Among other things, Lori Brown is an associate professor at the University of Syracuse School of Architecture. Her book Feminist Practices: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Women in Architecture was written as a direct response to the lack of visible female architectural role models for her students and for the profession in general. Her brand of feminism is broad and inclusive. It focuses on issues of social justice and the idea that change within the structures of architectural practice will create a better profession not only for women but for all architects.

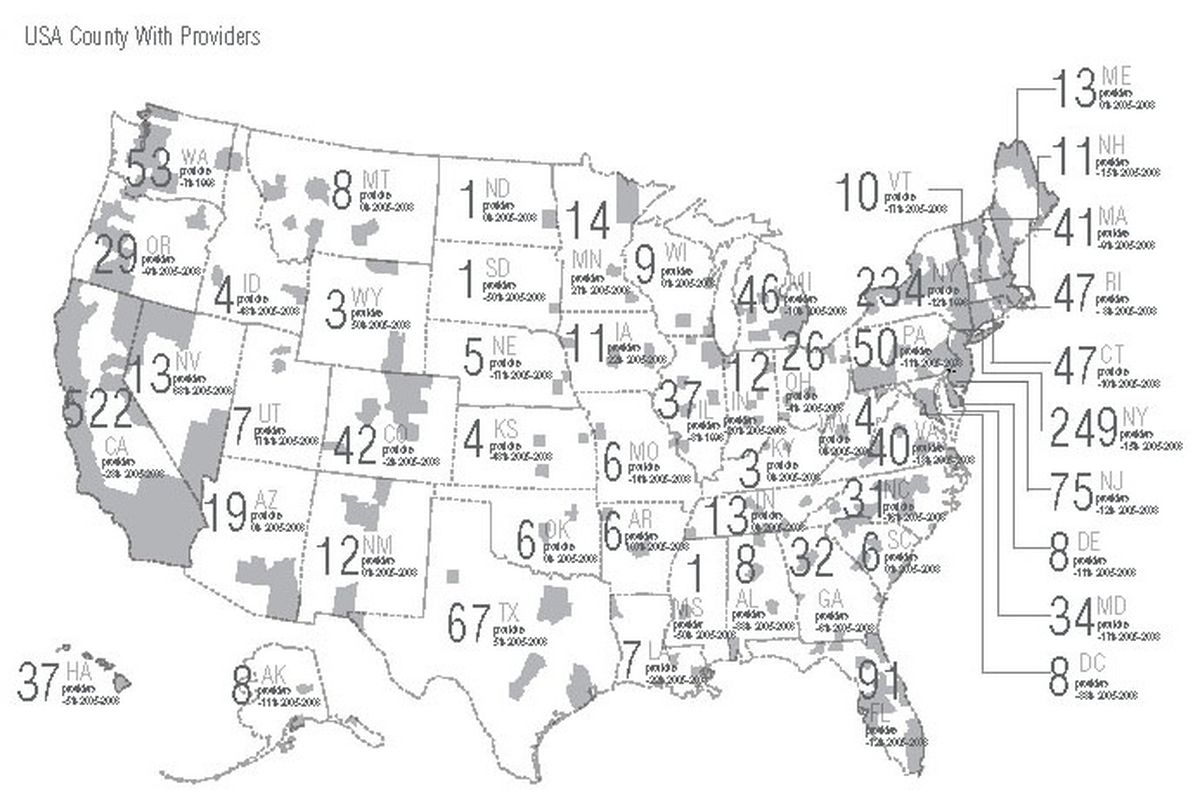

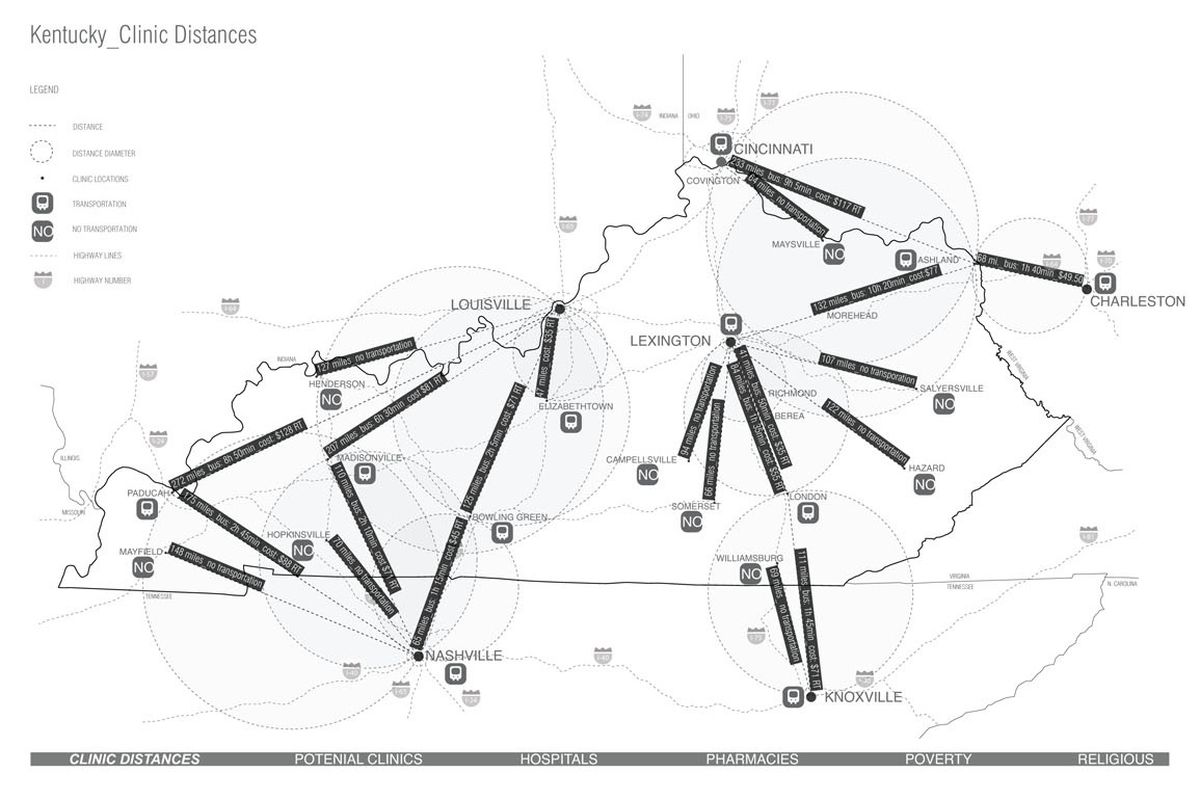

