Reasons for fix work

A northern Australian team at the end of a Survey Fix week.

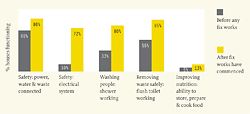

Improvement as a result of Housing for Health: Comparison of houses before and after fix works.

I asked for directions to the train station in a busy European city. A concerned local paused for careful consideration and then replied, “I wouldn’t be starting from here”.

It is difficult to determine clear directions for Indigenous housing without first defining where it is now. This paper outlines what has been learnt from over twenty years of Housing for Heath projects, discusses the last seven years of detailed data and suggests how that data offers better directions for future housing.

Housing for Health projects include the Commonwealth Government-funded program known since 1999 as Fixing Houses for Better Health. They have a nationally endorsed safety and health focus based on life-threatening safety and nine prioritized Healthy Living Practices, and have been completed in a range of remote, rural and urban Indigenous communities around Australia. Developed in 1987, the Healthy Living Practices are, in order of priority, the ability to wash children, wash clothes and bedding, remove waste water safely, improve nutrition, reduce the negative impacts of crowding, reduce the negative impacts of insects and animals, control dust, control temperature and reduce minor trauma.

Each Housing for Health project involves testing 250 parts of the houses and surrounding yards on project sites, immediate fix work to improve the living conditions, six months to one year of more major fix works, and then repeating the testing of the houses to assess safety and health improvement. Currently 78 percent of all staff employed nationally are local Indigenous people.

Recent data shows the condition of houses in project sites across the country where work has been requested (it does not, therefore, represent a random sample).1 This covers over 5,000 houses, so it describes a large proportion of the estimated 22,000 houses under Indigenous control.2 The data is obtained by using standard, repeatable tests with yes/no answers. The tests, scoring and data produced have been independently evaluated and found to be sound.3 The pattern of the results has remained constant over many years, with a slight decline in initial house condition over the last four years.

The data represents an overall failure to deliver reasonable living conditions to some citizens of Australia. The effectiveness of all levels of government, the professions, agencies, trades and building associations is measured by these results. There are three particularly important results: firstly, electrical safety is very poor, with 10% of houses being found electrically safe (assessed against the national electrical standard); secondly, in the houses surveyed, only one third of showers are working; and thirdly, only 5 percent of the 5,000 houses have a working kitchen.

The aim of Housing for Health is not to collect data, or highlight poor housing performance; it is to improve living conditions. The results, before and after fix work is completed, are shown in the graph on the next page. The budget to achieve these results varies from $3,500 to $7,500 average per house and includes all labour, transport and material costs.

These figures show poor housing function. When shown overseas, they cause immediate reaction. Within Australia, however, they rarely raise a question. The reason for this easy acceptance lies in the subtly created myth that all housing problems are caused by housing tenants. Over twenty years, the myth has had variations on the same theme: “they can’t manage Western-style housing”, “vandalism is the key housing management issue” or “Indigenous people need to be educated about how to use the house”.

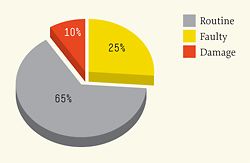

Vandalism, misuse and overuse of houses does occur, but design priorities and housing management policy should reflect the total money spent on repairing buildings. A survey of national fix work based on reports from licensed trades on all Housing for Health and Fixing Houses for Better Health projects shows the reasons maintenance work was required. Licensed trades checked 91,819 items, and fix work was completed on 63,973 of these. The reasons were in order of importance and resources spent on repair:

• Routine (normal wear and tear, routine maintenance): 65%

• Faulty (poor initial construction, incorrect product or specification): 25%

• Damaged (overuse, misuse, abuse or vandalism): 10% This shows that the bulk of the problem remains with those who design, build, maintain and manage houses.

A “standard housing cycle” model has been repeated three times in the last twenty-five years. The model begins with the aim of delivering many cheap houses today – houses immediately, rather than “housing”. As the cycle progresses, “housing” (or what amenity houses should deliver to residents tomorrow) becomes more important. The stages of the cycle are as follows:

[1] Great need – lack of housing and overcrowding is measured and considered unacceptable.

[2] Cheaper houses – national funds to provide Indigenous houses remains fixed (or is reducing in real terms), so the way to build more houses is to reduce the cost of houses.

