Albert K. Lim

Soi 53 Apartment, Sukhumvit, Bangkok, 2002–2004. Image: John Linkins

Jury Citation

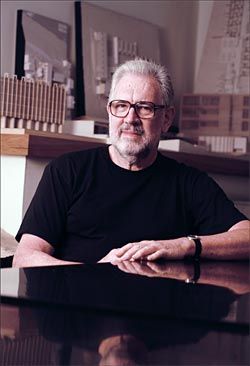

In awarding the 2006 Gold Medal to Kerry Hill, the RAIA celebrates the work of an exemplary architect who has consistently delivered the very highest quality architecture. Kerry’s uncompromising search for, and commitment to, his own architectural language (an abstract modernism overlaid with powerful yet superbly sensitive local cultural references), his faultless and inspiring material selection on each project, and the graphic and spatial quality of his planning are to be applauded.

Over the past 37 years, Kerry has distinguished himself as an architect of exceptional sensibility and expertise – encouraging a progressive and enquiring regionally sensitive approach to the design and construction of buildings across the Asia-Pacific region.

Kerry’s resort hotels are some of his most recognized and awarded work.

He is known internationally for developing an Asian resort architecture that is both climate- and site-specific, drawing on indigenous forms of tropical building to produce high quality hotels and resorts across the region in extraordinarily exotic locations. These projects represent some of the most architecturally ambitious and resolved hotel work to be found in South-East Asia, work which robustly resists the developing universalism of the theme park found in many other resorts. Celebrated examples include The Datai hotel in Langkawi, Malaysia, winner of the prestigious international Aga Khan Award for Architecture in 2001, and The Lalu hotel at Sun Moon Lake in Taiwan.

The past ten years have been a defining period for Kerry, marked by inspirational public and commercial projects such as the mixed-use Genesis Building in Singapore, the Singapore Cricket Association’s new pavilion, and the Entrance Plaza to the Singapore Zoological Gardens. Lauded private projects include beautiful residences in Australia and Asia, among which are the Ogilvie House at Sunshine Beach, joint winner of the 2003 RAIA Robin Boyd Award for Residential Buildings, and the Ooi House at Margaret River in Western Australia, recipient of a RAIA National Commendation for Residential Buildings in 1998.

As an architect whose work has made a significant contribution to the quality of the built environment across the world, and in particular in Asia, Kerry Hill is a fitting recipient of the 2006 RAIA Gold Medal.

RAIA Gold Medal jury 2006: RAIA National President Bob Nation, RAIA Immediate past president Warren Kerr, RAIA 2005 Gold Medallist James Birrell, Annabelle Pegrum, and Ian McDougall.

KERRY HILL, ARCHITECT

“I’m an architect like a dog is a dog.” Kerry Hill offered this observation on his lot in life during a recent ABC Asia Pacific Focus television programme. Hill was introduced as “the Australian architect behind some of Asia’s most innovative buildings,” and as an architect who “has specialized in adapting traditional Asian design to his decidedly modernist buildings.”%br% As director of the Singapore-based practice Kerry Hill Architects, Hill has received an impressive number of distinguished design awards within the region, including the inaugural Kenneth F. Brown Asia Pacific Culture and Architecture Design Award in 1995 and the 2001 Aga Khan Award for Architecture. He has also won the RAIA International Award three times and was joint winner in 2003 of the RAIA Robin Boyd Award for Residential Buildings.

Hill, an erstwhile Aussie Rules footballer and high jumper, is a fortunate man in that he found his calling in architecture early on and has never looked back. Since graduating from the University of Western Australia in 1968 his career in architecture has grown on an ever-steeper upward curve and his architecture has evolved into a highly refined species of pure breed.

After completing his degree, Kerry Hill’s first architectural position was with Howlett and Bailey, architects of one of the finest Modernist buildings in Perth, Council House. He worked with them on the new Perth Concert Hall and acknowledges Jeffrey Howlett as an important mentor.

In 1971 Hill took up a position in Hong Kong with Palmer and Turner, and his first project with that firm was as resident site architect in Bali for the Bali Hyatt hotel. What was originally intended to be a short working stint in Asia to help replenish depleted finances has now extended to 35 years.

In Bali, Hill found himself in a small community of Australian expatriates that included the more senior fellow architect Peter Muller and the painter Donald Friend, old Asia hands. This period was important in shaping an attitude to living and working in Asia, to responding to the differences between the known culture of Australia and the mysteries of Asia. For Hill and his young family this experience became a point of departure, a watershed in their lives.