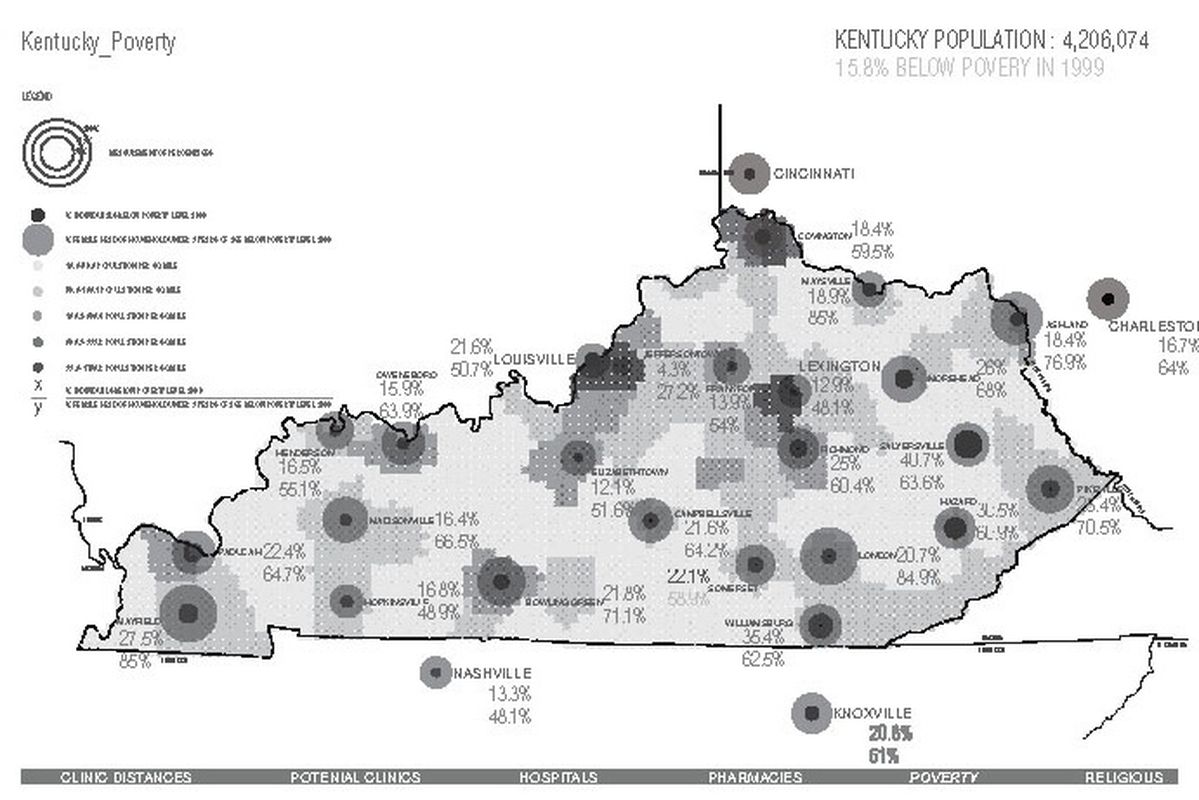

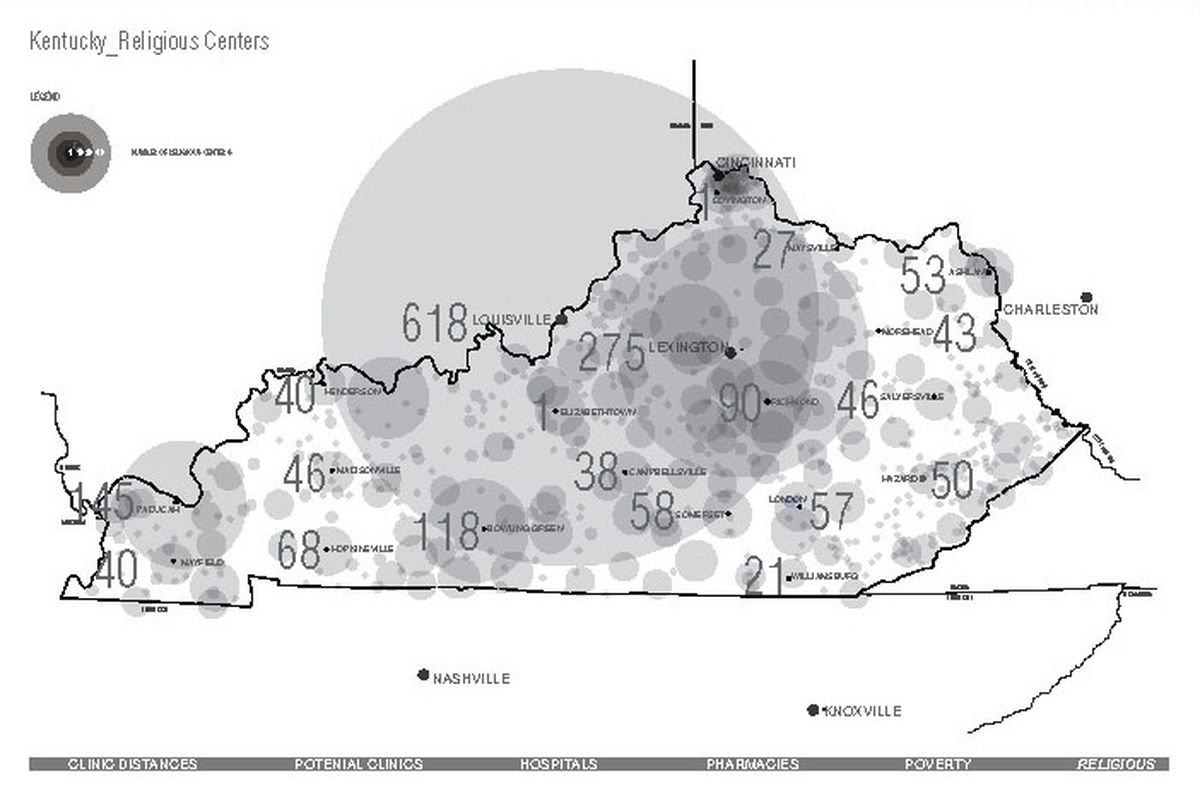

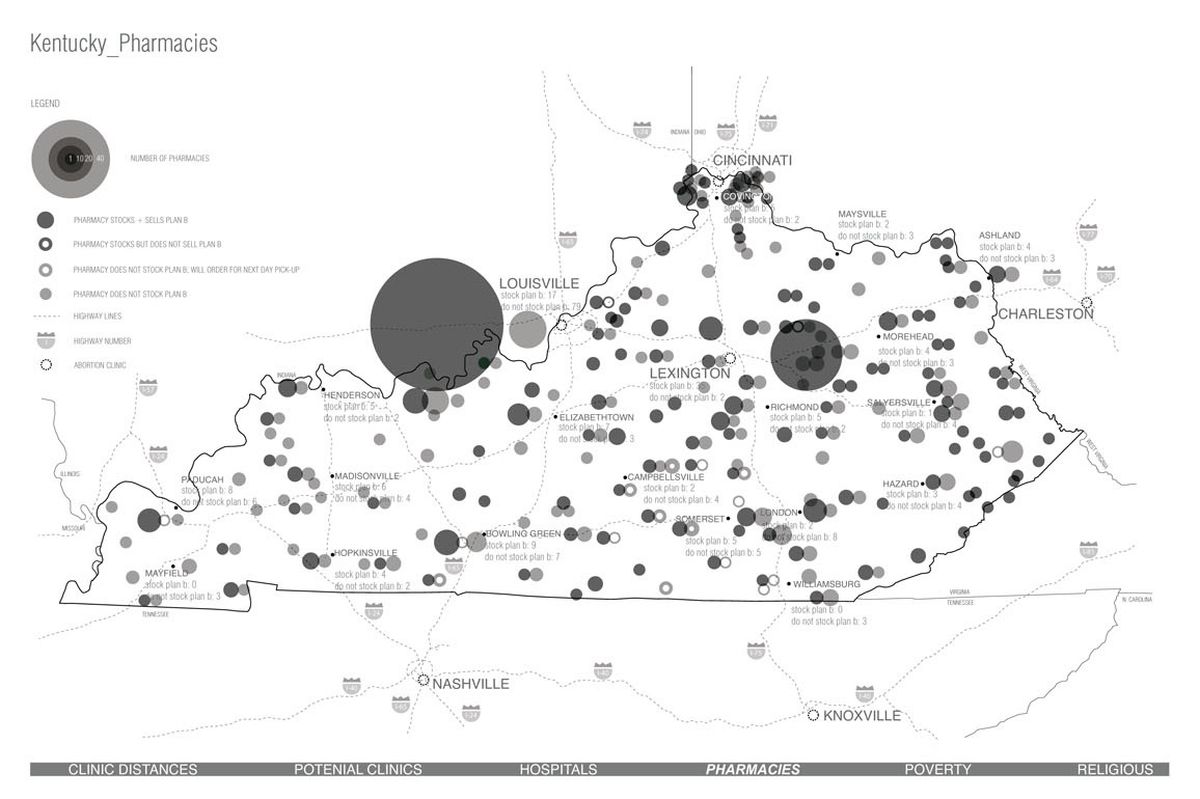

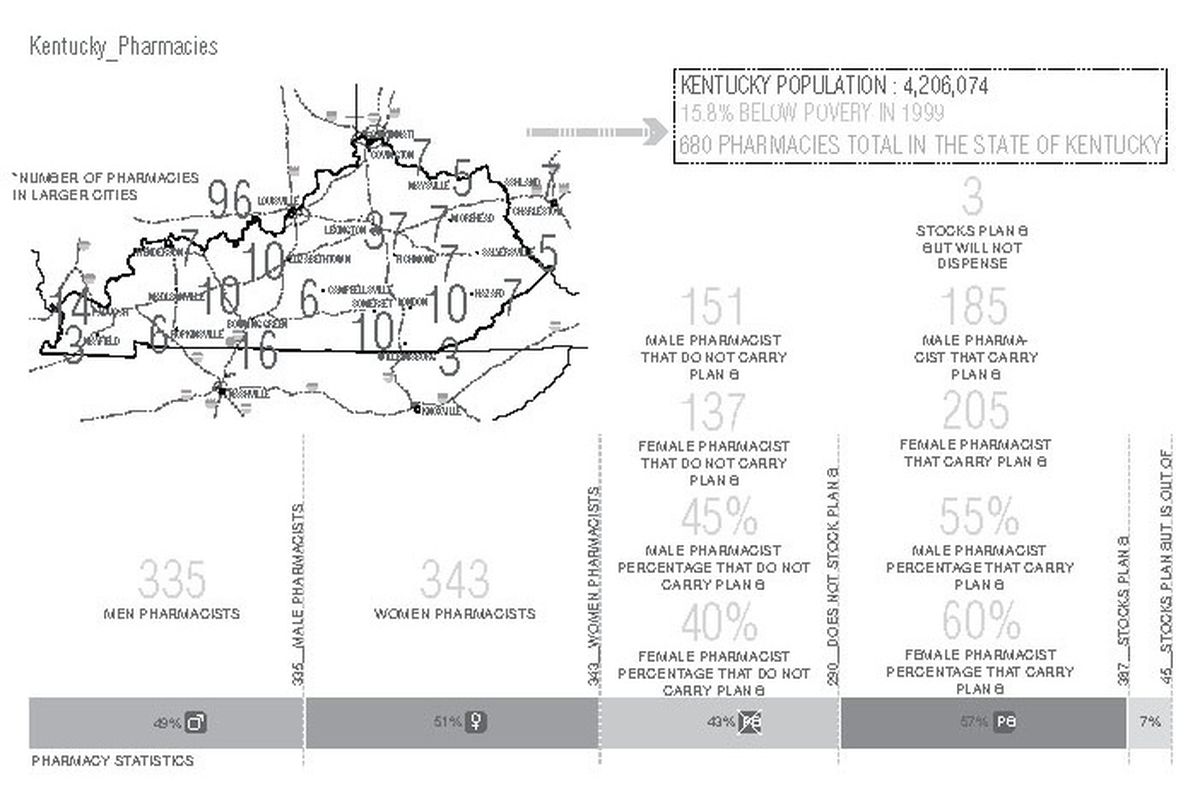

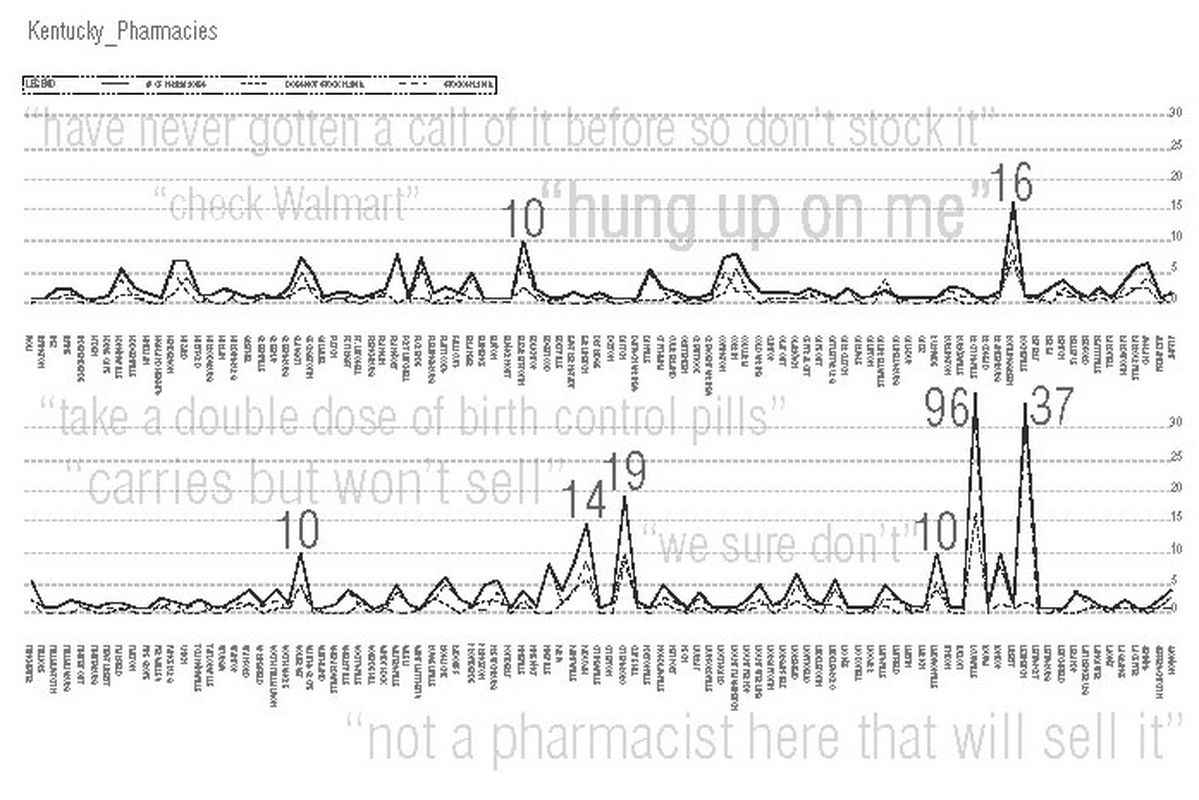

Brown’s forthcoming book Contested Spaces: Abortion Clinics, Women’s Shelters and Hospitals: Politicizing the Female Body will be published by Ashgate in June 2013. It looks at how legislation impacts and shapes the physical territory surrounding spaces of abortion in the US.

Currently Brown is working on Women in Architecture, a group she co-founded with Nina Freedman in New York to support and promote equity and diversity in the profession of architecture, and they are fundraising for this initiative.

