinguished architect position at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, just for a short time, a studio at Cornell later this year, a masterclass at the University of Technology, Lae, every three years or so, and next year the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. I’m all over the place, it’s a whole new world for me, it’s just exploded.

EMF So this must feel like a crowning achievement – retrospectively, though, which project are you most proud of?

GM I don’t suffer the problem of pride too much. I’m always worried about the next step. Of course, every client wants to think their’s is my best work. But one of the most important projects was working with Wendy and Reg on the Boyd Centre. It is also a public building. That is important. In every building, though, I’ve tried to research something. Whether it’s wind, light, sun, ventilation, prospect, refuge, path, security. Every building has something that helps build vocabulary. But there are clearly certain buildings whose clients have enabled me to go further than otherwise. For example, the Simpson-Lee house at Mt Wilson is a very important building for me, and it’s important for those who have visited. Although it wasn’t good enough for the National Jury to visit.

EMF They didn’t even bother to see it?

GM No, they didn’t bother to see it. It won the Wilkinson Award, but they didn’t even bother to see it. But that’s alright.

EMF Is there anything that stands out as the most difficult?

GM Most difficulties are really when one hasn’t fully understood the aspirations – or lack of aspiration – of a client. Often lack of aspiration is what kills a job. If the client doesn’t have the energy and perception to drive the best from the work, then it won’t come.

EMF Have you ever got to the point of sacking a client?

GM Yes. But not often. I try to do it before I even start.

EMF I imagine it helps shorten the waiting list. How long is it now?

GM Put it this way, Wendy and I have enough work on, together and independently, to keep us going for at least five years.

EMF All in Australia?

GM Yes.

EMF: Do you have aspirations to work elsewhere?

GM No, I don’t need to. I turn those invitations down. Working in America would be hell. They sue at the drop of a hat. I’ve been invited to work in Finland, which might be nice, but then you have to have an associate and if they are any good, they won’t want to do somebody else’s documentation and site inspections. So it’s out of the question for me. I know that’s fairly old hat. With globalisation now nobody could care less where the work is. But the real question is what are you offering. In architectural terms, what are most of these architects offering other societies? There’s a level of arrogance associated with it, in my view. I’m not saying we can’t build in other places, of course we can. But you do have to consider who is being knocked aside in that country, what we know about that country that they don’t know, and why we do it, other than making money? Why is everybody into China now? Not to help the Chinese. It’s more take than give, and I’m not interested in that. That’s not my way at all.

EMF But you’re clearly comfortable teaching overseas?

GM Teaching is different. One is talking principles, and principles are about questions.

The answers vary, but the questions are the same. Culturally, climatically things shift.

What is the significance of entry, from Mexico to Spain to Scandinavia? What does it mean to arrive? In Scandinavia entry is largely about keeping the cold out; while here in Australia we think much more about taking our clothes off. We are always preparing for the summer, the Finns are always preparing for the cold, thinking about putting clothes on. While they think about low light, we think about the high light intensity – very different psyches. But there are huge overlaps between these essences. Probably my closest friends are Finns.

EMF Why is that?

GM There is a spiritual similarity. You can’t talk to a Finnish architect for more than five minutes without mentioning place and nature. In Finland there are five million people and thousands of lakes, so everyone has a potential escape. And because the winter is cold, going to nature when one can becomes extremely important, the quality of light is very important.

But teaching is about principles, about placement, hydrology, geology, geomorphology, the place history, climatic conditions, meteorological conditions; we talk about water table, rainfall, humidity, wind patterns; we talk about animal tracks, insect movements.

Or, in an urban context, wind conditions, pollution levels, sunlight and humidity levels.

All these are questions of principle, so these things you can teach. It is a common language. For example, the Finns love big windows and they love to use screens. I realised that the screens are to break down the level of light, light reflected from winter snow – just as we use screens a lot now to break down the summer light. Or, for example, Aalto’s s-chairs I use a lot, with the strapping. Why use them? A strap allows the air to flow around your body. It’s very comfortable. The Finns do it because in winter their houses are heated, giving warm air – same thing reversed. So I am starting to realise that opposite solutions are not dissimilar, and it’s a very interesting idea.