Hill began his own practice in 1979 with the promise of a hotel commission in Bali, which never eventuated. As it transpired, the first built project of the practice was also a hotel, the first of a series that was built and numerous others that were not. The firm established its early reputation with these elegant hotels in the most exotic of locations. Hill recognized that he could build a large and successful practice around this work, but baulked at doing so for fear of being stamped as a “hotel architect” and thereby restricting opportunities to explore the architectural challenges of other building types. As a result, he has limited the size of the practice and been selective in the commissions he has accepted. He has, nevertheless, maintained an enduring and mutually rewarding working relationship with Adrian Zecha, the innovative director of Aman Resorts, who has acted as client-patron and as a creative partner in the evolution of the distinctive qualities of the Aman hotels designed by Hill. These qualities have been recognized by other hotel chains, but few have succeeded in seducing Hill to design for them.

For a period, individual houses, small distillations of the hotels, became a parallel focus for the practice. The Genesis Building, a mixed commercial and residential development in Singapore, enabled the beginnings of a more direct engagement with the city. More recently, and satisfyingly for Hill, the practice has been awarded commissions for public buildings.

Two international competitions were won within months of each other: the master plan and initial key buildings for the University of New South Wales campus to be established in Singapore, and Centrestage, the new performing arts venue for Perth.

Hill’s work is rigorously ordered, with plan resolution performing a central role. He values the development of a simple but disciplined plan early in the design process, allowing the focus then to move on to other aspects. In this strategy Hill responds to lessons learnt from Louis Kahn, with his focus on the discipline of planning and his capacity to develop an all-encompassing spatial order through this. Hill also admires Kahn’s ability to manipulate materials and light, to link the modern with the archaic, and to distil complex building programmes into strong, simple forms.

Kahn is the most constant and pervasive influence for Hill, but others are also willingly acknowledged: Le Corbusier for the strength of his original ideas and fidelity to those ideas; Frank Lloyd Wright for his planning with the focus on clearly defined hierarchical axes and the layered, overlapping massing. All three architects also share with Hill a willingness to allow their work to be enriched by understanding and embracing the architectural traditions of the East. Hill’s early work was influenced by his friendship with Geoffrey Bawa, by Bawa’s inventive responses to the local Sri Lankan setting through his modern buildings and by his capacity to surprise. Mies van der Rohe’s abstracted plans and his relentless pursuit of a singular idea remain a point of reference while, among current practitioners, Hill has a high regard for Herzog and de Meuron’s sustained and intense creativity. The traditional architecture of Japan, where Hill also has projects, is a point of reference for its capacity to generate a sense of wellbeing through its clarity and calm. In Australia, Hill acknowledges not only the work of Jeffrey Howlett, but also that of Guilford Bell. Glenn Murcutt’s architecture provides for Hill a model of discipline and approach to climate.

Hill has reaped numerous awards, has won a number of competitions and is the subject of regular invitations for speaking engagements, and his firm’s work has appeared in many architectural journals and books. However, it’s perhaps a measure of the presence of architecture on the world’s radar that, when the words “Kerry Hill” are entered into Google, we learn more about the Kerry Hill breed of sheep, originating from Powys on the English/Welsh borders, than we do about Kerry Hill the architect.

It has to be admitted that there are some parallels.

The Kerry Hill breed, we are advised, is well balanced, sturdy, with ears set high and free from wool. They are handsome sheep, good on their feet and good in their teeth. For Kerry Hill, architect, we could add patrician, authoritative, generous and utterly committed to the discipline. This commitment helps drive the practice and sustain a mentoring role that he has performed for many past and current employees. There is both tacit and open acknowledgment among Singaporean architects of the importance of Hill’s presence in that city in assisting with the development of its local architectural culture.

In support of this, what we do find on Google about Kerry Hill the architect is that he is better known and more widely celebrated in Asia than in Australia. This well-deserved award will help focus the attention of Australians on the work of Kerry Hill Architects.

Geoffrey London is professor of architecture at the University of Western Australia and the WA State Government Architect.

BEYOND GEOGRAPHY – THE ARCHITECTURE OF KERRY HILL

Ogilvie House, Sunshine Beach, Queensland, 1999–2002. Image: Reiner Blunk

The work of Australian architects is not limited by geography and this year’s awarding of the RAIA Gold Medal to Kerry Hill is an important recognition of that fact. His is a truly significant international practice. Unlike previous medallists who have built in overseas locations from practices based in Australia, Hill is part of a substantial contingent of expatriate Australian-trained architects and academics, who have practised or been practising outside this country, often for decades. They have been ambassadors for Australian practice and, more often than not, they have earned global stature independent of citizenship. Thus, Kerry Hill rightly sits within the stellar ranks of architects like Raymond McGrath, John Andrews, Peter Wilson, Hank Koning and Julie Eizenberg, and academics like Bill Mitchell and Peter Rowe, all expatriate Australians who have made significant contributions to the international world of architecture.

