The pedestrian experience of the central arch structure of the Goodwill Bridge. Image: Stefan Jannides

The South Bank approach, along the “rampart”. Image: Stefan Jannides

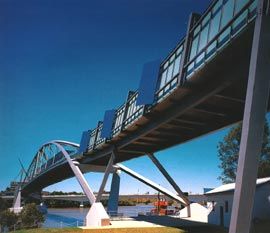

View from under the long “rampart” approach, spanning over the Maritime Museum yard, towards the central arch. Image: Stefan Jannides.

Looking over the bridge towards the Maritime Museum and South Bank. Image: David Sandison.

Pedestrian level view of the central suspension structure supporting the arch and the cantilevered deck. Image: Cox Rayner.

Brisbane’s recasting of its identity, in the 1990s, as “River City” elicited romantic visions of a river and its banks brimming with activity. These visions were, however, challenged by the scale of the river itself, which often seemed simply too big to allow this kind of active intensity. The Goodwill Bridge, the most recent addition this riverscape, successfully addresses the inherent problem of scale through the implementation of a set of ideas linked to its use. It works simultaneously to enliven a potentially over-extended pedestrian experience, to mediate the scale of its structural elements with human scale, and to impart an identity and presence that allows the bridge to register beside adjacent large-scale elements such as the Riverside Expressway and Captain Cook Bridge. Its procurement involved reconciling the competing interests of a range of user groups and interested parties and its achievement has been recognised in the RAIA State Awards program. Yet, every stage of its inception was scrutinised with suspicion and countered by negative propaganda from many quarters.

Successive Brisbane Plans have proposed bridges, both pedestrian and vehicular, which have not eventuated. The process leading to the realisation of the Goodwill Bridge began with a proposal for a pedestrian and cycle bridge specifically connecting Brisbane City to South Bank Parklands in the 1995 Brisbane City Centre Strategy Plan by Cox Rayner. With the inclusion of the bridge as an element in the Denton Corker Marshall South Bank Master Plan, its prospects improved. The development of the idea of the bridge as part of that planning process, and especially the contribution made to it by Robert Riddel, lifted general expectations and ensured a certain quality of outcome. A limited design competition, held in 1999, was won by Cox Rayner.

While the bridge location had been determined generally by the master plan, the fine-tuning of its specific siting was a result of consultations between Cox Rayner and government agencies and interested parties, including South Bank Corporation, the Queensland Maritime Museum, Queensland University of Technology (QUT) and a mostly hostile residents group. Early intentions, explored in the master plan process and |revisited by Cox Rayner, to position the bridge as an extension of Alice Street were rejected because of an uncomfortable fit with South Bank’s lagoon directly opposite. Instead the bridge spans 450 metres from Gardens Point (where it is forced to negotiate Captain Cook Bridge) to the southern end of the South Bank Parklands adjacent the Maritime Museum. Strategically, it inserts itself on the gardens side at a point where a break in the mangroves coincides with the clearance under the Captain Cook Bridge. Opposite, it sweeps down across the museum site to meet a rise in the landform behind the river edge, thereby minimising the length of bridge deck required to reach ground.

Together with Victoria Bridge to the north, the Goodwill Bridge encloses South Bank Parklands in a circuit, with the bridgeheads tailored to tie the bridge back to this circuit. However, the level of attention lavished on this new urban set piece, and in particular the QUT bridgehead, confirms the Queensland Maritime Museum’s comparative impoverishment, an imbalance which now needs addressing.

The design of the Goodwill Bridge departs from a “singular” structurally driven solution, and instead adopts a distinctly architectural approach. This involved teasing out and amplifying a series of experiences, and linking them to ideas of “pier”, “arch”, and “rampart”. This ideas-driven strategy is matched with a hybrid structural system, which was necessary to resolve the asymmetrical forces set up by the bridge as it snakes its way across the river. Critical tolerances determined some significant bridge elements. The width across the navigational channel, and the clearances required above it, fixed the location of the single pylon and mast – designed to withstand the impact of large vessels and as a landmark flagging the bridge’s presence against the city-freeway landscape. This pylon and its platform provide a distinct pause point in the journey across the river and serve as a hinge, around which the bridge deck pivots. Changes in direction at each of the three bridge sections avert the possibility of a “gun-barrel” experience, varying views and reducing perceptions of distance.

Every opportunity is taken to mediate between the scale of structural elements and the experience of the pedestrian, and to introduce a sense of lightness and fragility. The central span is achieved by a tilted dual arch structure selected for its stiffness. Cables guy this arch back to the pylon, further reducing the scale of structural members required. Rather than dictating the solution, the structure is part of a language for the expression of ideas.

A second scale and set of rhythms is provided by the screens, canopies, hooded balconies and benches that furnish the superstructure. Each element has its own formal expression, extending the strategy of articulation to all levels of the bridge design. On one hand, the manner of integration of this second scale contributes to a level of visual complexity that is criticised as the bridge’s weak point. On the other hand, “pier”, “arch”, “rampart” harness the opportunities presented by program, context and structure to a set of enduring and legible ideas.

Brisbane’s collection of bridges represents a chronology of its growth and perceptions of identity. The Story Bridge is a heroic structure from a period of optimism in the 1930s. In contrast, functional issues informed the design of the Victoria Bridge, much admired for its elegance, and the more recent Captain Cook Bridge. Structural and material efficiency were directed towards achieving clean lines and unimpeded traffic flows. Pedestrian and cycling experiences were not a consideration.

The new bridge offers a far more poetic experience. It supports the new vision that Brisbane has of itself and its future in which the river plays a role in building networks of communication and recreation that extend far beyond its banks into surrounding city fabric. It offers a different rhythm to the Captain Cook Bridge, being light and nimble in comparison. Far from being a mere engineering exercise, in its bid to shape experience in addition to formal expression, the Goodwill Bridge underscores the contribution that architects can make to bridge building.

Credits

- Project

- Goodwill Bridge

- Architect

- Cox Rayner Architects

Brisbane, Qld, Australia

- Consultants

-

Construction

John Holland Group

Project manager RCP Brisbane

Quantity surveyor Rider Hunt

Services design Barry Webb & Associates

Structural design Arup

Superintendent Department of Main Roads

- Site Details

-

Location

Brisbane,

Qld,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Landscape / urban

Type Public / civic

- Client

-

Client name

Department of State Development

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Sep 2002

Words:

Elizabeth Musgrave

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2002