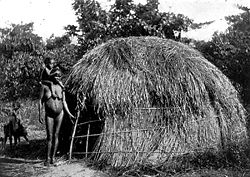

Dyirbal language group blady grass dome (midja) constructed for rainy and windy weather, Tully River c.1901.

Carroll Go-Sam discusses three design paradigms developed over the past thirty years, and the effects they have on Indigenous housing.

How do the different approaches to understanding the variety of Aboriginal domiciliary behaviour inform design processes? Three principal design paradigms have developed over the past three decades – cultural, environmental health and housing-as-process. All have had notable successes and failures, worthy of close examination if we are to refine a model and translate it within architectural practice.

This essay outlines the three models and their effects on housing, with a particular focus on cultural design. Woven through the discussion are examples drawn from my own work, from personal experiences, and from my own cultural group, the Dyirbal, whose country is on the Tully, Herbert and Wild Rivers in the North Queensland area.

Cultural Design Paradigm

Three-bedroom self-constructed house, built c.1969 at Wondecla, Herberton, by Peter Freeman. It is the residence of Lillian Freeman, maternal aunty of the author.

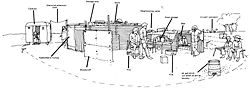

Study by Julian Wigley of a self-constructed camp layout in the Mt Nancy town camp, Alice Springs, c.1976. From Heppel and Wigley, 1981, p.136.

Drawing by Julian Wigley of a cookhouse unit and bower shades, with a timber floor platform located in a yard space near a house used during rainy periods. From B. Wigley and J. Wigley, “Community Planning Report: Barkly Region”, prepared for ATSIC on behalf of the Jurnkurakurr Aboriginal Resource Centre, 1990, p.58.

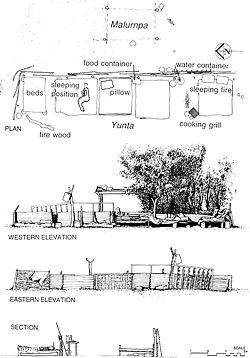

Drawings by Cathy Keys documenting a Warlpiri yunta in a jilimi (women’s residence) in Nyirripi, around 350 kilometres west of Alice Springs. From Cathy Keys, “The Architectural Implications of Warlpiri Jilimi”, PhD Thesis, University of Queensland, 1999.

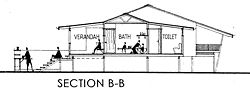

House designed for the Gregory Outstation in north-west Queensland by Deborah Fisher and Carroll Go-Sam, 1998. From Paul Memmott and Associates and Deborah Fisher, “Gregory Outstation Design Development Report” prepared for Project Services and the Bidunggu Aboriginal Corporation, 1998.

An example of a concrete block house provided by Tangentyere Council and designed by Jane Dillon and Mark Savage for Alice Springs town camps between 1984 and 1986. The design is characterized by extensive verandah and sleep-out areas for external activities and visitor accommodation.

Single men’s painting camp at Papunya.

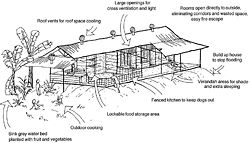

Drawing by Simon Scally of houses designed by Build Up Design and built in Arnhem Land outstations for the Bawinanga Aboriginal Corporation.

Since the 1970s successive researchers and architects have studied and analysed the domiciliary behaviour of Aboriginal self-constructed shelters and settlements, in either traditional, sedentary or fringe camps. These camps, organized and constructed by their residents, are the places where customary lifestyles are practised and learned. They reveal a clear cultural fit between the settlement type, the distribution of structures and the activity patterns contained within. The cultural design paradigm draws on this work and has been adopted and developed by a range of architectural practitioners since the 1970s.

The cultural design paradigm uses models of culturally distinct behaviour to inform definitions of Aboriginal housing needs. Its premise is that to competently design appropriate residential accommodation for Aboriginal people who have traditionally-oriented lifestyles, architects must understand the nature of those lifestyles. Culturally distinct behaviour can involve typical diurnal/nocturnal behaviour patterns for different seasonal periods, distinct types of household groups, forms of approach and departure to domiciliary spaces, external orientation and sensory communication between domiciles, sleeping behaviour, cooking behaviour and use of hearths, characteristic uses of storage for artefacts and resources, and structured socio-spatial behaviours. Knowledge of customary behaviours also increases understanding of the needs of groups who have undergone cultural changes, including those in rural, urban and metropolitan settings, by helping to identify those aspects of their customary behaviour that have been retained and those that have changed, and the impact on housing.