For Kerry Hill, international acclaim has rested mostly with the design of a series of serenely planned and detailed resorts in paradisiacal tropical locations. Hotels such as The Datai, Langkawi, Malaysia (1990–1994); The Chedi, Bandung, Indonesia (1992–1994); and Amanusa, Nusa Dua (1990–1992) and The Serai, Manggis (1992–1994), both in Bali, are acknowledged as important (and theoretically controversial) bulwarks of place-making and craft tradition in an increasingly competitive culture of global capital. With the rise of regionalism in architecture discourse in the 1980s, Hill’s architecture represented a poignant moment in South-East Asia, and was seen as a logical inheritance to the mantle of Geoffrey Bawa and Peter Muller in Sri Lanka and Bali, respectively.

However, the difference between their work and that of Hill lies in Hill’s tectonic and material rigour in terms of form and type, and his rethinking of tropical urbanity and concepts of urban agglomeration. These urban ideas suggest broader applications for Hill’s work, moving it beyond images of place that suggest hegemonic cliché and nostalgia or closure to questions of form. Hill’s more recent hotel projects for Kolkata, Dubai, Croatia and Taiwan indicate a further decisive move – a move away from recasting recognizable typologies towards a higher level of abstraction and refinement of detail. This strategy reinforces the design strengths that have long underpinned Hill’s architecture: a rigorously orchestrated sequence of arrival, reception and spatial release, based around themes of axis, court and framed view.

This same careful rationalism, this recasting of orthodox architectural forms and devices, also marks Kerry Hill’s individual contribution to Australian architecture. Hill can be placed within a strong and ongoing tradition of place-making in Australian architecture – one that includes Glenn Murcutt, Troppo, Richard Leplastrier, Brit Andresen and Peter O’Gorman. However, his architecture suggests typological reinvention and sometimes its inversion, always within the context of an ongoing project of modernity. This idea is little discussed within the context of Australian architectural history, but it properly includes the work of Howlett and Bailey, the spatial platforms and outdoor rooms of the houses of McGlashan & Everist, the studied informality of Neil Clerehan’s underplayed modern villas, the typological and structural systems of Joyce Nankivell, the monumental but never neutral urbanity of Yuncken Freeman, and the improbable (but often realized) planar compositions of Neville Gruzman. This is not the pervasive and fashionable currency of an uncritical and superficial modernism. Instead this work exhibits an unwavering commitment to rethinking models from a typically modernist standpoint – from first principles in plan, form and structure but always mindful of light, tactility and context. Hill’s Ogilvie House at Sunshine Beach, Queensland (2003), for example, is unlike any other contemporary house in subtropical Queensland. It doesn’t adopt the usual local palette of corrugated iron, fly-away roof and excited appendages of shading devices. Its pedigree lies more with Hill’s recent shedding of iconic vernacular moments and his emphasis on the abstract, fundamental components of controlled spatial sequence, the casting of deep shade through emphatic horizontal roofs and timber screens at the very edges of his forms, and the continuous deployment of the courtyard as a self-shading mechanism. It is this latter space – the courtyard – for which Hill deserves particular celebration. Hill uses the courtyard for psychological containment, for borrowing shade from walls rather than obvious roofs, for spatial extension to frame views or vertical connection with the sky, for retreat from the relative chaos of the city without, for the courtyard’s ability to cross-ventilate between spaces, and for the opportunity to use water or plants to provide visual relief and contemplation. This deployment of the courtyard as a key element of tropical design offers an important lesson for Australian architects in its potential application to the Australian context across a range of climatic and urban contexts.

If there is a measure of orthodoxy present in the work of Kerry Hill, it is in the conscious realization of local capabilities in terms of construction practice, climate and material longevity, and the specific circumstances of urban and landscape location. Hill’s work also falls within that category of Australian architects committed to a modern reading of urban morphology, where the historic forms of the city are uncovered and not imitated but abstracted and given fresh form. In Australia, Hill’s work aligns with the formal but considered sobriety of Guilford Bell, Espie Dods, Alex Tzannes and Alex Popov. In this work questions of street, pathway and spatial sequence as a considered orchestration of experience are critical to understanding the city, and to the potential for each building to encapsulate the city in miniature. This is an architecture of walls, framed views and, in Hill’s words, “the intrinsic value of one material paying respect to another”. Hill’s recent commission for Centrestage, the new performing arts venue in his home city of Perth, offers a unique opportunity for these ideas to be explored on a grander public scale than the secure bucolic settings of his Australian residential projects. It is a worthy commission that coincides with the receipt of his profession’s most prestigious award, and is the logical next phase in the series of distinguished urban projects from his office that now dot the eastern half of the globe.

I first met Kerry Hill in his office, a converted Chinese shophouse in Singapore. In person, Hill is an unassuming figure, almost shy, a man of very few, always well-chosen words. He has been a conscientious mentor to some of the region’s most vital young practitioners, yet he can be simultaneously aloof when such a condition allows freedom. Like his personal presence, his architecture is an elegant backdrop for the largeness and relevance of place.

