In his seminal 1960 tome The Australian Ugliness, Robin Boyd describes the ideal relationship between architect and client: “Those who derive pleasure from architecture and have the means to indulge their taste would, as always, consult the artist-architect of their choice. He, as always, would create in form and space a sort of personal portrait of the occupants and himself.”

Bill Lyons, then an orthopaedic surgeon in his early thirties, was among those who read the first edition of The Australian Ugliness. Married with four young children, Lyons had purchased a block of land on a hilltop overlooking Sydney’s Port Hacking and sought an architect to design his family home. Lyons’ first choice was Harry Seidler, Sydney’s pre-eminent architect. He recalls walking into Seidler’s cavernous office, where the architect was installed in the far corner behind a vast desk, his demeanour that of “a man at his throne.” At the time, Seidler was working on his landmark Australia Square tower, and probably had little patience for a domestic brief. “I’m the architect,” Lyons recalls him saying. “I’ll design the house. You keep out of the road. When it’s finished, I’ll give you the key and that’s that.”

Put off by this encounter, Lyons decided to write to Boyd, who lived and worked in Melbourne, and ask him to recommend another architect. In his reply, Boyd surprisingly declared his own interest in the project. Flying back from Montreal, where he was preparing the Australian Pavilion for Expo 67, Boyd was due to transit in Sydney. The first meeting between client and architect was brief, but the two men had an instant rapport. Ten years Lyons’ senior, Boyd was a tall, well-spoken man with sandy hair and a “washed-out look,” recalls Lyons. He had a quiet temperament but a keen wit. He must also have been a good listener. “He only asked one question,” says Lyons, “‘In which room in the house could you accept no view?’ and I said ‘The study.’”

Lyons envisioned a Spanish-style house with a courtyard and swimming pool, and a space where his wife could play her grand piano and host musical soirees. “I wasn’t so interested in how the house looked to the neighbours,” he says. ‘I was more interested in privacy. [From] that first half hour [came] the formation of the ideas for the place. I had the preliminary drawings within a fortnight and we never really deviated.”

While the architect worked on the blueprints, his client built a meticulous scale model of the design. For the young doctor, here was a chance to realize a burgeoning interest in architecture. For Boyd, the project represented more than just a first Sydney commission. In his introduction to The Australian Ugliness, Boyd portrays suburbia as a failure of both aesthetics and ethics, “a country of many colourful, patterned, plastic veneers, of brick-veneer villas, and the White Australia Policy.” Had he needed inspiration while writing those words, then the streets of Port Hacking would have provided ideal fodder. Sydney’s conservative Sutherland Shire is a veritable badlands of what Boyd called “featurism”: a landscape of iridescent green lawn punctuated by oversized and eclectically ornamented brick-veneer villas. “‘Featurism’ was the word that absolutely sent him into a frenzy,” remembers Lyons.