This approach, however, is not to be embarked upon by the misinformed. There have been considerable successes, but it is also fraught with misinterpretation. History shows us bold designs that were sometimes ill-considered and often misguided – largely because designers failed to detect overriding cultural imperatives, resulting in domiciliary stress, frustration, strong rejection or abandonment of houses.

Indigenous housing organizations, managed and operated by residents of urban, remote or rural townships, have also engaged architects to formulate methods that support cultural imperatives. One of the earliest portfolios of work exemplifying this approach is Julian Wigley’s work in Alice Springs during the mid-1970s. This included helping to establish Tangentyere Council, an umbrella Aboriginal organization that has successfully serviced eighteen of Alice Springs’ town camps and is something of a benchmark in Aboriginal housing design and practice. One example is a 1976–77 house design by Wigley, a permutation of a generative design approach based on a rectilinear grid with a core of service rooms, which allowed for Aboriginal adaptation over many years. It was a design response to the mass housing briefs of the 1970s and 80s, developed for needy communities with limited capital works budgets.

Another approach to the cultural strategy has been elaborated by Paul Memmott. This decentralized the essential components of a house, with design stages allowing different components of the architectural fabric to be adapted over time. The first step of the design process is to observe the subdivision of Aboriginal domiciliary space and behaviour in vernacular settings, including night/day, dry/wet, cold/hot and gender-specific distinctions. Then a design is generated, with different types of structure, form, materials and enclosure for different activities and times. The result is a “house” as a set of separate structures, combined with other site elements and services.

In the mid-1980s Memmott was contracted by Tangentyere Council to evaluate its housing stock. He applied the cultural design paradigm in analysing approximately 120 designs in the Tangentyere portfolio. This work, along with experience gained with Central Australian projects throughout the 1990s, highlights one of the many design innovations undertaken by architects in Central Australia in the 1980s – trying to address the negative impact of the sharing ethic on environmental health and security. Items such as veranda seats, kitchen tables and seats, and stainless steel wash troughs as baby’s baths were designed as architectural fixtures and security measures, like “fridge pantries”, were provided. Being fixed to the house, these items were not transferred and could not become subject to obligatory sharing rules.

Jane Dillon and Mark Savage managed Tangentyere Design during the 1980s and developed a design approach in response to the town campers’ architectural conservatism. This raises the dilemma of the appearance of houses versus the realities of the clients’ lifestyle. Many Aboriginal clients may resent any housing that deviates from the local white standards of rural or urban housing. Behind this reaction is the understandable desire to achieve equality, to be accepted, to have some modest but recognized status and not to be ridiculed.

Indeed, the provision of anything but a conventional house may be regarded as an insult. This is demonstrated in Morel and Ross’s examination of housing in the early 1990s at Mutitjulu. Here the use of large aluminium roller doors for the house entry attracted a great deal of negative comment – householders complained about draughts, that the doors rattled and creaked, and that they were too heavy to manipulate. The appearance of the doors also drew strong criticism – “good for garages but not houses”. One householder said, “You’re a person, and I’m a person, and that [pointing to his house] is an elephant house.” (He had seen elephant pens with large door openings at Taronga Park Zoo.) The conservative attitude of Indigenous clients is not something to be arrogantly dismissed by either architect or housing administrator. Service agencies should respect the client and work with this dilemma. The individual circumstances of the architect/client relationship must dictate the extent to which the architect should attempt to demonstrate any logical and obvious incongruence between the client’s needs and the design solution they request. The second part of this paradox is that clients may retain culturally unique norms of behaviour when they move into new conventional houses. One challenge, then, is how to design a house which appears to be conservative, but which suits the culturally specific lifestyle. Housing administrators also need to recognize that culturally specific behaviours will impact housing management systems and any mismatch in this field may result in tenancy failures. Not considering cultural needs, at both housing design and management levels, may ultimately result in a charge of indirect discrimination.

