REVIEW SHELLEY PENN

PHOTOGRAPHY TREVOR MEIN

The striking new elevation of Heide III, with the new Albert and Barbara Tucker Gallery behind. Progeny, 2004–2005, by John Meade, is seen in the foreground.

Looking over the Loti Smorgon Courtyard to the entry to Heide III, with the jagged black forms of the new gallery seen to the left. Anish Kapoor’s limestone works, In the presence of form and Untitled, are in the foreground.

The existing Loti Smorgon Gallery in Heide III, with a new opening allowing visual links to the landscape beyond. The exhibition shown is Imagine…. the creativity shaping our culture, with Lizzy Newman’s installation, You’re still making history that no-one else knew how to, 2006, seen to the left.

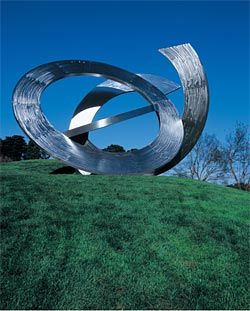

Rings of Saturn, 2005–2006, by Inge King, a major new sculpture in the Sir Rupert Hamer Garden.

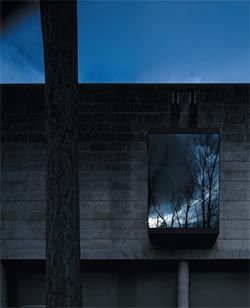

The new opening punctures the wall of the Loti Smorgon Gallery.

Looking along the length of the new Albert and Barbara Tucker Gallery with views to the Sir Rupert Hamer Garden and Inge King’s Rings of Saturn beyond. The exhibition is Meeting a dream: Albert Tucker in Paris, 1948 – 1952.

The new opening in the wall of Heide III allows a view from the foyer, through the galleries, to the framed landscape beyond.

The reconfigured Heide shop.

Heide II, by McGlashan Everist, 1963, restored by Bryce Raworth as part of the redevelopment work. The sculpture in the foreground is Sidestep, 1971, by Anthony Caro. Photograph John Gollings.

Interior of Heide II, with the exhibition New to the modern: Heide twenty five years on, which showed until late February. Photograph David Pidgeon.

The Sidney Myer Education Centre, a new building in Heide’s “colony” of places. It sits above the pasture-lawn, with Heide II seen in the distance.

The interior learning space and semi-enclosed forecourt of the Sidney Myer Education Centre, overlooking the open pasture-lawn.

John and Sunday Reed were early exponents and patrons of Modernism in Australian art and design. Their home at Heide was a centre for discussion and avant-garde ideas in the 1930s and 40s, where an awareness of the greater context of world art and literature was taken for granted. The Reeds supported and fostered young writers and artists such as Albert Tucker and Sidney Nolan, Joy Hester, John Perceval and others. They were instrumental in bringing the works of Nolan and Tucker to public attention, and they supported these artists throughout their lives, despite falling out with both in the late 40s. Some histories depict the Reeds as somewhat cloying, emotionally dependent on their association with these artists. In his introduction to Bert & Ned: the correspondence of Albert Tucker and Sidney Nolan, Patrick McCaughey notes, “The Reeds, who had appeared so cosmopolitan, so sophisticated, during the previous decade, looked increasingly provincial, locked into an anachronistic version of history, a memory of things past that was oppressive and unreal. The artists transformed themselves; the Reeds entrenched themselves in the mythology of Heide.”¹

›› The contemporary reality of Heide as a museum and as a place tells a different story. A museum of modern art and design in Australia was first envisaged by the Reeds in the 1930s and established by 1960. In 1980, they gifted it to the state for the public benefit, indicating a broad vision and a genuine desire to contribute beyond their milieu. Heide has thrived on the strength of that vision and its continuing relevance. Related to their engagement in the cultural environment was the Reeds’ sensitivity to and awareness of the physical landscape within which they lived. Their development of the estate and the agenda set by their approach are significant contributions in themselves, and the most recent works at Heide, completed last year, have been executed with an acute sensitivity to its heritage.

Heide is located in Bulleen, now a 15-minute trip north-east of Melbourne. Arrival is via a hilltop, where their original house is located and from which the land falls away to the north and west, with broad views across the Yarra River flood plain and remnant undulations of the Great Dividing Range. Although embedded in suburbia, the estate is substantial. Its access to the river, native reserves and its own landscape gives it the rarefied air of a sanctuary.

For thirty years, the Reeds occupied Heide I, a fairly typical Victorian cottage disconnected from its landscape. The Reeds’ real living place, however, was beyond the house: they played and worked in the gardens, recruiting their frequent visitors to join in; they cultivated different spaces including kitchen gardens, stands of fruit trees, open lawns and pockets of native bush. Their cultivation of the landscape was about place making, feeding the mind-soul as well as the body. By the early 1960s, they began placing sculpture in the garden, extending their occupation of it as a dwelling place.

