When Guilford Bell designed Grant House (completed in 1986), he was seventy-four years old. The house, in the Melbourne suburb of Officer, is a classic example of a “late work,” a work that sums up in a mellow way the aspirations of a great career. While it has the pared-down simplicity that comes with years of reflection and refinement, and which is common to many “late works,” we must know that it is laden with significant intention. We are in the world of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 10 …

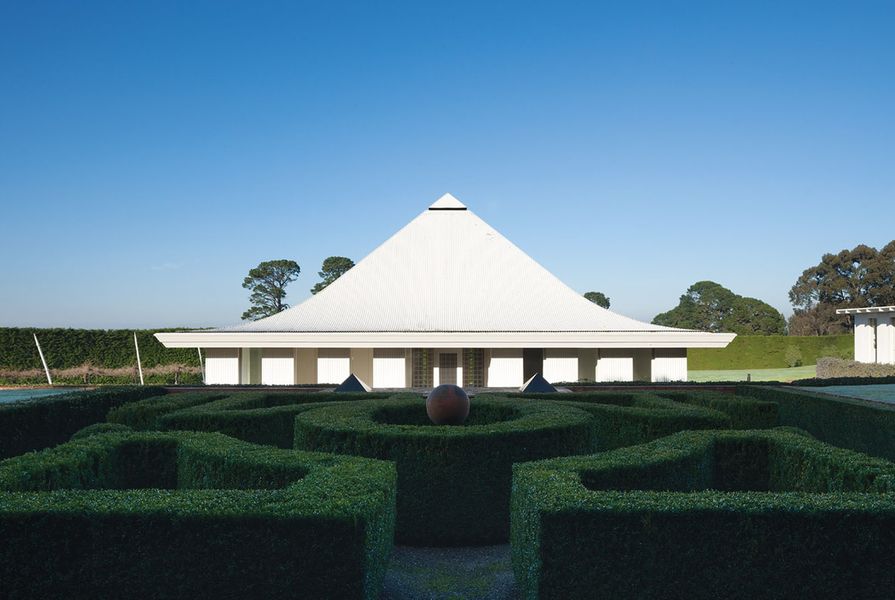

On approaching the site you are presented with a tree-canopied driveway that is framed by hedge banks and faces a row of garages. Above hovers the shimmer of a white pyramid roof, floating ambiguously. Wittingly or not, you arrive on an axis that runs from here through the house, out onto a terrace and down to a lake – an axis that also runs unbroken through more than five hundred years of architectural endeavour from Andrea Palladio (1508–1580), Lord Burlington (1694–1753), Le Corbusier (1887–1965), Louis Kahn (1901–1974), Charles Moore (1925–1993) and Guilford Bell (1912–1992), and continues in the present with, for example, Environment Design Atelier’s Pyramid Roof House in Yokohama, Japan (2011).

In this lineage, the idea has swung from the mainstream of a square plan dissected by cross axes and subdivided into nine spaces, with the central one taking prime place in plan size and in volume, to a deconstructed or syncopated version (Le Corbusier, Kahn, Moore). These diversions have been countered by swings back to a purity that eluded even the mainstream (such as in Bell’s work at Officer). Is this just a mathematical game? What is at stake?

Theorist William Lethaby (1857–1931), whose work would have been known to Bell, if not also to the French and American architects, argued through a series of lectures and essays that architecture is the manifestation on earth of our understanding of the universe. He argued that a highly symmetrical form referring to the four cardinal points with a major space at its centre represents a pre-Galilean concept of universal order, referring back to ancient Roman precedent, and to many of the ideas of the centrality of the hearth to dwelling.

A variety of moods are created by the different gardens.

Image: Dianna Snape

When entering Grant House from its side, in the only deviation from the strict axiality of the plan, we discover that as in all the architectural precedents referred to here – except the vernacular – the underside of the pyramid is hollow, with the ceiling cleaved to the roof slopes. A cross axis divides the square plan of the house. On one side it is separated from a twin-square, sunken parterre garden, as if to register the claim for a Renaissance paternity, while on the other side it leads to a terrace that overlooks grass that extends down to the lake, as if to claim kinship with the eighteenth-century naturalizing landscape architecture of Lancelot “Capability” Brown.

A self-contained unit at the back of the garage.

Image: Dianna Snape

Brick paving runs through the arrival courtyard and the house, and then out to the terraces, claiming the same illusory agricultural pedigree as many of Palladio’s villas in the Veneto. Where the axes cross at the centre of the house, a fireplace rises through the high volume of the internal pyramid of space, a hearth at the centre of the dwelling that harks back to the hearth at the centre of the circular plan of the Temple of Vesta in seventh-century BC Rome.

These may seem charged claims to make for a house, but the “idea of house” that Bell perfected in this late work has a lineage going back to Palladio’s Villa Capra La Rotonda (1591), from which, in the newly international Palladian style, Burlington derived Chiswick House (1792). As Colin Rowe showed in his famous essay The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa (1976), these “nine squares within a square” plans were syncopated slightly by Le Corbusier in the Villa Stein at Garches (1927). He might have elaborated his argument by referring to the way in which Louis Kahn’s design for Trenton Bath House (1955) daringly emptied out five of the nine squares, including the “holy” central one, and roofed the others with their individual, hollowed-out, pyramid roofs.

In his own house in Orinda, California, Charles Moore (Kahn’s pupil and apprentice) used a slightly truncated hollow pyramid roof, and then denied its symmetry by locating two differing scale aedicules within it, quite independent of the axes. What all these architects are playing with is an ancient idea of the house as a representation of the universe, a hearth at its centre. When Bell joins this game in Templestowe, Melbourne in 1972, it is perhaps via the humbler antecedent of a square-plan Queenslander house, symmetrically divided by a front-to-rear corridor and a cross axial breezeway. But he cannot have been innocent of the history above. At his house for the Seccull family (1973) in the Victorian coastal town of Lorne, the pyramid is turned on its diagonal, and the archetypal form is entered playfully on the twisted axis through the carport.

At Officer, we are in the presence of the full gravitas of this “idea of house.” Using Kahnian, thick-wall poche, Bell made all the walls appear to be very substantial. Into the “servant spaces” created by this thickness slide the screens that protect the house from the outside: solid, with flyscreens and glazed. The four corner squares of the plan contain bedrooms, a study, a kitchen and services. Nothing detracts from the ancient claim to a centred, stable space, grounded here in the clay of this ancient continent. This is a very profound argument for calm, for continuity of existence in the face of the turbulent, chaotic processes of the universe. Where might the future for this late, powerful restatement of ancient verities lie? Might there not be a lesson for those of us designing apartment buildings without any stake on existence other than the ephemera of “lifestyle”?

This review of the Grant House is part of the HOUSES Revisited series.

Credits

- Project

- Grant House

- Architect

- Guilford Bell and Graham Fisher Architects

South Yarra, Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Consultants

-

Builder

Owner

- Site Details

-

Location

Officer,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

Site type Suburban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Completion date 1986

Category Residential

Type New houses

Source

Project

Published online: 5 Jul 2013

Words:

Leon van Schaik

Images:

Dianna Snape

Issue

Houses, February 2013