The story of my elderly aunty Lizzie Woods, respectfully called Nanna Liz, illustrates this point. Nanna Liz – who is estimated to be 94 years old, lives with her caretaker son, is wheelchair-bound and suffers from dementia – has been served with an eviction notice by the Aboriginal-controlled Cairns District Regional Housing Corporation. The reason for eviction, presented in an article in the Courier Mail on 25–26 August, is repeated house damage due to the drinking lifestyle of Nanna Woods’ relatives. The newspaper reports that “up to 25 people stayed and partied at the house, where $90,000 had been spent on maintenance in four years”. But why is the elderly, wheelchair-bound occupant, who is not causing the asserted damage to the house, being made homeless? Why is this an act of last resort by the Aboriginal housing authority? The high occupancy of Nanna Liz’s house is the result of a number of circumstances: kin obligations; demolition of the local housing association’s old housing stock, which rendered former occupants homeless in a small community with few houses to rent; vexatious and distrustful relationships, resulting in poor communication between the regional housing body and extended kin. Some of the additional residents are former campers from the local Ravenshoe Aboriginal Reserve, removed by the local Shire Council. Many of the campers are ineligible to be primary leaseholders due to their dysfunctional lifestyles. The situation has resulted in the excess housing occupants returning to mullenbarra (riverbed) camping.

This case illustrates the nexus between the socially disruptive lifestyles of extended kin and their negative impact on surrounding households, including the innocent leaseholder. Antisocial behaviour is often dealt with by eviction, rather than through mediation or in-depth consultation or even programs with extended kin households to modify their behaviour. In such circumstances, welfare housing can be perceived negatively by Aboriginal residents due to its tenuous nature, and it is fraught with conflict between family members and housing authorities. The causal relationships between antisocial behaviour and the perceived destruction of housing stock are currently under-studied or sidestepped in housing research. More research is needed to see if damage is due to negligence or component failure, along with the impact of large household occupancy and associated problems. When I worked in Central Australia in the 1990s, the more progressive Aboriginal housing corporations implemented social behaviour programs – for example, Tangentyere Council’s Mwerre Anetyeke Mparntwele (Sitting Down Good in Alice Springs). A holistic approach to housing may require this.

The cultural design paradigm concerns “targeted service delivery”. In contrast, a mainstream service, providing a blanket service to the general public, may inadvertently disadvantage a cultural group due to conflict with their customary values, practices and obligations. Between this extreme and “targeted service delivery” is “ethno-sensitive mainstreaming”, whereby mainstreaming is modified by some culturally specific techniques.

Cultural design has been taught, researched and applied from within the Aboriginal Environments Research Centre (AERC) at the University of Queensland. The work of two of the AERC’s doctoral graduates, who are also architectural practitioners, demonstrates elements of this approach at its strongest. Shaneen Fantin’s work dealt with the relationship between housing design and avoidance behaviour and sorcery in the Yolngu people of Arnhem Land, while Catherine Keys extrapolates design strategies from a consideration of women’s domiciliary camps or jilimi, built and occupied by the Warlpiri people of the Northern Territory’s central west.

Fantin’s extensive thesis of avoidance and its socio-spatial implications for design can be extrapolated to other groups observing kinship rules. For example, particular behaviours regulate relationships between men and their mothers-in-law and women and their brothers. Both “poison relations” and sorcery can form important design considerations. Sorcery can have a debilitating and stressful effect on house residents, specifically in terms of the location of wet areas. If these are removed from the main house, people become highly concerned with monitoring access to personal belongings and ablutions that might be obtained to perform sorcery. Movement at night, especially for children, is restricted due to beliefs about malevolent spirits. As a result, people often prefer not to have toilets and showers remotely located. This is one of the key contradictions to the National Indigenous Housing Guide and Environmental Health Standards for remote-area housing in the Northern Territory, although separated wet areas are not rejected by all. These beliefs are not restricted to the Yolngu; they occur in varying degrees across the continent. Within my own community, the Dyirbal, beliefs about unseen spirits affect camping behaviour, nocturnal movement and the occupation of housing.

