Sam Jacob

Image: NZIA

Tania Davidge: I’m interested in your take on context. It differs quite radically from a critical regionalist perspective or an architectural approach that begins with site. Can you reflect on how context figures in your work?

Sam Jacob: There are so many ways of looking at context. There are the traditional ways in relation to site and orientation and sun path; there is the environmental context; and then there is the urban context, which has a whole range of issues attached to it that have to do with attitudes toward the city. Certainly, in Britain this is often to do with heritage and conservation and townscape. But I think the thing that distinguishes our approach is more to do with cultural context, a cultural reading of context. What does it mean or where did it come from? What are the competing stories?

Although our approach may also involve issues to do with climate and environment, to do with massing, or to do with a relationship to neighbouring buildings, it’s always to do with a cultural reading. And this comes out through the development of narratives specific to each project. Those narratives come from place. They also come from use, the way in which different forms are present on the site and the way in which all of the different forces that are present in the site intersect. This intersection is not always happy; these forces may well be at odds with each other.

Context is something from which you begin from and for us context is a cultural thing first of all.

TD: Architects understand narrative from an architectural perspective, drawing on the history of the architectural canon. The non-architects who use buildings interpret them in another way, sometimes very differently. This is an interesting issue when dealing with narrative. How do you view these multiple perspectives in your work? Do you look at the end-user differently to an architectural audience?

SJ: I don’t think of it as so specialised. I think all buildings, all design, have so many ways in which they can be understood – from a historical point of view, a sociological point of view, an ideological point of view. For me, both in terms of looking and understanding and also in terms of making, it’s often about trying to read those multiple ways in which something exists in the world and trying to create something that exists in the world in multiple ways. It’s not only about our discipline’s history, but it is; it’s not only about a social project, but it is. Always, our ambition is to operate on those different levels.

There are a lot of layers in the way we explain a project but also in the work there are a lot of literal layers – the layering of the facades, the way two-dimensional elements become screens. That is an interesting way of thinking about it as well. It’s about seeing one thing through another, through another, through another. It’s about the relationship of all these different meanings. In some senses that might be a different way of understanding what became known as post modernism in architecture. Post modernism in other fields is much more to do with the relational idea of meanings and symbols, whereas in architecture we became incredibly fixed.

TD: More formal? More about aesthetics?

SJ: Yeah. Like, here is the joke – do you get it? Rather than exploring a more amorphous, more fluid, idea of what meaning might be. That’s the thing that interests me.

TD: Your work, in some senses, is ‘staged’. There is something performative about the ‘stage set’ that the work creates. What is your interest in performativity?

SJ: There are a couple of ways of thinking about this. On the one hand, there is something about the way that architectural design brings things into the world that is definitely performative. It takes an idea and it acts it out. In that sense you can understand it as a theatrical act. On the other hand, if you look around the city you almost can’t imagine any other way to live. Streets, houses, offices, schools – it feels inevitable but it’s completely artificial. Thousands of years of human culture distilled into these ways of organising ourselves. Of course, this is partly architectural but it’s much more to do with society and culture and economics.

A drawing of Southwark, London, depicting relics found within the area to convey a sense of time as well as space.

Image: Sam Jacob

So in some sense, by amplifying the artificiality involved in design, it’s a way of saying there are alternatives. By describing it or thinking about it as a performance rather than a natural phenomenon, it allows a project to be critical of itself – to suggest doubt. Do we really believe in houses? Of course we do. But do we realise that they are not real? We’ve made them up.

TD: That the idea of ‘home’ when it is simply aesthetic is just something that we are comfortable with.

SJ: Exactly. That is to say we can understand things as much as stories as they are physical, legal, economic units. That is the other aspect to the theatricality.

TD: I’m interested in your take on play. Your work can be seen as playful. It has elements of the satirical and ironic. I was wondering if you consider play and how it figures across your work.

SJ: It’s not directly play. It’s a very serious attitude – perhaps, very serious play. It’s to do with playing with ideas, playing with typology, playing with possibilities. To use that to unlock some of the ways in which architecture, the building industry and planning is professionalised. In the way that it has become professionalised it has lost a lot of its potential and its power. Life is much more to do with play, in its grand sense, than it is about fixed definitions. The work is a play against the world of professionalism. It’s about exploring options, thinking through the possibilities in relation to the present circumstance.

TD: You mention that design is an imaginative tool and the A Clockwork Jerusalem exhibition for the 2014 Venice Architecture Biennale in the British Pavilion is interesting in relation to this idea. Because of the way Rem Koolhaas framed the Biennale in relation to the project of modernism, the exhibition feels like a project that needs two parts. The first, A Clockwork Jerusalem, is a kind of romantically nostalgic presentation of the utopic visions of British modernism post World War II. I was wondering if you imagine a second part to the exhibition. What do you imagine is the visionary project of today?

