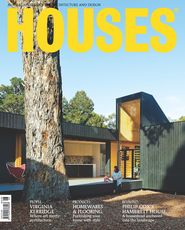

In 1981 Joanne and Bruce Hambrett faced a momentous decision. They had already considered a number of architects for the design of their family home in Dural, Sydney – among them the established practice of Allen Jack and Cottier. But their list was gradually whittled down to a final day and two candidates: Glenn Murcutt and Philip Cox. With trepidation, Joanne called first Murcutt, then Cox. Murcutt, a sole practitioner, was out of the office. Cox’s secretary picked up the call.

Aged in their early forties, both architects could claim to be the leading residential designer of their day. The outsider of the pair, Murcutt, had risen to prominence just five years earlier, when his Laurie Short House, a flat-roofed, Miesian pavilion in the northern Sydney suburb of Terrey Hills, snared the prestigious Wilkinson Award for residential architecture, awarded by the NSW Chapter of the Australian Institute of Architects. He won the award again in 1979 for the Marie Short House, ingeniously cloaking a modernist pavilion in a rustic farmhouse shell. But the slightly younger Cox had a head start on his rival. Cox boasted two state awards for public architecture and ran a thriving practice. His first Wilkinson Award, for the Hawkins Residence, was attained before his thirtieth birthday. Stepping down the hillside on a large bushland block, the brick-and-timber Hawkins Residence exemplifies the late 1960s Sydney School movement.

“Murcutt is the perfect person for Australians: he’s a renegade and looks like a surfer,” says Joanne, “while Cox is perceived as being a bit more silvertailed.” Though it might seem more chance than choice, Joanne and Bruce, who now have three children, commissioned Cox – their decision reinforced by their shared values. Dural wasn’t just the location for the family’s new dwelling, it was “a spiritual home,” a place of connection to history and land. Joanne’s family had lived in the region since the early 1800s, while Bruce hailed from nearby Epping. Tracing his own lineage back to William Cox’s crossing of the Blue Mountains, Cox “has an intrinsic sense of Australian history and the Australian vernacular,” notes Joanne.

From 1968 to 1978, Cox and photographer Wesley Stacey published prolifically on the subject of historic Australian architecture. Perhaps the best known of this series is The Australian Homestead (1972). “I was looking for the genesis of an Australian architecture,” reflects Cox. “The most primitive example was the Australian homestead, with its verandah, a windmill beside it, generating everything in its environment in a passive way.”

The elongated, single-storey plan forms a symmetrical “T”, framing two open courtyards.

Image: Brett Boardman

A traditional homestead re-imagined in concrete, steel and glass, the Hambrett House radically departs from Cox’s earlier Sydney School style. The elongated, single-storey residence forms a symmetrical “T” in plan, framing two open courtyards. While Cox claims an aversion to postmodernism, the house is essentially neo-Georgian, its gable-roofed volumes punctuated by expressed masonry chimneys and trimmed with bullnose verandahs. Adherence to the golden ratio gives internal spaces a classical proportion, each wing culminating in a serene sitting room. It’s a quietly grand house, balancing formality and repose. “People say it’s a big house, but it isn’t,” says Joanne, “it’s actually just one room, meandering across the paddock.”

A two-hectare plot thirty-five kilometres north-west of Sydney, the Hambretts’ site was subdivided from the historic Porter’s dairy farm. “Dural was much more rural then,” recalls Joanne. “We wanted a house that reflected the landscape that it was in.” Consisting of gang-nail timber trusses, slender steel columns and a concrete slab, the house’s structure evokes the unadorned nature of sheds and barns. “The house becomes lighter as it leaves the ground,” comments Cox Architecture director

Philip Graus.