Keys’ study concerns ritualized mourning and the pervading presence of multifaceted sorry camps at Yuendumu. These camps were used more than other traditional camp forms. The occupation of mortuary camps peaks due to the death of a housing resident, when mourners temporarily reside in jilimi, with the need dwindling as occupants return to their houses over a period of weeks and months. The relocation to self-constructed architecture by mourners is not a dismal proposition. However, it was necessitated by the absence of other alternative accommodation, stressing the limited available vegetation resources and increasing the reliance on imported building materials. Again there are similarities with other communities. When a member of the Dyirbal community at Murray Upper dies, they are buried with all their possessions, regardless of economic value – for example, boat, television or VCR. This largely relates to the overriding belief of the connectedness of the seen and unseen worlds, along with the desire to break any connection between the deceased and the living.

Elsewhere Keys has presented significant research findings about connections between Warlpiri ancestral dreaming and sleeping orientation, which permits receptivity for “good dreams” and wards off sickness. The preference to orientate jilimi structures on an east–west alignment is counter to much of the climatically responsive requirements taught in architectural environmental science for the southern hemisphere.

Environmental Health Design

Environmental health design, the second paradigm, emerged from the Nganampa Health Council in Alice Springs, which services the Anangu Pitjantjatjara homelands in the north-west of South Australia. Between 1986 and 1987, Nganampa, in conjunction with the South Australian Government, sponsored a review of environmental and public health in these homelands. The resulting document has become known as the UPK Report. In this, architect Paul Pholeros combined his skills with those of doctor Paul Torzillo and anthropologist Steph Rainow to develop an understanding of the critical relationships between poor Aboriginal health and housing technology performance. A seminal, similarly multidisciplinary project, involving an architect and a doctor, was carried out at Wilcannia around 1974–75 by architect Ken George.

The Nganampa work was the first to systematically isolate and causally link complexes of health problems with sets of design features. The “healthy living practices” identified in the UPK Report generate ten principles of housing design that will allegedly improve health standards: provision of washing facilities for people, washing of clothes and bedding, waste removal, promoting good nutrition by ongoing appropriate food storage hardware, reduction of crowding, separation of dogs and children, dust control, temperature control, reduction of traumatic injury by minimizing environmental hazards, and effective management of housing stock.

Pholeros, Torzillo and Rainow have produced further important publications on this work, culminating in The National Indigenous Housing Guide, commissioned by the Commonwealth, State and Territory Housing Ministers’ Working Group on Indigenous Housing. Their methodology has been practically applied across the continent through a large-scale ATSIC project, Fixing Houses for Better Health.

Utilizing considerable data from remote and rural housing in four states, Pholeros effectively tackles myths about Indigenous housing, which are often given as reasons for not repairing health hardware, or as arguments against replacing housing stock. This data objectively quantifies the condition and function of large amounts of housing infrastructure, particularly health hardware that is essential for healthy living practices. This is an undeniable strength of the health paradigm. If the cultural paradigm is the vehicle driving resident imperatives, this is the much needed mechanic.

Despite some contradictions between the methods advocated by proponents of the cultural design and environmental health paradigms, these approaches should be complementary. The challenge for designers is to find solutions that address overriding cultural concerns while also responding to the causal links created by poor environmental health. Both approaches have to be flexible enough to achieve the best outcome for the resident. Indigenous perceptions of what causes illness need to be incorporated – if ill health is not understood as connected to living practices, it is a considerable barrier to achieving improved health outcomes.

Housing as Process

Together, these lead to a third architectural paradigm, the housing-as-process philosophy, which aims to firmly situate housing design and provision within the broader framework of an Aboriginal community’s planning goals and cultural practices, as well as its socioeconomic structure and development. A fundamental aspect of this approach involves turning design attention to the community’s housing management capacities, and thereby ensuring that all technology is locally sustainable. Design consultants need to ensure that they consider the limitations of local conditions and the community’s capacity to financially and physically maintain and repair housing stock.

