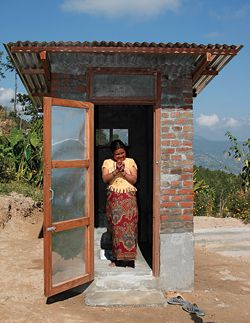

One of fifty-two new toilets by Healthabitat in Bhattedande, Nepal. Photograph Srijan Bajracharya.

Students at the Ngari Community High School by Emergency Architects Australia. Photograph Vicki Hon Briggs.

The Ngari school was built by the entire community, including Davinia Solo of Paelongge village. Photograph Vicki Hon Briggs.

The girls dormitory at Ngari. Photograph Richard Briggs.

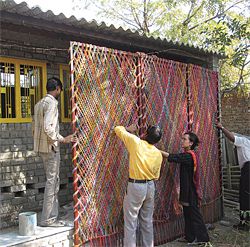

Installing a screen at a bholu preschool by Architects Without Frontiers, Ahmedabad, India.

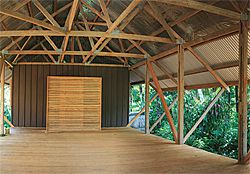

Students work with Dr David O’Brien to build a prototype sala in Nang Rong district, north-eastern Thailand. Photograph Hamish Hill.

Above and this: Construction of the Charles Boyu Elementary and Junior High School in Ganta, Liberia, by Finley Pitt for UNICEF. Three buildings are located beneath a single floating roof, with the whole designed as a gathering place for the community. The school is one of a number planned as part of the Learning Along Borders for Living Across Boundaries (LABLAB) project. Photographs Finley Pitt.

Finley Pitt (right) at the school with the President of Liberia, Ellen Johnson Sirleaf. Photograph Nicholas Ogburn.

PETER JOHNS DISCUSSES A RANGE OF HUMANITARIAN AND AID WORK BEING UNDERTAKEN OVERSEAS BY AUSTRALIAN ARCHITECTS.

Australian architects work all over the world on humanitarian projects for nothing or next to nothing. These projects commonly come about because architects are overseas and see a need, or are approached by NGOs in Australia who know of a project that could do with some expert assistance.

This article briefly surveys the recent and current work of several groups and individuals, working in Papua New Guinea, East Timor, India, Thailand, Nepal, Liberia and the Solomon Islands. The way projects are dealt with varies wildly. Some architects are paid; most are not. Some work on the ground, while others work remotely. Some vet projects carefully, while other architects discover projects on their travels and stay around to lend a hand.

Individual architects have been helping out for free on projects forever. But the phenomenon of the architectural aid organization has only recently hit Australia. Most of the main organizations have been established for ten years or less. They tend to work around one another, respecting their differences. Rarely do they compete for pro bono projects – there are just too many to go around.

Immediately after the Solomon Islands earthquake in 2007, Emergency Architects Australia (EAA) sent a rapid assessment team to survey damage. A series of safe building workshops followed. They were soon approached by the Solomon Islands Department of Education, Human Resources and Development (MEHRD) to design an exemplar school for the Western Province. The result was the Ngari Community High School on Ghizo Island. After consultation with the community, and learning about local techniques and materials, documentation was performed in Australia. EAA maintained a presence on site through the two stages with stipendiary project facilitators, who sourced materials and supplemented locals’ construction and materials knowledge with techniques that would enable safer construction in the future.

The Ngari school was the model for 108 other schools now being built throughout the province by Recovery Action and Rehabilitation Project (RARP), a local NGO working with UNICEF. The project has had other effects, too. The cross-bracing and window design skills learnt by the local tradespeople are now being applied to other buildings on Ghizo Island. EAA is especially proud of the window hatch design developed with the community – it enables just the right mix of air, light and privacy through the use of louvred shutters.

Architects For Peace launched its pro bono referral service in 2006, focusing on local community groups. It doesn’t do the work directly, instead matchmaking member architects to community groups around Melbourne. The scheme works and demand is building. Some of these local NGOs represent communities in East Timor and beyond. These projects have proven trickier than the norm, with local architects trying to work remotely from Melbourne. President Eleanor Chapman says, “There are difficulties translating the local model overseas.” However, they will keep developing the model.

It does seem that having an architect living in the community contributes to the likelihood of getting a building out of the ground. But it makes it a whole lot more expensive and brings up insurance, registration and language issues. It also reduces the available pool of architects to those able to leave their local jobs for a few months.

In Ahmedabad in India, Architects without Frontiers (AWF) has been building preschools (anganwadi) since 2008. Every year volunteers pay to travel to India to design and build the next bholu, named after the company that set up the connection with AWF. The ninth bholu has just opened. Over the years, AWF will build or renovate sixty-six anganwadi in the slum communities of Tekra. Each is briefed separately as needs and context vary. So that the next group of architects has a head start, AWF is assembling a handbook of useful information gleaned from previous trips. Funding for several bholus came from the City of Melbourne via the profits from the EcoEDGE 2 conference held in 2008. AWF is seeking volunteers for the next anganwadi building season now.

With ongoing programs in India and elsewhere, AWF is re-evaluating its strategy to avoid over-stretching its resources. It is taking on fewer new projects, evaluating them more carefully and trying to “home in on the Asia-Pacific area”, where it has prior experience. There is also increasing demand for its services within Australia, particularly in remote northern Indigenous communities.