I was invited to do the Arizona Sonora Desert Museum near Tucson. I said that I actually do not understand the subtleties of the US society, but I set it as a program at Tucson, where 50 percent of the people speak Spanish, and there were students from Europe, Mexico, South America and North America, and elsewhere.

EMF: Were the proposals noticeably different?

GM: Yes, and different from anything I would have done. I could have built a museum, sure. But I wouldn’t have understood the whole essence. They put such emphasis on fire, for example, and death, and a whole lot of quasi-religious things that I wouldn’t have understood at all, but were significant in generating desert culture.

Utzon is able to fuse elements from other cultures in a way that makes them his own.

Take the Elsinore and Fredriksborg housing, for example. You have Chinese principles, Roman piles, Danish bricks, the idea of privacy and public realm and Utzon puts it together in a way that totally belongs to his place.

EMF But Utzon built here, of course, in Sydney.

GM I am not denying the ability to transfer ideas, but I am simply saying that there are few brilliant people in the world and I’m not one of those. Utzon is. To me, he’s just incredible. I have such admiration for the guy. I think this country did an appalling thing to him. I still feel embarrassed. I met an architect who lives in his Frederiksborg scheme and he said he just thanks God for Utzon every day.

EMF So, do you ever have any regrets about being an architect? Do you wish you’d done something else?

GM Every time the phone rings and takes me away from what I want to do.

Architecture is a wonderful, fantastic activity. The biggest difficulty is that societies are so conservative. Councils especially. I find councils very difficult. I know they have to respond to community needs. But if the community is so conservative, it makes it impossible for architects to move beyond conservatism, impossible to produce something relevant to today, and tomorrow.

EMF You have had a battle with Mosman Council over your own house recently, haven’t you?

GM: Here was a building entirely within the LEP profile, which if anything increased the sunlight to everybody; entirely within privacy issues, entirely within materiality; modern yes, with changes at the back, but the front was basically unaltered. We finally got an approval, requiring us to discharge stormwater onto the street, although we all know, internationally, we should keep water on site the better, rather than taking every piece of dog shit to the harbour. And this drainage requires me to drill through the roots of native trees, while placing a $15,000 bond on those same trees, because they hide the roof lights from the street. The council guy said, “we’re going to be changing our stormwater rules and we’d like you to make recommendations, but these are the rules now and you have to comply.” Is that ludicrous or not? It’s madness. I’m amazed people put up with it.

EMF Depressing isn’t it?

GM For any young architect working in this country who hasn’t got the spirit to fight it, you put your tail between your legs, go away and accept mediocrity, total mediocrity. Yet this country has some of the brightest and most talented people in the world. Utzon showed us how. The Opera House is as good today as thirty years ago, but everyone was outraged at the time – we should build more hospitals and so on. All the conservative voices came out – yet it brings in $2 billion a year to this country. This is a nation terrified of change.

I think we now have the worst federal government ever. I am disgusted. I can’t tell you how angry I feel about this. What embarrassment it causes me internationally! I was challenged and challenged in Denmark, I’m challenged in the US, I’m challenged in Italy, challenged in every country in the world. And I feel so disgusted by what are clearly lies and manipulations of the truth. I nearly go berserk. They’ve cut education, they’ve cut culture, they’ve cut everything that really matters in life. It has been an intellectually defunct government. Barren to the core.

EMF Why is it like that, do you think?

GM I think we are still an insecure race of people, far flung. Insecurity is the basis of our conservatism. When we become secure in the knowledge that we can do very good things, then change can happen. Wonderful change.

EMF Do you see it changing?

GM A few of us have tried. I haven’t had a lot of court cases for nothing. I think it requires a lot of people – architects – who will drive change. But some things are getting worse. For example, this integrated consent system is a really significant issue. It requires so much information up front that we essentially eliminate the design development phase.

