LANDSCAPE

The end of the loop, looking towards the Gallery of First Australians. Howard Raggatt can be seen lower right.

A year ago the National Museum of Australia (NMA) and the Garden of Australian Dreams splashed down on the placid waters of Lake Burley Griffin. Ripples from that splash have been felt across Australia and beyond. Twelve months on, discussions about the garden and the siting of the complex in the broader landscape of the national capital continue, making it the most talked about piece of landscape architecture in Australia’s history.

This vigorous and sustained debate has disturbed the subdued discourse that characterises landscape architecture in Australia, even generating the occasional shrill note. (James Weirick called it “a vortex of madness so horrible it is wonderful”.) For a profession with a restrained design palette and a poorly developed critical culture, such debate is unusual… and welcome. Landscape work here characteristically integrates rather than stands out. The landscape of the NMA, particularly the Garden of Australian Dreams (or, as some say, nightmares), challenges this tradition, and it does so fearlessly.

The Garden of Australian Dreams not only attracts professional debate, it also appears to be well loved and well used - by children who seem absolutely familiar with its particular form of hyperreality (if not the metaphoric messages embedded in its elements and composition) and by adults who respond to its sensory power and ponder its meaning. The garden presents its very fabric and form as an exhibit; an embodiment of the way Australians think about their land and landscape. Intelligible to Australians who recognise many of its signs from sources as diverse as geography lessons, popular imagery and their own suburbs, it is unclear whether it is readable to those from elsewhere.

What is clear, is that the Garden of Australian Dreams has met one of its designers’ goals, to challenge the traditions and mores of the profession, and, just as importantly, to be seen to be doing so. It has also achieved visibility. With all the noise about the garden, however, one hears little about the more traditional design of the landscape to the lake and peninsula. This is still maturing and, because of its subtlety, remains less visible and therefore peripheral to most debate. Will both stand the test of time? ›› Thankfully, the design for the NMA complex was realised outside the Parliamentary Triangle, where more time for careful crafting and longer lasting materials would have been required. The unrealistically small budget and tight delivery schedule has resulted in flimsy structures and surfaces. The development hardly feels permanent and, irrespective of their conceptual brilliance, neither landscape nor building are likely to age with dignity. Unlike Canberra’s other cultural institutions which remain virtually unchanged for decades, the NMA is more akin to malls or fun-parks which require (and expect) repeated facelifts to maintain their appeal. Regular makeovers and reinventions of buildings and landscapes are not easily imagined in the stasis that characterises central Canberra, let alone the National Triangle. Here, however, they might be possible. One can only hope that they are carried out by the original designers to maintain the vigour and popularity of the complex. Otherwise it might lapse into pastiche or acquire the depressing tackiness of a once-flamboyant holiday resort repeatedly renovated by amateurs. The NMA’s ongoing difficulty in attracting funding along with recent adjustments to the garden in (overzealous) response to health and safety issues signal real cause for concern, however, and one suspects that the NMA and the government have not really considered such life-cycle issues in budgetary and design terms.

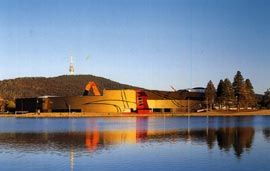

There is also the question of whether this contemporary lakeside folly will acquire the lyric qualities of the more traditional follies that decorate other iconic lakeside landscapes internationally. The retained vegetation, the set back from the lake edge, and the newly planted perimeter eucalyptus groves look set to ensure that the building will settle in, with the foreground of water, backdrop of Black Mountain and the maturing woodland frame increasing its mystery and the sense of invitation from across the lake.

The landscape of the NMA and the debate it has generated will not be forgotten quickly by the design professions and more debate is likely as it matures and is or isn’t re-invented or made over. As a landscape of layering, there will always be ways to enrich and reinterpret the complex story this landscape embodies - that of land, people and nation. The question is how will that reinterpretation happen and, if so, by whom.

Catherin Bull is Elisabeth Murdoch professor of landscape architecture at the University of Melbourne. She was on the National Capital Authority board from 1992–1997

MUSEOLOGY

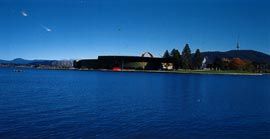

Two views of the complex in its broader landcape setting, across Lake Burley Griffin, with Black Mountain beyond.

Aerial view of the Acton Peninsula.

Looking from the lakeside amphitheatre towards the Main Hall.

Overview of the Garden of Australian Dreams, seen from the east. xxxxx The Garden of Australian Dreams, with the permanent gallery beyond. Recent alterations to the garden, in overzealous response to health and safety issues, can be seen in the foreground.