“We wanted to anchor the house in the landscape,” says Joanne. “It was designed to sit lightly in the paddock, but it looked like it could float away. I’d always imagined a country house as up off the ground, and of course this wasn’t: the house sits on a slab.” Curved to minimize structure and avoid the need for eaves or soffits, the bullnose verandah frames and edits views of the surroundings. Unlike a typical homestead, the Hambrett House has glass walls. It is the verandah that encloses the house, with a threshold graduating from concrete pavers to pebble gutter and trimmed lawn beyond. Alternating between roofed portico and vine-covered trellis, the verandah structure veils and shades the rooms.

Though the house was designed to embrace the landscape, that landscape changed dramatically a few years after the house was built. First, a flood inundated the house. Then new neighbours moved to the area, erecting overblown villas where farmhouses had once stood. Landscape architect Peter Lawson was enlisted to install a state-of-the art drainage system. Peter further anchored the house into the landscape through the use of terraces and a series of dry stone retaining walls.

In 1983 the Wilkinson Award jury (for NSW residential architecture) spurned the Hambrett House. Murcutt, however, continued to amass Wilkinsons – in 1982, ’84, ’85 and beyond – extending his repertoire of singular, freestanding pavilions. Thirty years after the Hambrett House was completed, my thoughts return to that unanswered phone call. What would have changed had Murcutt designed the house?

Timber trusses and slender steel columns on a concrete slab, give Hambrett House the unadorned presence of a shed or barn.

Image: Brett Boardman

Like the Hambrett House, Murcutt’s 1980s houses were modernist interpretations of the rural vernacular, with a remarkably similar set of materials, motifs and references. The differences between the two are not formal, but ideological. “Murcutt is single-cell linear, rather than lateral,” explains Cox. “His buildings don’t encompass space, they are emphatic figures. The Hambrett House gives the sense of integration with the landscape. I’ve yet to see a vine grow on a Murcutt house.” But Murcutt does not share Cox’s definition of landscape. Murcutt’s houses are surrounded by ecosystems, not cultivated environments. Accordingly, they sit off the ground, rather than on it.

Both architects claim continuity with Australia’s earliest architecture. For Cox, this means white settlement and the homestead. For Murcutt, it is the Aboriginal humpy. “The verandah form is fundamental to the way people lived in the country,” says Cox. “Kitchens were detached due to risk of fire, there were staff quarters, external dining areas for field workers. Homesteads were never a single pod.” The Hambrett House reflects the logic of utility, with the line of the verandah breaking to accommodate the laundry, or a wall protruding to hide the bedrooms from view. Inspired by the minimal humpy, Murcutt’s houses are isolated and contained, their interiors strictly delineated into living and service spaces.

Philip Cox has built prolifically in Sydney. He is a divisive character and his buildings – stadium, pool, casino and exhibition centre are counted among the city’s most loved and most contentious.1 Remote, inaccessible and steeped in mythology, Murcutt’s work retains the aura of perfection. His Pritzker Prize, architecture’s highest honour, venerates a portfolio of mostly private houses. While Cox was completing the Hambrett House, work on the Yulara township and resort near Uluru was underway. Joanne recalls that “drawings of Yulara were pinned up on the office walls at Lavender Bay,” and Cox affirms that “a lot of the issues and thinking in the Hambrett House went into Yulara.”

In 1985 Yulara received the national Sir Zelman Cowen Award for Public Architecture. But there is only one Northern Territory project on the Australian Institute of Architects’ National Register of Significant 20th Century Architecture. It is not Yulara, but a Murcutt house.

1. Since its opening in 1988 as part of Australia’s bicentenary celebrations, The Sydney Exhibition Centre received twelve awards including the 1989 Sir John Sulman Medal for Public Architecture from the Australian Institute of Architects (NSW). It also won a string of other awards for engineering, sustainability and conference facilities. Despite a campaign to save the centre, under the direction of the NSW Government, it is being demolished in 2014.

Credits

- Project

- Hambrett House

- Architect

- Cox Architecture

Australia

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

Source

Project

Published online: 5 Mar 2014

Words:

David Neustein

Images:

Brett Boardman

Issue

Houses, December 2013