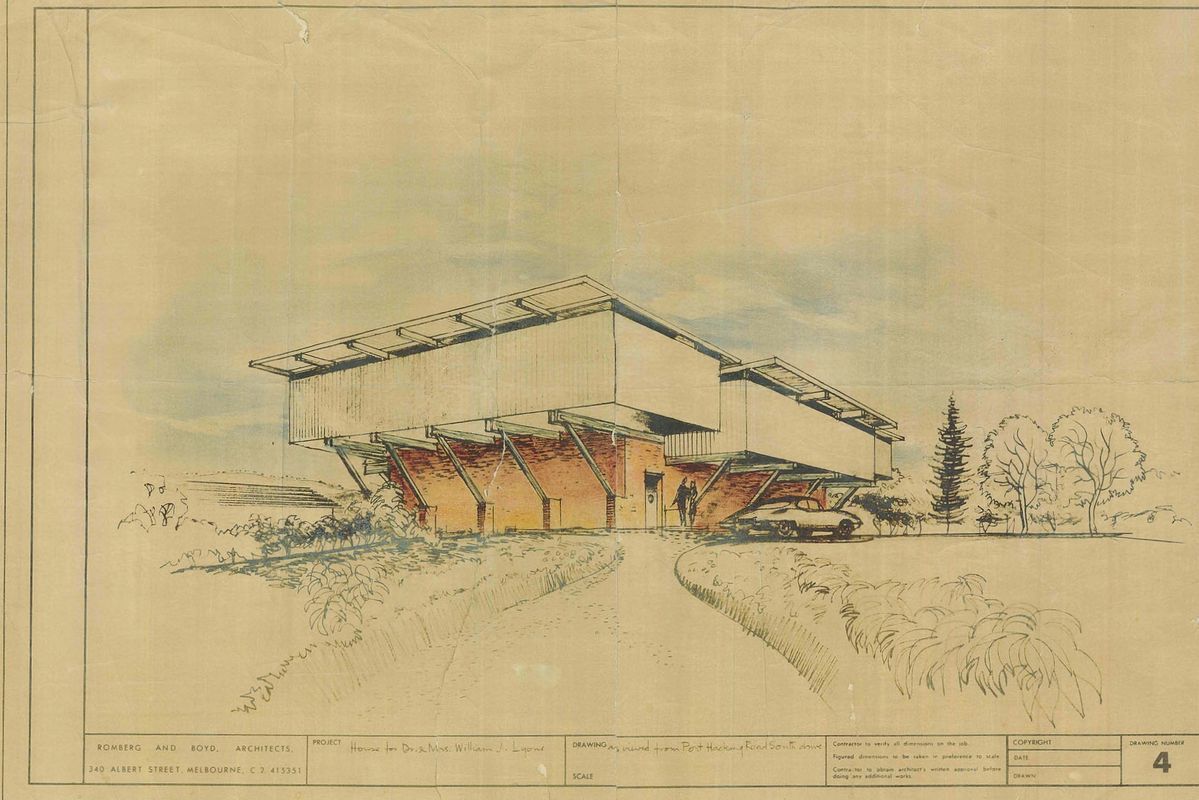

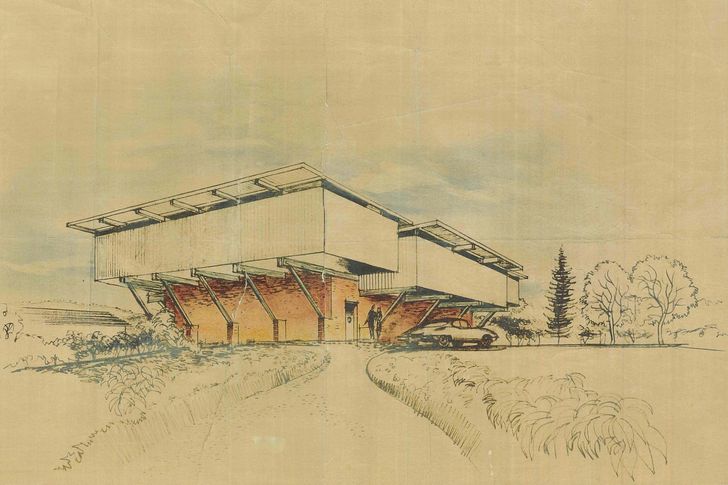

An original sketch of the Lyons House by Robin Boyd.

Design of the house began in 1965 and construction was completed in October 1967. Boyd delivered the courtyard home requested by his client. Inside, the house is low-slung and low-key. A single level of living and sleeping spaces is linked by a pool, deck and sunken entertaining room. Skillion roofs angle towards the pool to provide shade. Outside, however, is a different stor(e)y. Set back from the street, the courtyard floor is raised dramatically off the ground.

Supported by the post-tensioned concrete pool, the main structure is concealed within a non-load-bearing brick plinth, so that the house appears to cantilever on improbably narrow timber struts. Laundry, workshop, cellar and utilities are accommodated within the plinth, while the entry features a porthole into the pool. By elevating the house, Boyd enabled panoramic bay views, escaped the shadows from adjoining properties and created an overhanging eave that shelters cars. More significantly, every side of the house presents an almost blank face to the neighbours. By detaching from the ground, Boyd turned his back on the suburban context.