Paul Pholeros of Healthabitat first heard about the plight of the Nepalese village Bhattedande from his wife, who was working in the health sector in the area. This low-caste community was responsible for a disproportionate number of hospital admissions. The 800-year-old Bhattedande was unable to cope with its dense population of 450 and sanitation was the big issue. Learning that the village had already identified this as a problem, and had set up an environmental committee, Healthabitat approached with an offer to assist based on their work in remote Indigenous communities in Australia. It soon became obvious that the health problems in the village were not solely due to the lack of toilets. A lack of suitable timber meant that green wood was being used for cooking fuel in badly ventilated houses. The smoke was affecting the women and children responsible for preparing the food.

Healthabitat proposed a waste removal and recycling solution that provoked many questions from the community. The toilets were the easy part – what was harder to negotiate were the proposals to use sewerage for biogas production and irrigation. “Won’t cooking with shit just worsen our health problems?” “Won’t it explode?” “My buffalo might stand on the biogas dome and fall in.” After demonstrations and meetings in the square, the community came onside and with seed money from the Healthabitat directors, the project began. Fifty-two toilets have now been hand-built, with 30 percent funding from Healthabitat and the remainder from donors. Yes, they could have gotten it all prefabricated in China and dropped it in, but that would cut the locals out of the technology transfer and employment. The architects no longer need to visit as the team is fully Nepalese and a local health NGO has taken the project over. The scheme is now rolling out into other villages.

At the University of Melbourne, Dr David O’Brien works with students on projects in Thailand and Papua New Guinea. On alternating years groups travel to villages in both countries. They live for a while with the locals and learn the way things are done. At the same time they participate in construction projects designed by the group from two years before. O’Brien’s students identify and use traditional building methods, integrating new materials where relevant. At Ban Nong Thong Lim in North East Thailand, timber is unavailable due to deforestation. Concrete block is seen by many as the answer. It also allows houses to look more like those on TV. Fences and asbestos cement tile roofs are becoming popular for the same reason. The houses are dark inside and airless as windows are expensive to install in these walls. This combination of changes is fragmenting communities into isolated fenced households. The prototype project is an open-sided sala – a waiting pavilion next to a community health unit. It was built using traditional post-and-beam techniques, but with an available material – steel. This year students and the community will develop the ideas from the pavilion into models for more sustainable and healthier housing.

Students from the University of Melbourne are also working in the high country of Papua New Guinea, on a village that outwardly looks very sustainable. Except that there is little employment and no safe drinking water, thanks again to industrial-scale deforestation. They were invited to help villagers “value-add” to sustainably grown local timber. Some of this timber will be used to build houses in the village in December. Corrugated steel will be used instead of traditional thatched roofs. Gutters will flow to new rainwater tanks, providing drinking water. O’Brien says their challenge was to build something that “ticked many boxes”.

While the students run the building programs, locals interested in lending a hand are encouraged to do so. They learn from one another and build trust, and the processes can continue after the students leave. “It’s a technology transfer – both ways.” O’Brien believes in building long-term relationships with specific villages, rather than trying to cover too much ground. If the buildings work and are accepted into one village, “others can borrow from it”. All the groups acknowledge the benefits of working with specific communities over time, rather than dropping in, doing the work and leaving forever. As the quality of participation improves, so does each project.

Architects and graduates working on these overseas projects tend to be young and working for themselves or to have taken time out from a larger practice. They are usually volunteers and pay their way. Most are provided with accommodation, and some may get a stipend to cover their living costs. Only one respondent was being paid a full-time salary – Finley Pitt working for UNICEF on educational facilities in Liberia’s border communities. Rarely do large Australian practices support these architects or offer their own time. Dr Esther Charlesworth from AWF puts this down to a general lack of corporate social responsibility in Australia – despite the talk, the emphasis is still on short-term cash flow and the single bottom line. Charlesworth points out that both the legal and medical professions have requirements for practices to be involved in pro bono projects, but not architecture.

The architectural process has proven its value in disadvantaged and disaster-struck communities. Maybe it is time for a profession-wide rethink. Some architects say pro bono work is dangerous to the profession because it does architects out of a job and it values their work at nil. It is perhaps better thought of as an in-kind donation to a project – rather than donating to the Red Cross via an online button, this is a donation of professional services to worthy projects for people in need. The less spent on consultants, the more there is left for the building. It is also a way of demonstrating to a broader community that architecture does matter.

And what of design as it is usually published in these pages? Do these projects need to be beautiful to be worthy of attention in our eyes? I don’t think Paul Pholeros would think so – for him the basics need to be right first. But the work of many of the others places great importance on the quality of the building’s design, as long as it is informed by local ways. The building’s beauty in the eye of the villager is an important element in the pride a village has in a project.

Peter Johns is a member of Architects for Peace and Emergency Architects, and runs butterpaper.com.

Further information can be found at

www.architectswithoutfrontiers.com.au

www.healthabitat.com

www.abp.unimelb.edu.au/abpgallery/thai-project

www.openarchitecturenetwork.org/projects/2700

www.architectsforpeace.org