Brown was the invited keynote speaker at Transform in Melbourne – a one-day symposium organized by Parlour as part of the ARC-funded research project Equity and Diversity in the Australian Architecture Profession. In her keynote address, she spoke about how we are framed by the discipline through the devices of privilege and patronage and how practices that question “normative design relations and their expected outcomes” are opening up our understanding of architectural practice and how we might practice architecture. Later, I had the pleasure of exploring the issues with her in conversation.

Tania Davidge: You work across multiple fields. How do you describe your practice when people ask you what you do?

Lori Brown feminist, activist architect.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Lori Brown: I think it has shifted in the past couple of years. I would have said I am a cross between an architect and an artist. Now, that’s still true, but I also think I am an activist architect. Activism has always been an interest of mine, but it has come out more now in the kinds of research I am pursuing, and in constantly trying to change the discipline in combination with making architecture more relevant for everyday people. I am becoming more engaged in activism around these issues – so I’d say I’m a feminist, activist architect.

TD: Where has this activism come from?

LB: I think it’s a response to my own experiences both as an architecture student where I had very few female professors and as a practitioner where I noticed there weren’t as many women I could reach out to. And over the years I have become more politically engaged. In New York I was working on incredibly wealthy people’s houses and really high-end commercial spaces and at some point it became kind of soul killing. I realized this was not what I had set out to do – I had really wanted to change the world. So, there was a shift [in my practice] and the teaching [at Syracuse University] corresponded to this shift. I realized I could start to take on projects that I really wanted to be invested in emotionally and politically.

My activism is also a response to my students. I had these great female students who were coming to me and saying “Where are the people like us? We’re not learning about them.” And I realized I could no longer just sit back and wonder too because I wasn’t seeing them either. So how could I help to change things and provide more exposure? It was a combination of these different influences that really set the trajectory.