EMF Is practice harder now than it was?

GM Yes. It’s much harder for me now than 25 years ago. My buildings fail the bureaucrats’ environmental tests. They perform wonderfully in summer and winter but have to prove it repeatedly, wasting time and money. And I’m still having problems with councils over aesthetics. Ken Done had to paint his house of natural tones – so he argued that yellow was a natural tone and so was blue. But he really wanted to paint it white. What colour is it today? White. So this is stupid. You either get angry, mad or depressed. I get shattered each time initially, then angry. I haven’t let them beat me.

But any architect who is sensitive or doesn’t like fighting – they put their tails between their legs and go away depressed. And I don’t blame them. I think scale, typology, morphology, materiality – these things should probably be within council control. But aesthetics should be off their agenda.

We should accept change in our built environment. I think there is a place for an environment that is dynamic and evolving; what doesn’t evolve, dies. It’s extremely important when you look at the work of Sverre Fehn, for example, or Carlo Scarpa. Both combine the modern with the old so they are clearly distinct, but the relationship is powerful and joyous, reinforcing both.

EMF What about the heritage/conservation question?

GM This is another issue. The Burra Charter should prevent replication, which debases the original. I learnt enormously on the Aga Khan jury. We were advised by one of the foremost – if fundamentalist – thinkers in archeology, for whom restoration is a dirty word; conservation is the only thing. Conservation reveals the original work in its entirety, allowing it to breathe and clearly distinguishing new from old. If there is any confusion, it’s out.

Now, this was fundamental for me as juror. There was a fantastic project in the awards which was overruled because our specialist picked where some panels were repainted to match the originals. This guy is in charge of the sphinx and pyramids. When the sphinx was crumbling they finally repaired it in plaster, which needs replacing every five years, in order to maintain the point of decay, and clarify the difference. Conservation is about holding it where it is. This gives the principle of age, of time.

EMF: And do you agree with that principle?

GM: I think it’s very sound. For example, in Sverre Fehn’s Museum at Hamar it is very clear what is old. [The Hamar Bispegard Museum, Norway, Sverre Fehn, 1970, built on the site of a fourteenth century bishop’s manor.] At the entrance, all the stones are falling down and Fehn put this sheet of glass right across, a big square of glass, which ends at the doors. It’s very clear, which makes for a much richer solution. But in this country it’s not allowed. There is this conservatism, this lack of understanding, this ignorance. At root, it’s ignorance.

EMF What is the solution do you think?

GM: Education. If design was taught from a very early stage – not design as aesthetics, but design about the shaping of a rock in a river, the structure of plants. If we look at that, then look at bridges and catenaries, and teach the principles. If we looked at aesthetics as principles, not just what you like, but the core of truth behind natural structures, kids could start to assess and analyse.

EMF How important is drawing? What will happen when architects can draw only on screen?

GM The mouse only makes repetition easier. When we lose the ability to draw, we lose a part of our ability to think. As my engineer pointed out to me, there is no way I could design on computer because to take a line to go from A to B, you first have to define point B: when you draw, your hand and mind takes it there. It’s a totally different process. We are smart enough as a race to develop instruments to make our work easier, but not smart enough to fit our instruments to the way we should develop. We allow instruments to dictate the way we think.

Before the theodolite, we built according to topography, water flow and gradients. So the historic streets of Dubrovnik or Italian hill towns were linked by staircases and it all worked in a very human, carved way. Then theodolites came along and we ended up with grid patterns. We let the instrument do our thinking for us. The computer is no different. It promotes certain ways of thinking and practice.

EMF Speaking of straight lines, you once said you’d been trying to escape Mies all your life. But the Miesian quality of your plans is still evident. Very orthogonal, very disciplined. Are you ever tempted by curves or fanciful geometry?

