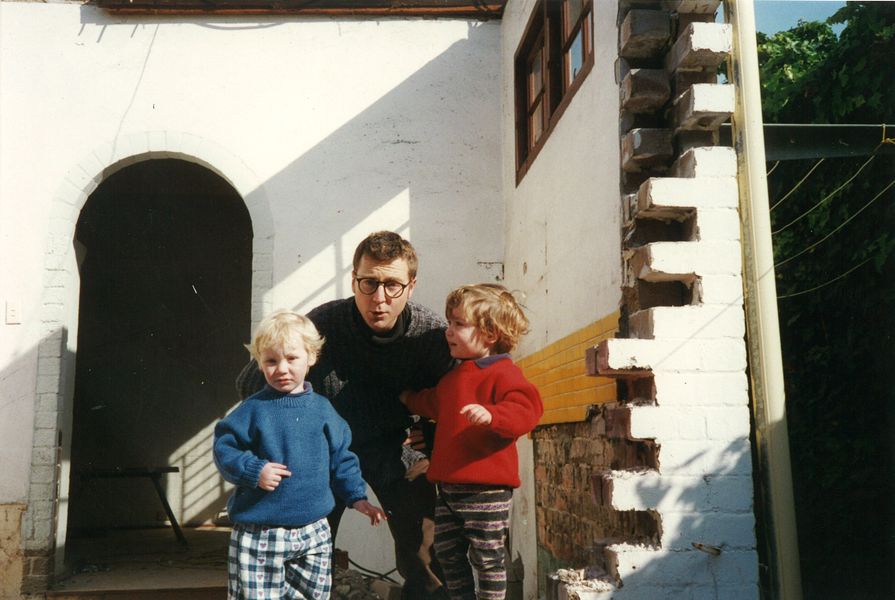

Work and life partners: Annabel Lahz (left) and Andrew Nimmo (1997) – Lahznimmo Architects.

Image: Brett Boardman

For most two-income partnerships, having children is something of a short-term financial disaster. Not only do you have the added costs of an extra mouth – or, in our case, two – to feed, clothe and care for, you also lose one of your incomes. To begin with, it will invariably be the mother’s, though it can easily swap to the father if the decision is made to continue with one parent providing full-time care at home, although it rarely does.

Strangely, this fiscal blow can open up new possibilities, especially if you are thinking of starting your own practice. Deciding to give up a perfectly good and reliably paid job to start up your own practice is not easy, particularly if you do not actually have any clients. Starting your own practice can be something of a stop-start affair. For most it is a gradual process that involves taking whatever projects you can get your hands on.

It seems a long time ago, (our children now being 21) that one year after the birth of our twin boys, Annabel and I agreed that we would swap childcare responsibilities for the first year or so. Annabel went back to work at Lawrence Nield and Partners, (now BVN Donovan Hill), and I resigned from Tonkin Zulaikha Harford, (now Tonkin Zulaikha Greer). We managed to get the twins into child care for three days a week and I looked after them for the remainder. While they were at child care, I would work on any private work that we had. We had the usual mix of low-budget terrace house additions and occasionally I would do contract work for other offices that had short-term rushes of work. There was no expectation that the practice would actually make any money to begin with. All it had to do was cover the costs, which, while working out of home, were minimal. The biggest single cost was child care. This was not always covered, but there was enough of a contribution to make it stack up – just.

This is what I mean when I say having children can open up possibilities. Having already accepted the loss of one income, there was no great risk involved in trying to start a practice provided it was not an added financial burden. There was still one reliable income. Without the pressure of having to make a certain income from the practice, we could concentrate on getting the work right and trying to build a portfolio of decent work.

Annabel continued to work at Lawrence Nield and Partners until we believed that we had enough work for both of us, which took about two years. Since then we have shared the responsibility of family and work fairly evenly. One of the great advantages of being self-employed is that flexibility is a given. You are answerable only to yourself and can take time off for family duties whenever you need to; although the flip side to this can mean catching up on work at night and on weekends.

Flexibility for family duties is expected in the work place now, but that was not the case twenty-five years ago when we worked for others. We have tried to carry this family flexibility into the practice as it has grown. Our three associate directors all have young families and our office has been recalibrating and trying to accommodate each of their particular needs. This can be a balancing act, as larger projects are very time demanding and cannot always wait for responses.

Given changing attitudes and the general push for more equality between men and women, both in the workplace and at home, I am always surprised at the strength of traditional roles within relationships, even when both people have similar training and experience. In most cases there still appears to be a clear leaning towards the career of the man’s over the woman’s. Why is that? I do not believe that this is just because opportunities favour men over women, because in many cases they do not. In our case Annabel was actually drawing a higher salary than me at the time we switched childcare responsibilities. Rather there seems to be a ‘decision’ that the couple arrives at, either assumed or agreed, that is independent of career opportunities.

In the continuing debate over gender politics, where women are unacceptably under-represented in leadership roles, couples need to take some responsibility for the decisions that they make together early in their careers.

This article updates an op-ed originally published in Architecture Bulletin – the journal of the Australian Institute of Architects NSW Chapter.