TD: Your book Feminist Practices defines feminist practice as: “questioning normative design relations and their expected outcomes.”1 You write:

“Designing through feminist critiques questions whose voice the designer ultimately represents, whose vision is being created, and what the products produced need to be. In other words, if the “star” architect, who as students we were all taught to emulate, is no longer the working model, then what sorts of models should replace it?”2

One of the interesting things about this definition is that its critical focus, goals and aims are aligned with current conversations about expanded forms of practice and what the future of architectural practice might be. Can you comment or expand on this?

LB: My idea of feminism has been critiqued as a little bit “murky” and I totally disagree. I think my idea of feminism is more expansive. The future of feminism, I think, is to be more inclusive, it’s about social justice and yes, women are a part of that but we’re not the only part. It does a disservice to only say it’s about women because then it becomes about bashing men and I in no way would want to do that – we need them. We need their support. And when we improve things it improves things for them too. So I am trying to establish a far more expanded view and definition of feminist practice and in turn expand the way we think about what architecture can do and should be doing.

TD: What do you see the implications of this type of practice are? Firstly, for more traditional modes of practice and secondly, for traditional definitions of architecture.

LB: I think it is important to look at the way we practice in terms of the relevance of the profession. If we don’t become more inclusive – which is about our client base and who the audience is that we are engaging with and who should we be engaging with – we are just going to become decorators for the über-wealthy. And I say that in the most pejorative way. I think if we really want to take on some of the serious issues this is the perfect opportunity to do so. Issues of social justice, housing, environmental sustainability, these are all really critical issues where architecture should be at the forefront – looking at, speaking about, doing researching on and designing and building.

I never want us to lose the traditional sense of building but I think we [women] also have to be included when we think about diversity and what we bring to the table as design thinkers for the built environment. It’s not always about resultant form-making. In some ways the Transform symposium talked to that. We [architects] bring so much to the table in the way we’re taught, in the way we think about things as problem solvers on so many different levels. I think the discipline has to open up and accept that it’s not just about built form anymore.

There is a real entrenchment in not wanting to expand the way we define architecture because somehow it might dissolve or weaken what architects do; but we are already weakened. We have already given away so much of our expertise and our knowledge. We’re at a point where there is a real opportunity within all of the major issues where we can reclaim – or not even reclaim but stake out new territory.

TD: One of the issues I see with this exploration of expanded practice is how it’s funded. How can we be paid for the services we provide if we are exploring and creating new forms of practice: how do we work out how to place a value on that service?

I see this as a problem for the men practicing in this area also but as financial disempowerment is one of the key difficulties facing women in all walks of life (regardless of class) it is particularly problematic for women.

LB: I totally agree, the economics are crucial. And I don’t have the answers but I have been thinking about this. If expanded practice really engages communities and communities value this service, then there is opportunity for value exchange which includes some kind of economic model. I’m not suggesting we go back to some form of barter system, but I think there could be different ways to think about value exchange – if you are working with a community instead of an individual that’s a totally different set of relationships. I think back to Esther Charlesworth’s presentation at Transform, it is really interesting that communities are paying for these services, I don’t know how much they’re paying but clearly they’re paying. That’s a different kind of model that is really important to think about as we move forward. Because I agree, I’ve done so much pro bono work and I can’t do that anymore. There has to be a value exchange that’s monetary. I value that work but I realize it’s not being valued if you don’t pay for it. And that devalues our discipline even further.

So I think maybe it’s how we engage with the entrepreneurial possibilities of community development and even fundraising through crowd sourcing. Not that you could necessarily build huge buildings with crowd funding but there are alternatives out there that people are starting to deal with on a smaller level that may be able to be ramped up when you start to talk about larger scale projects. Larger community partnerships may be a way to also think about different economic models. It’s something I need to give more thought, but what would be the developed country equivalent of micro-financing? It’s something that needs to be pursued more aggressively.

TD: Part of your research explores practices that promote and support equity and diversity in other professions/industries.3 What are the key practices from other fields that you feel might make an impact on equity and diversity in architecture?