GM Sure. In the Boyd Centre we changed the geometry, very distinctive, different geometry. The hotel project Wendy and I are working on in Victoria currently has shifts in geometry all over the place. Even the little entry deck to the flat at Kempsey had a shift in geometry. They do appear. But I won’t do things for the sake it. I think of the difference between Aalto’s curves and those of almost every other architect is that Aalto knew when not to use two curves consecutively. He knew that a curve was always followed by a straight line before another curve, as opposed to curve upon curve upon curve, which can be very syrupy. I could never allow myself to do that. I don’t think it works spatially.

But can I say that Mies, almost unconsciously, is still my conscience. Every project begins in an unbelievably confused and complex way; and it’s by working and working at it that I try to find that essence – that simplicity which is the other face of complexity, as opposed to the simplistic which just omits complexity.

EMF Do you have a standard design process then?

GM Sure. I just keep at it. Trying to resolve plan and detail. The details are part of the whole thinking process right from the outset. My drawings have details all over them at the design stage.

EMF And elevations? Do you have them on your mind throughout?

GM I hardly ever go to elevations until near the end. Although once I start on them, I do go back over, manipulate a few things. But I do have them in mind. I’m always trying to understand how the water will move across the roof, asking whether I should put in the diagonal gutter, or a monopitch roof.

EMF What do you do first? Do you have a way of getting into a project?

GM Yes, a very clear way. Avoiding it until I have to. But I’ve known for a long time what I want to do and I’m thinking about it a lot. When clients come to me I see them once or twice to see if I’m the right architect, and then there’s the wait period. It allows the project to sit in my mind, and them to write their brief.

EMF Is that hard?

GM: Many clients find it difficult. Some clients are very lucid, but even so it makes an enormous difference to their thinking, and they often actually change through the brief writing, as well as the wait period. I’ve had clients start off with spa baths and technology everywhere, with space for this and that, but as costs rise they have to be tighter, and the result is a much better building.

The trouble is that these days both Wendy’s and my buildings lack fat. So to cut the fat out is very hard. To make spaces smaller or finishes more economical is very hard. It’s hard to go past bagged brickwork and gyprock. I like the lack of fat as an idea. I like a lithe building. I love the quality of emptiness.

EMF Why?

GM The silence. It can have a serenity. In Barragan’s words; “any work of architecture that is designed without serenity in mind is, in my view, a mistake – and when serenity possesses joy it is ultimate”.

EMF What is the quality, do you think, that endows a space with “serenity” rather than just emptiness?

GM In part it’s avoiding confusion and clutter. I hate clutter, although I’m the world’s most cluttering person. I love light and space and connectedness with landscape, the outside, the sky, the plants. I find those connections really important. Here we are in your typical suburban house now, this is a middle suburban sort of house, there is basically nothing wrong with it. [Murcutt and Lewin are living in a rented house while their own house is renovated.] I can understand why people say, what’s wrong with them, they’re marvellous, we can go out the laundry door, to the backyard and have a barbie, I can understand that, but there is more to life than all of that. I’d give anything to be able to smash holes in the back here, open up parts of it, have doors that breathe to the outside, allow the outside to come in and breathe in and out, one has to have lungs in the house, space, ability of the outside to move in and inside to move out, They are very important issues for me.

EMF You said once that you thought the city unredeemed. And of course your best-known projects are rural or semi-rural. Do you ever yearn to work on complex city projects? I still wonder what might have happened if you’d completed work on the Customs House, for example.

GM In the CBD the answer is yes, but can they wait three years, five years? But the whole problem for me is the frustration of bureaucracy, and the question of turnover.

Each project is a small experiment. I’ve built at least 500 buildings so far: how could I get that level of experimental feedback with a single building taking five years?

I’ve been contacted by architects internationally about things I’ve developed, like shading devices, and whether I’d mind their using it. Of course I don’t – I send them working drawings. There are no patents in my mind.

But look, this is the old chestnut. People always say, “anyone can do pretty houses on hillsides. He’s never had to tackle the really difficult things.”