SJ: That’s a good question. We hope there is going to be a part two; we are trying to sort it out. What we were looking at in A Clockwork Jerusalem is not architecture and planning setting out its visionary projects. We were much more interested in where those ideas originated and where they ended up. Those ideas don’t come from architecture; they don’t come from the professions. They come from outsider artists, from journalists turned urban revolutionaries, from novelists, from political designers, and they end up with photographers and musicians and filmmakers and writers. Those are the ways in which we as a culture think about what the problems are, how we need to approach them and what the dreams that we want to manifest in the world are.

We ended the show with the same question that is at the beginning of Ebenezer Howard’s book Garden Cities of Tomorrow: “The people: where will they go?” Howard was talking about the Victorian city, the problems with the city and the problems with the country, and putting forward the new invention of a city in the country. We are interested in the way people thought through these types of scenarios. Often through writing novels – science fiction novels – going back into the past to invent the future to then make a new kind of present possible. So for part two, if it comes off, we will be writing scenarios, science fiction scenarios, about the near future that will be explorations of possibilities in contemporary phenomena. For example, if you think of the garden city – what would you get if you crossed the rural and technological? How can you exist in the landscape with your mobile phone?

TD: Imagine the people in the Superstudio collages with mobile phones…

SJ: Of course, those things were a dream then but now they are everyday reality. The potential to rethink urban possibilities is huge.

TD: Talking about science fiction, I am interested in your writing and its relationship to your work. Your writing is projective, it has an essence of the utopic, a take on alternate possibilities based on current culture. It seems to me that this type of writing is perhaps a form of contemporary manifesto. How do you consider your writing in terms of your architectural position?

SJ: The writing is to do with thinking through positions – design problems or possibilities. It’s related to being a designer. I don’t write as a critic. I don’t write as a journalist. I write as an architect. It’s not a traditional manifesto – it necessarily doesn’t make demands. It’s not single minded. It’s more a kind of endless quest that asks the question: what is the point of architecture? What are you supposed to do as an architect? What are you trying to achieve?

Sam Jacob’s Emojiopolis drawing prompts the question: if language shapes our thoughts, what effect might emoji have on them and our understanding of the city?

Image: Sam Jacob

Writing, compared to building is faster, much more personal. For me, writing is related to ideas about practice, which means I don’t compete with critics or journalists. I hate having to have an opinion about someone else’s work. My worst writing commission is to go and review a building. I‘m not interested in that. I am interested in trying to understand how architecture performs in the world. I’m not interested in writing about whether architecture is good or bad. For me, that is an irrelevant question. It’s not about judgement. That’s for other people to make. That’s the critic’s job. My job is something else and has to do with trying to understand what architecture is and what it could be.

TD: So you don’t see yourself as a critic then?

SJ: No, not in that sense. No. I think of writing as a design tool. It’s never as directly related as a traditional manifesto might be to a building that is the delivery of that manifesto. It isn’t Corb’s five points of architecture. Writing and building are simultaneous explorations and have a lot of cross currents. We can’t write manifestos in the way that you could in 1910.

TD: In 1970 the BBC produced a documentary that looked at Alison and Peter Smithson’s Robin Hood Gardens housing project, which features in A Clockwork Jerusalem. The Smithson’s talk very candidly about the project being an experiment – their imagined utopia made real. I’m not sure that we can talk about buildings being an experiment in that way anymore.

SJ: All property development has become private. There is very little state sponsored building and even when it is, it is often investment money – it comes from pension funds, for example. And, because it is investment money, it comes with so many caveats. This means that there is always a worry about risk and therefore an adversity to experiment because experiments go wrong. What is wanted is something tried and tested.

The idea of risk and failure, which is inherent in the idea of an experiment, is anathema to the building industry. But having said that, everything is an experiment because no one really has any idea if anything is going to work – there is no science to property development whatsoever. In the middle of a project that is abundantly clear. I think that design always is an experiment but perhaps we don’t have to declare it.

TD: So where do you think the space for more radical experimentation is now?

SJ: For me, the most interesting area is to work within very real situations. As much as I like to think around problems, at least half of our work has always been about very real projects – social housing projects, schools, community facilities. These are projects that are really real. Real in the sense that they are tough – tough in context, tough in budget, tough in terms of there not being any luxury to them – there is nowhere to hide. That is the most radical place you can be now.