Top End architect Simon Scally’s work on the outstation at Maningrida clearly illustrates the advantages of a local umbrella organization proactively leading the housing delivery process in conjunction with an informed consultant. The problems encountered in remote delivery, although pervading, were circumvented by rejecting high-cost, high-maintenance, high-management systems. The housing-as-process philosophy is considered more systematically as a design methodology by Geoff Barker, who argues that housing must be environmentally and culturally sustainable as well as technologically sustainable. Barker provides the much-needed reflection that achieving positive change in community health and wellbeing through housing goes beyond the architecture of design.

Alison Anderson, former ATSIC Commissioner, has proposed a formula for sustainable Aboriginal housing which draws on international development experiences and overlaps some of the approaches to housing-as-process outlined above. The key factors are (i) participation – ensuring the active participation of both men and women, (ii) consultation – supporting both the traditional owners and the residents who use and own the housing to make the key decisions concerning the housing, (iii) choice – helping to find technology that is appropriate to the community and not the donor, (iv) training – equipping and training communities to operate, maintain and manage their new housing and infrastructure technologies, and (v) demand-driven – ensuring that projects match the true demand of the people who will use them.

Conclusion

Effectively reconciling these paradigms and approaches to create a complementary design process is a key challenge, but it should be a priority for contemporary practitioners.

Carroll Go-Sam is a graduate in architecture with Paul Memmott and Associates and a researcher at the Aboriginal Environments Research Centre at the University of Queensland. She was a member of the Australian Institute of Architects’ Indigenous Housing Taskforce. This is an edited version of the paper she presented at Which Way? Directions in Indigenous Housing in 2007, and is based on the introduction to Take 2: Housing Design in Indigenous Australia, which she co-wrote with Paul Memmott.

References

- Alison Anderson, “Making it work – New Ideas to Sustain Communities” in Community Technology: International Conference on Governance and Developing Communities (Centre for Appropriate Technology and Remote Area Development Group, Murdoch University, 2001), pp.6–8.

- M. Heppell (ed.), A Black Reality: Aboriginal Camps and Housing in Remote Australia (Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies, 1979).

- M. Heppell and J. Wigley, Black out in Alice: A History of the Establishment and Development of Town Camps in Alice Springs (Monograph 26, Canberra: Development Studies Centre, Australian National University, 1981).

- Catherine Keys, “Unearthing Ethno-Architectural Types” in Transition, 1997, pp.54–55.

- Paul Memmott, “Aboriginal Housing, State of the Art (or non-State of the Art)” in Architecture Australia, June 1988, pp.34–47.

- Paul Memmott, Racism, Anti-Discrimination and Government Service Delivery in Aboriginal New South Wales. A discussion paper for the Anti-Discrimination Board, Attorney-General’s Department NSW, 29/03/90.

- Paul Memmott (ed.), Take 2: Housing Design in Indigenous Australia (Royal Australian Institute of Architects, Canberra, 2002).

- P. Memmott, S. Long, S. Fantin and E. Eckerman, Post-Occupancy Evaluation of Aboriginal Housing in the N.T. for IHANT: Social Response Component (Brisbane: AERC, University of Queensland, 2000).

- P. Morel and H. Ross, Housing Design Assessment for Bush Communities (Alice Springs: Tangentyere Council, NT Department of Lands, Housing and Local Government, 1993).

- P. Pholeros, S. Rainow and P. Torzillo, Housing for Health: Towards a Healthy Living Environment for Aboriginal Australia (Newport Beach, New South Wales: Healthabitat, 1993).

- Healthabitat, The National Indigenous Housing Guide: Improving the Living Environment for Safety, Health and Sustainability (Canberra: Commonwealth, State and Territory Housing Ministers’ Working Group on Indigenous Housing [Australian Department of Family & Community Services and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission], 1999).

- P. Read (ed.), Settlement: A History of Australia Indigenous Housing (Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press, 2000).

- B. Wigley and J. Wigley, Black Iron: A History of Aboriginal housing in Northern Australia (Darwin: Northern Territory National Trust, 1993).

For a fuller list of references see the proceedings of Which Way? Directions in Indigenous Housing, available from the Australian Institute of Architects.

Source

Archive

Published online: 1 Sep 2008

Words:

Carroll Go-Sam

Issue

Architecture Australia, September 2008