EMF And do you have a stock response?

GM No, I just let them run with that. They are really stating their own insecurity about their own compromises. Behind all these barbed statements lies a level of anxiety. And when people say all I’ve done is design pretty houses on hillsides, anyone can do that – well let me see all these pretty houses by all these people on the hillsides, and I’ll tell you if they’re pretty or not. That’s about it, a few pretty colours. They can make those statements forever. That isn’t my issue.

And when people say “don’t you want to do a city building, or a major building in the city?” I actually don’t know where that question is coming from, other than ego. It can only be ego that drives that sort of question. I have a great interest in doing architecture but often one big building can destroy the possibility of many other buildings. So the answer is no. They say, “why wouldn’t you want to work internationally?” I say, “I don’t need to do that.” If you want to work internationally, then you probably have a need to do that. That need is probably something about ego. I think ego gets in the way of design. I don’t have a need for all those things.

I still hold to that old statement of my father, that in life most of us will do ordinary things, and the important thing is to do those ordinary things extraordinarily well. And be able to go to the beach where nobody knows who you are. Therefore ego is not a big thing. Ego has many sides to it. One side of ego is driving force, that is very powerful for me, a driving force. But the egotistical side, the ego of self, is far less important. For me the question is, is it worthwhile? Apart from financial benefit, is it worthwhile for my spirit? Why do it? Why? We’ve got one life. One needs to give the best of oneself. The Boyd Centre was a much better project for us than the Customs House. Big urban projects, like undergrounding railways in Barcelona, would be great. But I’m not good at compromise. On the other hand I don’t feel I’m an arrogant person. I just feel my time is being wasted.

EMF You must find domestic projects involve compromise, though?

GM Of course we compromise on houses, but I wouldn’t want to waste my time on a bigger thing where all my time is being compromised. And I think that, as architects, each of us has a responsibility to give the best of ourselves. If we design things we know are a terrible compromise, it’s a very painful experience.

My father gave me some very good advice when I started off. He said, “son, now that you’re in your practice, remember you must start off the way you would like to finish.

And secondly, every compromise you know you are making, that represents your next client.” It’s very easy to be bad in architecture. It’s a very hard occupation in which to do good work and any good work is to be admired.

EMF People often twin you with Richard Leplastrier, as Sydney exponents of beautiful and thoughtful domestic work. How do you view that parallel?

GM I agree with it. We’ve done things differently in life, but we have in common a love of place and architecture. I feel enormously warm towards Richard, with an immense respect for his abilities.

EMF You didn’t study together though did you?

GM No, we taught at Sydney University together. We coincided in teaching and we just found that, whilst our work is very different, there is a similar belief. As Coderch [Josep Antoni Coderch] said to me in 1973 you must put into your work firstly effort, secondly, love, and – very Spanish – finally, suffering. I share with Rick that dedication, care, responsibility towards the work, the love of it, most of the time, and the difficulty of it, the painful side of suffering.

Coderch taught me another thing. He said, “for every new project I am very nervous.” I was 37 at the time and that was the first time I ever heard any architect admit to being nervous in starting a project. I’d never told anybody I was nervous, but I always was. Here was the father of Spanish modernism, still nervous at the age of 70! Now I’m only four years off that myself and realise what an incredible truth it was. It released me.

That, together with the House of Light by Pierre Chareau, released me. I realised that it was essential to be nervous. It was essential for me to have seen that modern architecture can be open-ended and not dogmatic. Ecology now has become a generally important issue, but it has been with me since almost the first days of practice.

EMF Why is that, do you think?

GM I was raised that way. I was always taught about erosion. My father propagated native plants in 1946 and 47, putting seeds in the oven and pouring boiling water over them, then he’d surreptitiously go back and plant these plants as a means of reafforesting the hillside. He would orient buildings to the winter sun and the breezes, he ventilated and built curtain walls in his buildings. And we helped him. Why did I start this way? I had no alternative; it was the other conscience. So Mies is one conscience and my upbringing is the other conscience.