[3] New ideas to reduce cost – this will be achieved by the introduction of new ideas, as the old ideas were unacceptably expensive. Existing design standards or guidelines are labelled excessive and inflationary. Capital cost will be the focus of the new idea, not running costs or maintenance costs.

[4] House failure – housing design, material quality and construction supervision are all reduced and housing fails.

[5] Improve standards – reviews of housing projects are commissioned to find ways to ensure the quality of housing is improved. The establishment of standards and regulation are recommended, which increase the cost of housing.

And the cycle begins again.

Poorly designed and built houses provide little safety and few health benefits to residents, and the impact on crowding in houses is usually out of sight but dramatic. For example, if a small community has twenty houses and the total community population is 120 people, an assumption could be made that the crowding level is six people per house. Say only 33 percent of those twenty houses have a working shower – as shown in the current national function rate of over 5,000 houses surveyed and fixed – then the 120 people of this community have only six houses with a functioning shower available. That means a crowding level of twenty per house to use a shower. Combine some of the other function rates (toilet, drainage, kitchen) and the reason the living environment causes ill health is clear.

House size, specifically the number of bedrooms, is still the key national measure of housing adequacy. The function of the health hardware – any part of the living environment that contributes to a person’s health – is hard to accurately assess and therefore is neither known nor considered important. This means that only part of the crowding issue is addressed.

The work of improving the living environment is critical and needs a multi-layered approach that has to be established with, not for, the local Indigenous community. There are some key aspects to this approach:

• Existing houses should be fixed immediately – there should be no housing surveys without an immediate fix of some sort.

• Houses should be built to function well – design documents, specifications, supervision of construction and testing at handover will all improve the safety and health function of the completed house.

• All housing should be maintained, not just managed – do not simply collect rent, but ensure tenants are receiving value for their rent (as house function rates improve, so do rates of rent collection).

• Houses should be better designed to ensure ongoing function, and be more economical to run and maintain.

• Consider designing and prefabricating key parts of the house to improve construction quality and maintain, if not reduce, capital costs – for example, showers, laundries, toilet areas and kitchens are “licensed trade intensive” and would be ideal parts of a house to prefabricate, leaving local Indigenous building teams free to build the less trade-intensive parts of the house.

• Encourage industry to participate in long-term partnerships to produce better house components for a wide range of environments that will be present in all types of house designs – for example, hot water systems, stoves, lights, taps, and heating and cooling systems.

These are complex issues for debate and discussion. But we should work towards a prescription for which way, or ways, Indigenous housing should head. I have several recommendations for action.

Firstly, we should aim for better housing – by 2010, any Housing for Health project conducted in Australia should achieve a result that shows 75 percent of all houses reach a function score on all Critical Healthy Living Practices before any fix work commences. Secondly, there should be continued use, promotion, expansion and improvement of the National Indigenous Housing Guide.4 It should become the repository of past experience and future direction that can be used to improve Indigenous housing.

Thirdly, I suggest establishing a National Indigenous Housing Standards Forum to assist with improving housing nationally. A version of this ran in South Australia for around eight years in the mid-to-late 1990s and greatly improved the quality of houses in the state. A national forum would work with Indigenous people to improve the quality, quantity and performance of housing, and to advise/consult with governments, professions, the building industry and general industry.

Improvement of the living environment of Indigenous Australians is possible and should happen today.

Paul Pholeros is an architect and director of Healthabitat. He is the national program manager of Fixing Houses for Better Health and Housing for Health projects and is a member of the Australian Institute of Architects Indigenous Housing Taskforce. This is an edited version of the paper he presented at Which Way? Directions in Indigenous Housing in 2007.

1. For regularly updated data, see the Healthabitat website: www.healthabitat.com

2. Pricewaterhouse Coopers, “Indigenous Community Housing Organisations (ICHO) Housing Management Breakdown”, in Living in the Sunburnt Country. Indigenous Housing: Findings of the Review of the Community Housing and Infrastructure Program (Canberra: Department of Families and Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, 2007), p.62.

3. SGS Economics and Planning in conjunction with Tallegalla Consultants, “Occasional Paper 14”, Evaluation of Fixing Houses for Better Health Projects 2, 3 and 4 (Canberra: Department of Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, 2006).

4. The third edition of the National Indigenous Housing Guide was published in 2007 by the Australian Government. Endorsed by all states, it is reviewed every two years.