Throughout its thirty-year history, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy has been a touchstone of controversy. Most recently, an accidental fire at the site has become the catalyst for a new attempt to remove the embassy. Indeed, only weeks earlier, the Canberra Times reported that Reconciliation Place’s dedication also marked “the first step towards” the embassy’s replacement.

Such controversies are a compelling reminder that the Aboriginal Tent Embassy remains one of the most politically and symbolically charged sites in the national capital. Although not the work of an architect or landscape architect, the embassy and its surrounds constitute an important, designed, landscape.

Arising from a growing sense of alienation – a belief that Aboriginal people had, effectively, been made foreigners in their own land – the embassy was launched on 26 January 1972 (Australia/Invasion Day). At first literally a tent and later a shed, the embassy is located on the Griffins’ Land Axis, near the front steps of what was then Parliament House (now “Old”). The use of the site as a political forum was not without precedent – along with the opening of (Old) Parliament House, 1927 saw the site’s first Aboriginal protest – and earlier Aboriginal occupation of the site was centuries old.

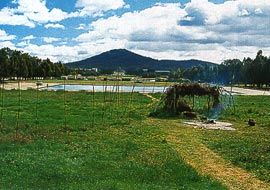

Today, no longer contained in a single structure, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy has activated its wider landscape as a dynamic medium of protest. Expanding out into the surrounds, a composition of gunyahs or humpies – derived from a “fire dreaming” narrative – was constructed in the late 1990s. Arrayed about a perpetual sacred fire, each of these brush shelters has its own symbolic association. The group’s set piece humpy is centrally positioned on axis, immediately behind the fire and a screen of spears (each representing a choice for alternative futures). Facing and confronting (Old) Parliament House, this humpy is a symbolic vessel, containing “the Law and the real government, the old government of this land, the true Sovereign authority which has never been ceded”. To rest within this shelter, amidst the wood smoke, and contemplate the view up the axis to (Old) Parliament House and its new counterpart beyond, is a primal, ethereal experience. But this fire is not the first on the site either; in 1993 the ashes of poet and original protester Kevin Gilbert were scattered into a nearby “Fire for Justice”.

The “Law” humpy was originally one of a pair; the second is now gone (possibly through action by an errant lawn mower).

Juxtaposed behind the first, the lost humpy was oriented in the opposite direction toward Mount Ainslie. This shelter referenced peace and the land, where the Aboriginal people “have come from and the only peaceful way forward for this country”.

With the loss of this humpy (and others), the installation’s symbolic content was diminished. Yet its potency lingers. More recently, the installation has taken on a global, pan-tribal dimension as expressed in the collection of new flags which now join the Aboriginal flag (the design of which was conceived on site in 1972) at the embassy.

These cultural banners offer an indigenous counterpoint to the “official” national flags displayed at Lake Burley Griffin’s edge.

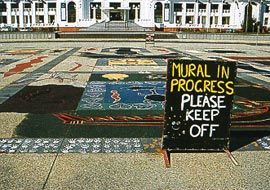

About the time the humpies appeared, (Old) Parliament House’s forecourt terrace became a mural canvas. A postwar modernist addition, the terrace is a concrete expanse, visually relieved by a constrasting grid of pavers set within. Now an emulsion of totemic animals covers the surface.

Beneath the wings of an eagle, the “carrier of law”, fauna gather at (Old) Parliament House, en route to the sacred Kurrajong (Capital) Hill above. The contrast between the painting’s forms, shifting within the grid of pavers, and the almost classical ambience of the terrace and nearby reflecting pool and fountains (and the building itself) could not be greater.

The central mural and humpy installation is contained laterally by the tree plantations that accentuate the Land Axis corridor. In contrast to the geometry and exoticism typical of much of this urban forest, clandestine plantings of eucalypts and other Australian trees meander throughout the embassy precinct. A monolithic statue of King Edward, once heroically positioned on axis, sits to the side of one of the plantations (the statue’s shift was an act not without symbolic resonance). Within the metaphorical gaze of this imperial presence, the plantations have been appropriated as camping grounds. This occupation is reflected by the proliferation of tents, caravans and automobiles beneath the tree canopy. This assemblage is, in itself, provocative. Camping in this otherwise ceremonial parkland, along with fires, is illegal.

The embassy’s landscape has evolved opportunistically. Several years ago, for instance, a dispute between embassy occupants and a landscape maintenance crew led to the precinct’s grass going unshorn for some weeks. The pristine turf quickly deteriorated to become a tangle of grasses. Engulfing new eucalypt plantings, the rank growth took on the appearance of an emergent urban ecosystem. Occupants soon cut a network of sinuous pathways through the high grass to link embassy, humpies and fire. When compared to the wider turf surrounds, the length of a blade of grass could now be read as a political statement. Later, however, the grass was returned to manicured conformity.

The Aboriginal Tent Embassy challenges conventional aesthetic sensibilities. The compound is far from “tidy”. In unsettling contrast to its meticulously groomed environs, an aura of dilapidation pervades the site. This circumstance is not without a degree of calculation; the embassy’s precinct is said to mirror the living conditions of many Aboriginal people.

As a habited crucible of cultural dialogue and protest, of Gilbert’s ashes and memories, the ground itself is layered in meaning. Perhaps owing to this, and despite the eventual removal of Parliament to new Parliament House, the Tent Embassy endures at its present site. As the national capital’s most politically animated site, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy resonates with the Griffins’ endeavour to elevate designed landscape above the passive role of mere setting. The very name “Canberra” is said to be derived from an Aboriginal dialect and to mean “meeting place”. The Tent Embassy most certainly continues to fulfil this vital role. Surely this is yet another reason to value the presence of this potent designed landscape.

Christopher Vernon is a senior lecturer in landscape architecture at the University of Western Australia