Museums have come a long way since the American artist and critic Brian O’Doherty coined the term “white cube” to describe a certain mode of modernist museum and gallery design. Such exhibition spaces were supposedly neutral, abstracted from the contingencies of everyday life in the world, and set isolated artworks and cultural artifacts aside in a quasi-sacred realm. With the NMA, the reaction against such a rarefied, transcendental notion of the museum’s role and character has perhaps come full circle - in its polychromatic formal complexity the NMA could hardly be further from a white cube museum. This is true, not only of the architecture, but at every level - from the minutiae of object selection, placement and juxtaposition, through its curatorial narratives and themes, to its projection of a troubled and troubling national identity. In this, as in other respects, the NMA can be seen as an exemplar of a new generation of social history museums, institutions which have broadened their focus from an emphasis on the past - particularly as it is made present by authentic historical artefacts - to an ever-increasing emphasis on reflecting the present and imagining the future. The institution’s stance has shifted: from a vanguard position, following behind the tumult of historical events as birds follow the plough, to an explicitly avant garde position - not simply recording, but actively participating in culture. One year after the NMA’s opening, its slightly battered, shop-worn displays attest to the level of popularity that this new museum does, indeed, enjoy.

In the NMA the fit between museum building and museum ideology is, at least at an abstract level, remarkably close. This is surely because the building design and the curatorial approach evolved together, given that there was no pre-existing national museum as such. It must also result from the aptness of the overriding allegory - Australian nationhood as many stories tangled together - which informs the museum at both its physical and intellectual levels. In the installation, however, that is in the way the exhibitions and their objects are actually fitted into the space, the relationship seems less successful. Certainly the architects have presented the exhibition designers with a challenging, unconventional museum space, but in some places there is a clear disjunction between the two. On the mezzanine in the north permanent gallery, for instance, the spatial excitement of a mezzanine - views down into other galleries below, vertical flow of sound and light - has been largely thwarted by the placement of fullheight showcases against the balustrade.

There is, however, one exhibit that seems to me emblematic of the relationship between architecture and museum apparatus. This is a small exhibition, tucked into an unobtrusive corner, which is called Building the Museum. As this title might suggest, it is a display of objects and documents relating to the design and construction of the NMA building. This foregrounding of architecture as itself a museum object has been done before - in the National Gallery, for instance, where the first object label to be seen upon entering gives the architect, media and year of the building. If in that case the building is treated as an art object, in the NMA the building is presented as a cultural artefact, one which is equally a process, a performance, and a narrative. The exhibits include battered utilitarian objects such as shovels, hardhats and site notices, juxtaposed with architectural sketches, drawings and models (including a remarkably beautiful model of the “knot” around which the museum’s Main Hall is formed), and photographic documentation of the construction process. To me, what is most interesting about this display is its hall-of-mirrors effect. It is an exhibit about a museum within the museum itself: it represents the museum’s making an exhibition of itself, literally and selfreflexively.

It is a model of the NMA’s wider museological approach, in that it proposes that a museum is not simply a collection of objects, but a collection of stories based around those objects. Artefacts no longer act as evidence of authorised history, or of some other grand scheme, nor are they specimens to complete an encyclopaedic table - objects are simply the focus for the telling of stories. Thus the museum building itself is yet another artefact on a continuum of museum objects; it presents itself to be read and deciphered, to be the site and source of narrative.

Naomi Stead is an associate lecturer in architecture at the University of Technology, Sydney

ACTON PENINSULA ALLIANCE

Looking over the mezzanine in the north permanent exhibition space. The Horizons gallery is on the upper left and the Tangled Destinies gallery below. Full-height showcases on the mezzanine work to separate these two spaces, limiting the possible spatial experiences from the mezzanine.

The Main Hall, looking towards the entrance.

The exquisite model of the “knot”, used to cast the form of the Main Hall, displayed in the Building the Museum exhibition.

Moving under the loop, towards the main entrance to the Main Hall.

Lakeside entry to the Main Hall.

Looking west from the north terrace to the end of the administration building.

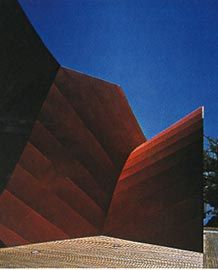

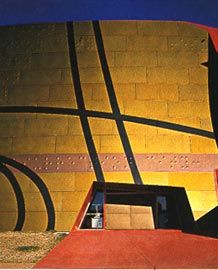

Detail of the east facade, facing Parliament House, showing the physical end of the Uluru Line.

Exiting the museum, under the looping canopy, towards the carpark. The AIATSIS building is seen in the distance

Current building industry practice is noticeably moving towards project delivery systems that are less bloody-minded than traditional hard money contracting. It has taken a long time for people to come to grips with common misunderstandings such as: unreasonable risk transfer means no more problems; the tendered price more or less equals end price; the lowest price is the best outcome. Increasingly, those in the industry are also realising that enabling and supporting systems that send honest businesses broke and create poisonous workplace relations, may not be the best use of their time or their talents.

Early attempts to address these problems, such as partnering, were worthy initiatives with attractive rhetoric, yet, at their heart, they often had the old boilerplate contract sitting in the client’s (lawyer’s) drawer. This is the critical test of whether real change is afoot - an old-style contract indicates that the rhetoric and workshops are probably window dressing.

The alliance project structure used for the NMA was transferred from infrastructure projects. The Commonwealth sponsored the idea, in the belief that it gave the highest probability of achieving their desired project outcomes. The alliance delivered. The project was on time (three and a half years) and on budget, and independent panels judged it to be a high quality project that has maintained design integrity. The NMA has also enjoyed more than double the anticipated visitor levels and has received many national and international awards, from both the profession and the industry.