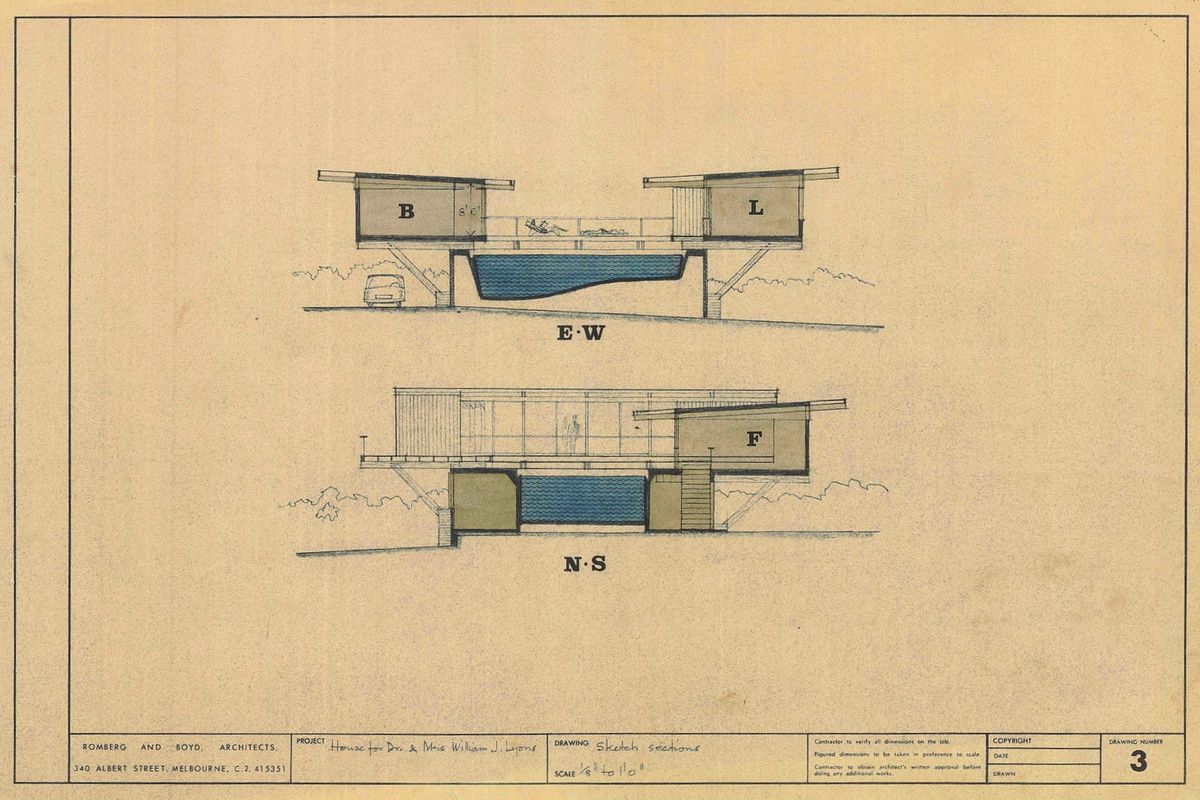

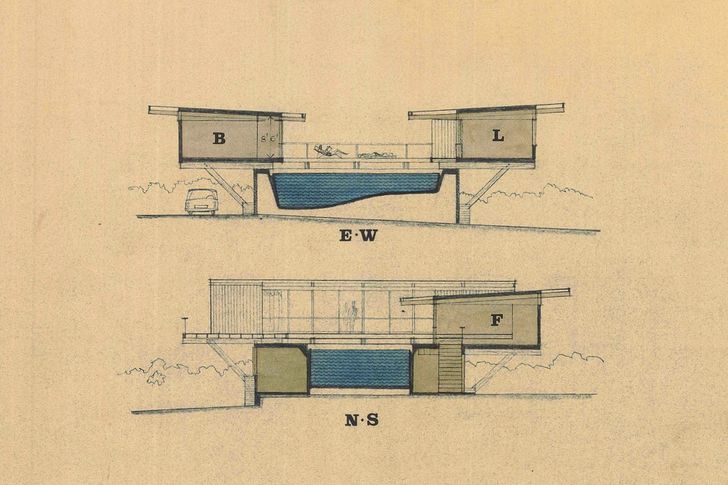

A section shows that the house is adventurous and unconventional, with living spaces suspended above ground.

Sadly, the architect died just four years after the project’s completion, and the house was to be his only Sydney project. Now in his mid-seventies, Lyons has long been remarried, and empty bedrooms play occasional host to visiting grandchildren. Recorded in Max Dupain’s photographs, interiors originally designed by Marion Hall Best have gradually given way to more homely furnishings. While the clarity of the plan is immediately evident, it takes close inspection to appreciate the house’s enduring qualities. From the engawa-like ambulatory corridor around the pool, to the internal post-and-beam structure and even the choice of matchstick blinds, there are frequent references to traditional Japanese architecture.

Craftsmanship is of almost Japanese standard, with rough-sawn timber joinery laboriously assembled to match the exposed structure. Ultimately, however, it is a humble dwelling appropriate for a young family. After forty-five years, it is the building’s exterior – gravity-defying, sculptural and unyielding – that still captures the imagination. “It was probably Boyd’s favourite house,” claims Lyons, and we’ll have to take him at his word.

Spanning the pragmatic 1940s, optimistic 1950s and idealistic 1960s, Robin Boyd’s career was brief but influential. Fittingly, the architect was equal parts pragmatist, optimist and idealist. The pragmatist Boyd launched the Small Homes Service, which distributed architect-designed house plans to the public. The optimist Boyd created some of Australia’s most radical individual dwellings. The idealist Boyd wrote books and a weekly column that promoted design literacy. Taking the plan, section and elevation of the Lyons House, we can draw a composite portrait of Boyd’s career. The plan of the house is as economical and rational as any of those devised for the Small Homes Service. However, the section of the house shows how adventurous and unconventional the house is, with living spaces suspended above ground to capture the view. Seen in elevation, the house confronts its context, reflecting Boyd’s antipathy towards the suburbs and the strength of his convictions.

Credits

- Project

- Lyons House

- Architect

- Robin Boyd

Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Site Details

-

Location

Sydney,

NSW,

Australia

Site type Suburban

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Category Residential

Type New houses

Source

Project

Published online: 25 Nov 2013

Words:

David Neustein

Images:

Courtesy of the Robin Boyd Foundation,

Peter Bennetts

Issue

Houses, August 2013