I got a book in Denmark the other day on Craig Ellwood, with a note from Neil Clark, the author. He’d found a letter I’d sent to Craig in Ellwood’s files, asking to visit him, which I did. There was also my response to that visit. I had asked Ellwood how he dealt with heating and cooling his building. This was 1973. Was there some smart glass in America I didn’t know about? He looked at me as if I was mad, and said, “we have tinted glass and we install air conditioning.” I felt so stupid. This is in Neil’s book. So right from the outset I was clearly interested in response to place. It’s nothing new.

EMF What would you say is the relationship between ethics and architecture?

GM It’s a subject not taught at university – the ethics of decision making, projects we should and shouldn’t do. I believe it’s very important we make a decision about the projects we do and don’t take on. I wouldn’t design huts for the detention of people in Australia, for example. To me that is unethical. I wouldn’t have a bar of that.

EMF Even if you could make them better?

GM Even if I could make them better. Because once we accept the detention, that is a given. We shouldn’t accept it. We should say, how can we clear people very quickly?

There is no need to hold these people for this long.

EMF: So, do you feel you need to approve of your clients?

GM If you went fully into it, you might, if you were totally fundamentalist about the ethics, you would investigate the background to the client’s wealth.

EMF But you may not end up with many clients?

GM That is true. I know Ted Cullinan in England was invited to work for a big computer company that had been involved in warfare systems, and he refused the project. I know the client, too, and he confirmed it. I haven’t investigated my clients’ background to that extent. I did come unstuck with one client, whom I should never have taken on because he is, frankly, a bully.

EMF Isn’t it an irony inherent in small, one-off domestic projects that you work generally for the rich?

GM That’s not true. Everyone says this. I have done Aboriginal housing for no fees. I did a garden-shed house for a school teacher with no money, also for no fee. And I’ve often done things twice without charging fees as well.

EMF But architecture does cost money, on the whole?

GM: No, architecture doesn’t make money. It’s about the only occupation that would do a thing twice without charging twice.

EMF If you had to try and encapsulate the point of architecture, the purpose of a lifetime doing it, what would you say ?

GM The only purpose is to live so that you end each day saying, “Well I’ve achieved something today.” But architecture holds a remarkable series of issues. We deal with people, with building, with materials, with clients, with art, we deal with structure, life style, food preparation, bathing, sleeping, privacy, prospect, sound, acoustics, music, finishes, colours, access, vehicular movements, street patterns, landscape. What aren’t we dealing with? Money, too – is there another such occupation? At its fullest level architecture is an extraordinary occupation.

It can be extraordinarily rewarding emotionally and extraordinarily unrewarding financially, which is fine, as long as we survive. Of all those people who make all the money in the world there are very few that I can say I really respect what they do with it. It’s not about buying racehorses. Not for me. It’s outside of all that.

EMF What is it about then?

GM It’s a marvellous expression of the process of discovery. That is what it is. It’s an incredible process on the path to discovery. It’s like a scientist on one level, who doesn’t know the answer but knows the path to it, the path of discovery.

I am very suspicious of creativity, very suspicious of it. I think that any work of architecture clearly had the potential to exist. Our path is that of discovery. Our role is to discover. We don’t create, we discover. Creation embodies an arrogance, an elitism, something you are gifted with. I don’t see all that.

It used to be thought that if you could draw beautifully you were creative, if you were artistic you were creative. No, I’m saying that is the path to the discovery, the work finally is the result of that discovery. That is what I’m in it for, the joy of the path, the discovery.

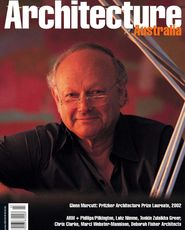

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 May 2002

Words:

Haig Beck,

Jackie Cooper,

Phil Harris,

Adrian Welke,

Elizabeth Farrelly

Issue

Architecture Australia, May 2002