LB: The issue of negotiation is critical. If we can bring more awareness to young female students and women already out in the profession about how to be better negotiators and to speak up and speak out about what we are worth it will immediately start to change the conversation. I also think the engagement between the academy and the discipline is really critical. In the US there has been siloing between the two and not enough cross engagement. Parlour for me is so interesting because it’s reliant on both. It’s a really great model for me to take back to the States.

Another thing I am taking away from the research is that all of the case studies have begun with individuals and have then had larger impact. They all started at a small scale which is so encouraging and inspiring because it’s making a big impact. There are these small groups who are getting out there making a difference. We don’t need huge organizations to do this we just need to organise and speak to one another about what the issues are.

TD: Social media has been really empowering in relation to this.

LB: Yes. It helps to get all of these people together and whether they come to all the meetings or not they’re kept abreast.

TD: How do you feel your research has affected your design practice?

LB: I used to think about it in a more traditional way, now it doesn’t have to be about buildings. It can be about mapping things, revealing things, talking about possibilities and maybe speculating about spatial relationships but it doesn’t have to be about making it a building. I have the utmost respect for people who can build and build well because it is so difficult to create good projects and see them all the way through. Sometimes I miss that but I think there is something so energising about ‘hot button’ topics that have spatial implications and help people outside of the discipline think about the politics of space. That is where I am so much invested. It’s about gender right now, but it’s also about the larger social justice issue and the political ramifications of these kinds of interests.

TD: This is where your work on ‘Contested Space’ is so interesting. The project visualises the impact of the First Amendment right to free speech and other laws in relation to the contested territory surrounding abortion clinics in the US. What for many women creates a ‘walk of shame’ past a wall of anti-abortion campaigners for access to healthcare legislated by Roe vs Wade. Architects are visual communicators and the project helps people visualise the confronting spatial implications of public policy.

Pre-Easter anti-abortion protestors sidewalk queue in Louisville, Kentucky, April 2012.

Image: Nelson Helm, 2012

LB: One really interesting thing is now coming out of that work. Because of my interview with Diane Derzis, the owner and director of the only abortion clinic in Mississippi, I am in the process of putting together a competition for their fence. They have been weaving black plastic through this fence to provide more privacy for the women who use the clinic but it doesn’t provide enough privacy nor is it a good solution visually. In speaking to the director I mentioned that architects would really be interested in doing something with the fence and Diane is interested in this idea. I now need to research zoning and material issues because the state legislators and the larger anti-choice community don’t want this building to succeed and have created constraints specifically directed towards the clinic. The state legislation is completely anti-choice and many have publicly stated they seek to make the state abortion free – which is of course illegal, considering there is a federal law that legalized abortion in 1973. Because of this I need to make sure that I am very informed about what the project could be. I want to run a competition that could result in a something actually getting installed within the fence that would be effective – something that is a real spatial result of the research and raises the issue to a broader public.

TD: It’s interesting to me that you speak of running a competition rather than doing the work yourself.

LB: Running a competition will be more interesting in terms of raising awareness. The idea of the publicity is so interesting to me and there are so many different afterlives the products of a competition could have that could push the political space of the project.

TD: As an academic as well as an architect, what are some of the important lessons that you would like to see students take with them into the profession?

LB: I would like them to understand that they are political agents and that they have agency. Design is not a passive act, it is a critical engagement with community and you have to be cognizant of the power that you have and how you use it. What we do is really important. We have a responsibility and it’s not just about making the next great form, there are many other things that go into architecture. We need more people to use their agency to make positive change.

Transform: Altering the Future of Architecture was a one-day Parlour conference convened by Justine Clark, Karen Burns and Naomi Stead as part of the ARC-funded research project Equity and Diversity in the Australian Architecture Profession: Women, Work and Leadership. The project is currently working on Draft Guidelines to Equitable Practice with the Australian Institute of Architects, and Parlour is seeking feedback on them.

1. Lori A. Brown, ed. Feminist Practices: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Women in Architecture (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2011). 4.

2. Ibid. 4.

3. Practices that Brown’s research explored: She Says, Yale Law Women, The Wage Project and Girls Who Code.