So what is a project alliance? Although most things are done the same way as in a hard money contract, there are some crucial differences. The following characteristics can be used to ascertain how “new” a contracting arrangement really is and how serious the project sponsor is. All parties sign one agreement, there are no side agreements. All parties have representatives on the Alliance Leadership Team (ALT), who must be capable of binding their respective parties. All decisions must be unanimous, there are no dispute resolution procedures. All parties are assured of receiving their direct costs (salaries and out-of-pocket expenses). All parties put their normal overhead and profit (OH&P) at risk against a set of risk and reward curves, which vary above and below the benchmark of “business as usual” (BAU) OH&P. If the alliance does a better than a BAU job, as defined by the risk and reward, the parties receive a better than BAU OH&P. The reverse may also apply. The risk reward curves may differ markedly to best suit the objectives of particular projects. There must be a comprehensive, rigorous selection process, aimed at getting the right people in place. Price is never discussed until the preferred people are together.

The agreement must be constructed so that the only possible outcomes are win/win or lose/lose: if win/lose is possible, the agreement is wrong.

If this all sounds a bit brave new world, it is at first. It takes significant adjustments in attitude from all players. Does it work? With the right selection process, yes. Does it deliver good value for money, with appropriate probity and controls? Yes, according to the Australian National Audit Office, and KPMG, the Department’s auditors. Can it be improved? Definitely. The “lessons learned” workshop identified a number of issues.

Should architects promote this kind of arrangement? This is difficult. In terms of good working arrangements and great potential outcomes, it has much to offer. However it is also possible for the architect to be caught in conflicts of interest if the risk reward framework is constructed so that “pure” design decisions, while improving a design outcome, may penalise the architect (and all the alliance partners) financially. This needs to be considered carefully in any particular framework. The idea of the “pure” design decision is also a matter of spirited debate. Design does not exist in a vacuum, it is always a result of the “cultural brief” as well as of the endeavours of the design and construction team. Architecture will always reflect the values of the culture that enables it, so whatever the framework that makes the architecture possible, the result is just that: the result!

The Acton Peninsula Alliance has created many firsts - in computer technologies, construction techniques, project agreements, sub alliances and other innovations. This alone suggests the experience must be studied carefully as a possible way forward for our industry. After all, work should be fun and rewarding for everybody. Perhaps this is not a bad starting point for an arrangement between people who want to make a project?

Steve Ashton is a director of ARM Architecture

For plans and a full list of credits please see Architecture Australia 90/2, March/April 2001.

Images: Peter Bennetts

Looking across the roof of the Main Hall, towards Black Mountain.

Credits

- Project

- National Museum of Australia

- Architect

- ARM Architecture

Australia

- Project Team

- Craddock Morton, Peter Wright, David Waldren, Garry Eggleton, Philip Johns, Steve Ashton, Howard Raggatt, Ian McDougall, Robert Peck, David Waldren, Ken Bool, Alan Ball, Allan Flynn, Andrew Hayne, Antony McPhee, Catherine Evans, Chris Reddaway, David Homburg, David Murrell, David Pryor, Doug Dickson, Ivo Tanevski, Gustav Kroyherr, Jacinta Vines, Jan van Schaik, Jesse Judd, Lilliana Andjelkovic, Lorenzo Gelati, Natalie Plumstead, Neil Masterton, Nevena Bresoska, Nikolas Koulouras, Paul Dash, Paul Minifie, Peter Ryan, Poh Raggatt, Rod Newton, Sally Hieatt, Simon Sheil, Sue Adams, Sue Dove, Tim Wright, Richard Weller, Tom Sitta

- Consultants

-

Access consultant

KLCK

Acoustics Bassett Acoustics, Eric Taylor and Associates

Audiovisual consultant Canberra Professional Equipment

Building services Tyco International

Civil engineers Young Consulting Engineers

Communications engineer Diverse (Tyco)

Exhibition designer Anway and Co

Exhibition joinery fabrication Classic Resources, Designcraft, Stag Shopfitters, UTJ

Fire engineer Bassett Consulting Engineers, Ove Arup

Glazing and facade systems G James

Hydraulic engineer Young Consulting Engineers

Landscape Urban Contractors

Landscape architect Room 4.1.3

Lighting Vision Lighting

Mechanical and electrical engineers Bassett Consulting Engineers

Object install Thylacine Exhibition Preparation

Project management Lendlease

Project manager TWCA, Acton Peninsula Alliance

Quantity surveyor Slattery Australia, Donald Cant Watts Corke, Wilde and Woollard

Security and BMS Contractor Honeywell

Security engineers Honeywell

Structural engineer Ove Arup and Partners

Structural steel National Engineering

Traffic engineers Ove Arup and Partners, Hughes Trueman Canberra

- Site Details

-

Location

Lawson Crescent, Acton Peninsula,

Canberra,

ACT,

Australia

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Type Public / civic

- Client

-

Client name

Commonwealth Government of Australia