Dr Philip Goad is professor of architecture, building and planning at the University of Melbourne.

RUMINATIONS ON A LIFE IN ARCHITECTURE

Genesis building, Singapore, 1994–1997. Image: Jon Linkins

I have been asked to reflect on the influence of Kerry Hill in South-East Asian architecture.

I would reply, it is an influence that extends beyond South-East Asian architecture; it is an influence on architecture per se.

Influence? The dictionary defines this as follows: the effect of something on a person, thing, or event; the power that somebody has to affect other people’s thinking or actions by means of argument, example, or force of personality; somebody or something able to affect the course of events or somebody’s thinking or action.

If we consider the effect of Kerry Hill on persons, events and things related to architecture, we must say that he has a profound influence.

A school has evolved from Kerry Hill’s practice of architecture, just as schools have developed from the work of Rem Koolhaas of OMA, Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron of Herzog & de Meuron, and Toyo Ito of Toyo Ito & Associates. Many former members of Kerry Hill Architects have become prominent and important practitioners – they have also become influential. They have become people whom people watch. They move and shift the way architecture is being done; they move how architecture is being seen. They achieve this through their works, their writings, their presence.

They include WOHA, both Wong Mun Summ and Richard Hassell; Cheong Yew Kuan; Ernesto Bedmar of Bedmar and Shi; Richard Ho. All have at one time worked or collaborated with Kerry Hill.

Influence? It could mean being watched for explorations, the simple architectural moves that determine waves of actions and strategies in architecture. For example, Kerry Hill’s screen on the Genesis building in Singapore (1994–1997) created an explosion of work on the possibilities of wooden screens around South-East Asia. This gesture of a wooden screen on the facade of a building catapulted a simple device that responds to wind, breeze and sun, so necessary in the tropics, into everyone’s consciousness.

Influence? I could mention Kerry Hill’s influence on the exploration of space using a modern idiom; on probing the vocabulary of architecture; on ways of using the physicality of architecture to create a space, to evoke an atmosphere. Or the exploration of details and material combinations, the handling of light and shadow, the passage of a breeze. I could mention the exploration of modern architecture, the pristine beauty of forms and of correct proportions. Or the investigation of making an architecture for a particular context, the challenge of universal ideas, and the particular emergence of forms. Or the response to climate, to clients’ desires, to the demands of regulations and guidelines.

Above all, Kerry Hill has a profound influence in showing how one can explore patiently, with perseverance, and in very subtle and simple ways.

His exploration is pursued with vigour and resoluteness. It is also an excellent example in the exercise of restraint – of knowing when enough is enough.

The resort and hotel projects go beyond tropical formal architectural qualities towards both questioning and proposing the ideal experience that might unfold in such places. They also explore how an architecture which makes spaces through incessant repetition and iteration might pursue a search for that space that feels just right.

What of the influence on expanding the horizon of exploration towards the future? Kerry Hill demonstrates how the pursuit of ideas can expand from one typology and scale to another. The shift from hotels and resorts to academic environments and an arts centre is valuable for showing how the strength of conscious exploration of architecture can promote renewal and regeneration. The effort to break from a mould, to pursue possibilities of how spaces of encounter can be orchestrated and crafted, is shown in Kerry Hill’s recent competition-winning schemes for the UNSW Asia Campus and Centrestage.

And the influence on how one extends or expands a legacy? We might learn from Hill’s interaction with Geoffrey Bawa, his conversations about an Asian Modern and the issue of tropicality; his conversations with predecessors like Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe and Louis Kahn.

These show how one might move towards creating one’s own language and expression, through the inspiration and challenging of a predecessor. There is also a consciousness of roots and beginnings in architecture – Hill’s fond reminiscences of mentors like Duncan Richards and Jeffrey Howlett; his humorous recollections of personal traits that influence architecture and an analytical assessment of oeuvres and working methods. Kerry Hill has extended our consciousness of those who built the path that we tread and will explore. He shows us how we can conceive a dialogue with the giants of architecture while also conversing with colleagues who are in pursuit of making architecture.

Kerry Hill’s oeuvre of the past twenty years reveals a patient pursuit of “Architecture”. In many ways, architecture can be very autobiographical.

We see Kerry Hill’s architecture as tranquil, quiet, elegant and bold. Somehow these words also express the character of Kerry Hill as a person: a character that is tough, persevering, patient, inquisitive, with a sense of humour and, most of all, serene. Perhaps Kerry Hill’s influence is, above all, in his example of how an architect can live a life in architecture, life as architecture, architecture as life?

Kerry Hill shows us in his calm way how architecture is life, how life is architecture.

Erwin J. S. Viray, PHD, is assistant professor at the National University of Singapore and co-editor of A+U (Architecture and Urbanism) in Tokyo.