The era of gigantic sculptural gestures as the project of the avant garde has been played out. Who cares? Who cares if Daniel Libeskind designs another shopping centre that looks like this or another holocaust memorial that looks like that? Nobody cares – it won’t add anything to human culture. The same goes for Zaha, who I think is a much better architect than Daniel Libeskind. I think she is an amazing architect – but that’s not radical. It’s amazing but it’s not radical anymore. That era’s idea of radicality was that it would be an architecture of spectacle. It is fully played out and because it doesn’t engage directly with social or political issues, it is denuded of any possibility of advancing. It’s a very narrow idea of what architecture is and what its role is in the world.

TD: It has a singular narrative as opposed to multiple narratives.

SJ: Yes. So that is where I see the real radical nature of architecture to be – thinking about the possibilities of planning for example rather than sculpture. This is where the most interesting work happens, at the intersection between the most real and the most imaginative. If you can find a way to invest one with the other – that is a powerful proposition.

TD: You talk about Libeskind and Zaha. They are seen as ‘iconic’ architects and in your work you, obviously, also have an interest in the iconic. But there are different ways to engage with the iconic. I saw the Villa Rotunda Redux project in Venice in 2012. That exhibition is an interesting take on the importance of the iconic nature of Palladio’s Villa Rotunda and also a comment on the Villa’s “embedded-ness” in architecture culture.

SJ: I don’t think the reaction to iconicity is ordinariness – that is a type of retreat. It is important to recognise that architecture is social, it is political but it is also aesthetic, it is spatial, it is material and architecture is about the way that those things work together. So the fact that things have presence is important. But the nature of that presence is much more open. I am interested less in signature design and more in the possibilities of an aesthetic project in a particular situation, in a particular context.

TD: Or what iconic might mean rather than just being iconic.

SJ: Exactly.

TD: I’m interested in the role of drawing in your architectural practice. You post your students’ drawings on Instagram and drawing figures strongly in your own work. I was wondering firstly, how you get those drawings out of your students and secondly, how that type of drawing, which is outside of or tangential to a typical architectural drawing, plays a part in your practice.

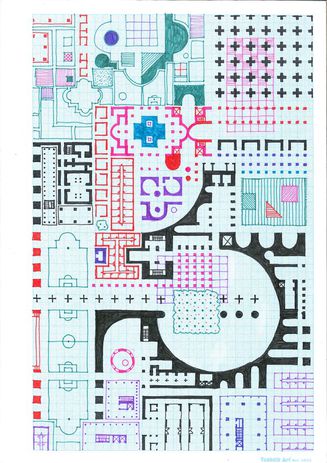

One part of a drawing series exploring the plan as an expressionistic act.

Image: Sam Jacob

SJ: My attitude to drawing comes from the fact that digital tools have changed the way that we make drawings. The thing that has been explored most of all is 3D modelling – renders. Renders assume that you model something as if it were a real thing and you render it as photographically realistic as possible. That is all very well and good and useful but it doesn’t say anything about how digital culture has changed our relationship to images.

We now relate to architecture through media. A Google image search will bring together images from all kinds of different places, at all sorts of resolutions, in relation to a particular grouping in a particular moment. Type something else in and it changes the adjacencies of those images. This is a fundamental change in how we relate to images.

The drawing project is about that – how can we reclaim drawing as an act rather than a function that comes out of an application? I was always more interested in Photoshop than rendering. Of course in the process you render things to get them into Photoshop, but in Photoshop you are actually intervening in the image itself. You are actually pulling apart pixels and layering and smoothing them out. It adds a new level to the possibilities of collage. In collage you get a bringing together of different things from different places but you still have the join, whereas in the world of Photoshop it becomes seamless. And a seamless collage is a very different kind of thing.

So with the students we encourage them to find ways of making images that draw on multiple sources. Ways of making images that draw on the histories of representation – architectural or not – that draw on the idea that you can play with authorship. In parts of the images you are curating them as much as you are drawing them. It’s a way of thinking as much as an act. It’s not just about hand-eye coordination; it’s about the coordination of your cultural knowledge. It is also a totally aesthetic project – how does aesthetics relate to content?

TD: There is an interesting level of authorship at work in that. If the 3D render spits everything out looking “real” then everything simply looks “real”. Where is the authorship that you lay over that? Where do you take control of your own project and the communication of your own ideas in representation?

SJ: The fact is it isn’t real. Photographs are not real. Perspective is not real. These are just forms of describing the world which have their own conventions. Perspective is a drawing system – it’s not how you see the world. There were other competing drawing systems at the time that didn’t win out. It’s like VHS and Betamax. Architecture is representation even when it’s real.