Their support of modern art and design included architecture, and they engaged with young Modern architects such as Guilford Bell and McGlashan Everist. In 1961 McGlashan Everist was commissioned to build the Reeds’ beach house at Aspendale, and two years later their new house, Heide II, at Bulleen. This commission clearly expressed the Reeds’ sensibility. Philip Goad quotes the Reeds on their brief to the architect: they sought “the sense of walls within and extending into a garden”, and later noted, “We consider the building itself as a sculpture set in a garden, in some ways reminiscent of a maze, and we adopted a modular and open-ended plan form, capable of extension.” ² Goad also notes that they agreed to McGlashan’s suggestion to site the house “lower down on the property to take advantage of the view within the valley instead of over it.”

›› The result is an exceptional building, highly acclaimed since its completion in 1968. The essential idea of relationship with landscape, as identified in the Reeds’ brief, is manifest in the building plan, the spatial sensibility, the form, the scale, and in all of its details. You do not have to be an architect to understand this at an intuitive level: the connection from inside to out, the unravelling of spaces from the centre, and the constant awareness of the surrounding landscape is essential to an experience of the building. On approaching from outside, from any direction, the cubic forms seem to open up, revealing themselves first as garden walls, then leading to courtyards or semi-enclosed gardens, and finally to internal spaces. Demonstrating their urge to knit with the landscape, the house is also testament to the Reeds’ early vision to create a museum of modern art, with their brief for Heide II requiring that it have “a quality of space and natural light appropriate to a gallery”. The Reeds lived in Heide II for thirteen years until 1980, a year before their deaths.

Given the significance of landscape for Heide, the next architectural development was disappointing. Heide III, a dedicated public gallery, was designed by Andrew Andersons of Peddle Thorp and Walker and completed in 1993. It was closed in plan and form, appearing hermetic and bulky in contrast to Heide II, whose scale is modulated through its articulation as a series of walls. It mimicked Heide II’s main exterior materials and some details, and connected to it physically such that the two buildings were blurred, confusing the reading of Heide II and making the whole a greater mass on the site. This undermined Sunday Reed’s early conception of “a colony or a significant relationship between dwellings”, and the idea of existing in relationship with the landscape. With limited access to natural light and views, interior and exterior spaces were disconnected. Although this was common for gallery interiors, its external expression need not have been so blunt. The architecture of Heide III mistook the importance of landscape and all things Modern to the Reeds, and undermined the essence of Heide II.

Last year, the most recent developments at Heide were unveiled. These began life with an architectural design competition for a Heide master plan and a commission in 1999 for O’Connor and Houle Architecture, whose winning scheme stood out for its sensitivity to the physical and historical landscapes of Heide. Seven years later, and after a complex process, it was completed at a much reduced but still broad scope. The most obvious component of the new work is the extension of Heide III with two new gallery spaces: the Albert and Barbara Tucker Gallery and associated Study Centre, and the Andrew Myer and Kerry Gardner Project Space, with a new foyer and shop, as well as storage and loading facilities. The addition is interesting on several levels. In terms of the connection and later division between Albert Tucker and the Reeds, the bequest of Tucker’s work to Heide just before his death in 1999 appears a strong gesture of reconciliation. In relation to the development of architecture and landscape, the new work is also a restorative gesture – rectifying the aberrant original Heide III and restoring the experience of landscape as core to the estate.

The new Heide III consists of a long, narrow, zinc-clad form with jagged, abstracted sawtooth roof lights popping up above. It reads as a black, textured wall, with only the roof forms hinting at the third dimension. On approaching the building from the hilltop and winding down the drive, it appears as a sculptural element against the backdrop of the valley and hills, and conceals the bulk of the old Heide III roof behind. Close up, it embraces the new external plaza with a slight kink in alignment, leading the eye toward the entry and the mind to the walls of Heide II. Detailing is fine but not overwrought, and the precise yet uncomplicated butt joint connecting Heide II and III is refreshing. The new Project Space nestles in between new and old Heide III forms, as does a ramp connecting the galleries, distinguishing the forms internally. Virtually hidden behind the new structure are additional ancillary spaces, the only disappointment in this work: plain rectilinear and finished with natural grey cement render (a new addition to the Heide palette), they lack the fine handling of scale and proportion so evident elsewhere. Internally, the old Heide III has been altered to improve awareness of the greater context, with new light shafts and external views allowing the visitor to locate themselves according to landmark elements in the landscape. From the curatorial point of view, these are welcome and manageable connections to the world outside, and an appropriate step for Heide. Landscape is brought back to the fore and intelligent respect returned to Heide II.

