In 1899, pioneer landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted’s sons (and others) founded the American Society of Landscape Architects. Nearly seventy-five years later, Harvard University academic Norman T. Newton published his now classic Design on the Land: The Development of Landscape Architecture.1 In Australia, landscape architects would not have such a lengthy wait for a scholar to pen their professional history. Now, only forty-six years after the formation of the Australian Institute of Landscape Architects (AILA), the wait is over, with the publication of Andrew Saniga’s Making Landscape Architecture in Australia (MLAA). As Peter Walker and Melanie Simo observed, in the United States, “landscape architects have tended to be doers rather than critics and philosophers; they have tended to focus on the practical work at hand.”2 That is to say, they did much and wrote comparatively little. This circumstance was effectively mirrored in Australia, making Saniga’s investigation of the profession’s history a remarkable act of recovery.

MLAA is national in geographic scope. Temporally, the book first contextually traces the discipline’s origins to the seventeenth century and then shifts focus to the profession’s twentieth-century emergence and development. MLAA is chronologically and thematically structured into seven sections: Landscape Architecture in Context, Origins and Precedents, Spirit of the Pioneers, Uneven Paths, An Institute for Identity, Making Ground, and Contested Territories. Importantly, following one of the threads of landscape architecture’s Australian genesis led Saniga to a source that would be surprising to some: the sister profession of architecture. Rather than perpetuating the stereotypical proprietorial “turf war” between the two professions, he admirably celebrates the “garden design” achievements of, for instance, architect Harold Desbrowe-Annear (1865–1933) – also the designer of the University of Western Australia’s first campus plan – assessing them as “one of the more significant contributions to early-20th-century Melbourne” (page 33). As Saniga appreciates, many exquisite examples of landscape architecture were authored by architects. Throughout his narrative, Saniga skilfully identifies and unravels the knots of cross-cultural influences that have shaped the profession. Within this context he considers, for instance, émigré landscape architects and their projects. Of all these, for me, the work of Danish-born Paul Sorenson (1891–1983) is a standout. His modern gardens of the 1930s, with their crisp, bold geometries, today seem undated, if not timeless. Saniga’s astute inclusion of Sorenson marks one of the first recognitions of his work’s significance in years: peculiarly, until now, his gardens have attracted little professional attention, perhaps because Sorenson had no interest in making bush simulacra. After all, gardens, as critic William Howard Adams reminds us, are “nature perfected.”3

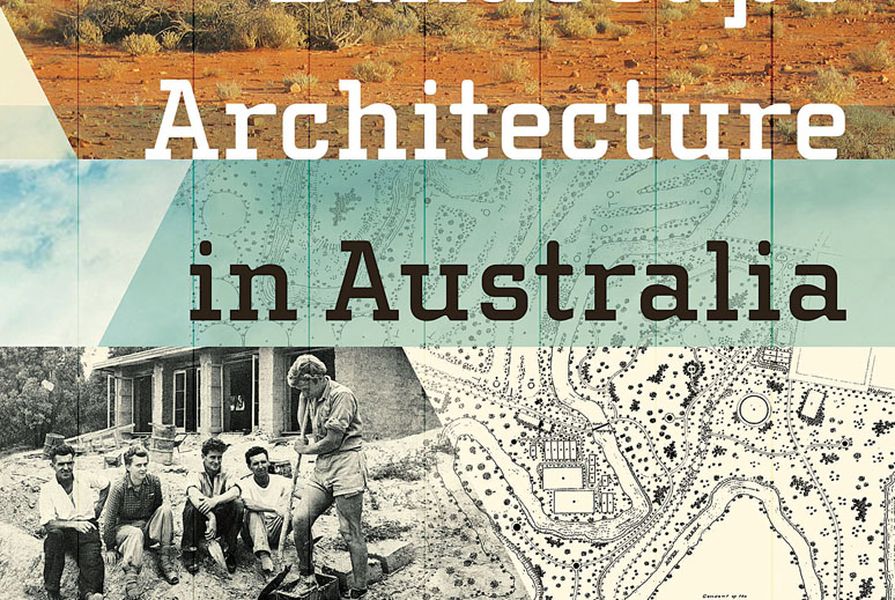

Until now, literature related to the history of Australian landscape architecture has tended to focus on individual designers and garden design, the latter usually considered through the lens of “style.” MLAA’s outlook, by contrast, is broader and more comprehensive in scope, and considers a gamut of project typologies (old and new) ranging from, for instance, gardens, parks and suburbs to landscape reclamation, assessment and urban design, and their often multiple authors. The book is profusely illustrated with photographs, plans and other drawings, albeit and disappointingly only in black and white.

Most significantly, for me at least, is that MLAA entrenches the Griffins in the history of Australian landscape architecture, with Burley Griffin amounting to an Australian Olmsted of sorts. (Burley Griffin, in his native United States, remains little more than a proverbial footnote in, paradoxically, the canon of not landscape, but architectural history.) “Americans Walter Burley Griffin (1876–1937) and Marion Mahony Griffin (1871–1961),” Saniga wrote, “were the first in Australia to start using the title ‘landscape architect’ in an official context,” marking the “unequivocal introduction of landscape architecture to Australia” (page 35). This was a view apparently held by the profession’s founders themselves. Although little known and seldom published, the AILA’s coat of arms features a griffin, alluding to Walter and the national capital. Indeed, Saniga distinguishes Canberra as “the first large-scale regional work that could be classified as a landscape architecture project in Australia” (page 35). A century later, it remains Australia’s only globally significant example of landscape architecture. Canberra’s significance, however, was not limited to the Griffins. As Saniga demonstrates in a section chronicling the postwar achievements of the National Capital Development Commission, the capital also became a canvas for modernist landscape architects such as Richard Clough (1921– ).

Overall, Saniga’s survey of more than a century’s landscape architectural works and their authors is a feat nothing short of magisterial. This landmark study will be required reading for my students and no Australian landscape architect’s library is complete without Making Landscape Architecture in Australia on its shelves.

Andrew Saniga (New South Books, 2012, paperback) 400 pages. RRP $69.99.

1 Norman T. Newton, Design on the Land: The Development of Landscape Architecture (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971).

2 Peter Walker and Melanie Simo, Invisible Gardens: The Search for Modernism in the American Landscape (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1996), 4.

3 William Howard Adams, Nature Perfected: Gardens through History (NY: Abbeville Press, 1991).

Source

Discussion

Published online: 25 Jun 2013

Words:

Christopher Vernon

Issue

Landscape Architecture Australia, May 2013