Other new works extend and reinforce context as central to an understanding of Heide. A number of new garden spaces have been established including the Sir Rupert Hamer Garden, a collaboration between O’Connor and Houle and Elizabeth Peck Landscape Architect. This aims to blur the distinctions between art object and landscape, and incorporates a new sculpture by Inge King, viewed from within the new gallery and garden. The Tony and Cathie Hancy Sculpture Plaza is partly formed by the gallery. It extends the existing Loti Smorgon Courtyard and creates a substantial entry plaza – from here the new form reads most strongly as a wall leading the eye to Heide II. The Heide II Kitchen Garden has also been restored and extensively replanted. Heide II has itself been restored by Bryce Raworth, with a number of previously closed spaces now open to the public.

The Sidney Myer Education Centre, also by O’Connor and Houle, is a wholly new building. Located to the north-east of Heide II, it overlooks the open pasture-lawn and provides a dedicated space for children to learn about the arts. It directly contributes to the idea of a “colony” of places, in relationship within a landscape. It is a small, box-like building, hovering above the ground, with a main interior learning space and a semi-enclosed forecourt from which broad timber steps for access and play extend into the new Helen Macpherson Smith Garden, landscaped by Heide’s head gardener Nick Harrison. This building represents an extension of ideas, with insightful references to Heide II and Heide III and offering a “new” modernism for Heide. One contrast is its presence as a complete entity, separate from the landscape. Another is the forecourt, which also offers an abstract link. Profoundly different from the courts of Heide II – made of walls founded in the earth, open to sky and extending outward – this space is open at front and back, and carved out of the greater form. The building is clad in black lightweight metal, a link to Heide III. Although a small building, the perceived scale is slightly oversized due to the clarity of form and relative lack of articulation. However, I suspect this is temporary and its baldness will diminish as the garden matures.

The Heide first envisioned by John and Sunday Reed was a place of beauty where creative talent was to be nurtured and celebrated. After seventy years, the vision is still resonant, and their legacy is an extraordinary contribution to Australian art and design, both as a museum and as a place. The support of Modern art and architecture has grown, and the estate continues to evolve around a sensibility for landscape and relationship. Each development of the physical environment reveals something of its cultural context, and the stories are not about languishing in mythology. These most recent works extend the Reeds’ vision with sensitivity and intelligence, and affirm Heide’s undiminished vitality.

›› Shelley Penn is a practising architect. She is also the Deputy Victorian Government Architect.

››

¹ Patrick McCaughey, Bert & Ned: the correspondence of Albert Tucker and Sidney Nolan (The Miegunyah Press: Melbourne, 2006). ››

² Philip Goad, “Walls in a Landscape: the making of Heide II” from Living in Landscape: Heide and houses by McGlashan Everist, the catalogue to an exhibition curated by Goad at Heide Museum of Modern Art last year.

HEIDE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART REDEVELOPMENT, 2005–2006

Heide III Redevelopment and Sidney Myer Education Centre

Architect

O’Connor + Houle Architecture— project team

Stephen O’Connor, Annick Houle, Chris Lamborn, Jennifer Mueller, Rim Martin.

›› Landscape architect ›› Elizabeth Peck Landscape Architect.

›› Heritage authority ›› Heritage Victoria.

›› Structural and civil engineer ›› Irwinconsult.

›› Mechanical, electrical, hydraulic, security and fire engineer ›› Connell Wagner.

›› Lighting consultant ›› Electrolight.

›› Quantity surveyor

Slattery Australia.

›› Building surveyor ›› Hendry Group.

›› Builder ›› Adco Constructions.

›› Heritage advisor ›› Bryce Raworth.

›› Project manager ›› Lateral Projects and Development.

Heide II Restoration

Heritage advisor ›› Bryce Raworth.

›› Heritage authority ›› Heritage Victoria.

›› Structural and civil engineer ›› Beauchamp Hogg Spano Consultants.

›› Mechanical, electrical, hydraulic, security and fire engineer ›› Connell Wagner.

›› Project manager ›› Lateral Projects and Development.

›› Builder ›› JMA Builders, Contract Management Systems.

2005–2006 Heide Redevelopment

Redevelopment partners ›› Victorian State Government through the Community Support Fund, Australian Government through the Federation Cultural and Heritage Projects Program, Sidney Myer Fund, Helen Macpherson Smith Trust, Australian Government under its Regional Partnerships Program, Australian Government through the Department of the Environment and Heritage, Victorian State Government through the Creating Better Places Program.

Client ›› Heide Museum of Modern Art.

›› Council ›› City of Manningham.