Marina Tabassum founded URBANA in 1995 with Kashef Chowdhury, and won competitions for the Independence Monument of Bangladesh and the Liberation War Museum. As principal of her own practice, Marina Tabassum Architects in Dhaka, Bangladesh, Tabassum was recently in Perth for the 2014 National Architecture Conference – Making – where she spoke with Melbourne architect Rowena Hockin about her the oversupply of women architects in her country, and how she cornered herself into the incongruous niches of mosque and residential design.

Rowena Hockin: It’s great to have a strong representation of women at the conference and also a strong representation of non-European practitioners. I would like to ask you about your story, about being a female architect in Bangladesh. What’s your experience of practising … what are the contextual and gender issues you face?

Architect Marina Tabassum, guest speaker at Making 2014 in Perth.

Image: Peter Bennetts

Marina Tabassum: Well I have to go back a long way. Bengal has always been a bit different from the overall Indian subcontinent. We’ve had matriarchal societies for thousands of years. If you look at the Indigenous people who live there, they are all from matriarchal societies. I think it also has to do with our climate. It’s a very moderate temperature where you are not physically challenged to take up any kind of work which is not fit for the physicality of a woman.

Women and men have always been working side by side, so women were never looked down upon or thought of as a secondary or someone who needs to be protected. And I suppose this whole notion of men-women issues came when new religions came into our situation, because those are more patriarchal societies and developed in those situations, so there was a sort of imbalance that was created.

RH: And that imbalance rubs against the innate systems that were there … Does that create friction?

MT: It does, and there is a friction, but also a resistance from women, and men equally I think. Men do not want women to sit around home and just do nothing. They want them to be active, and women want to be very active in economic terms, so women work, in every possible situation. We have super-rich, rich, and very poor people as well, but in every situation everybody has work to do in some way or the other. So women are working and are financially solvent by themselves, which is a kind of liberty that we have had all through.

I’m third or fourth generation educated…my mother was an educated woman, my aunts, my mother. They were doctors, teachers. It was expected that I would make something out of my life, and my cousins and sisters, they are all doctors or engineers or something of that sort. I’m the only one who is an architect.

RH: Why did you decide to study architecture?

MT: It was sort of by chance you could say. I didn’t have any dream as such of what I wanted to be, and in my day the options for higher education were very limited: engineer, doctor or architect, or pursue something else. I had a very bad high school result, so my only option was architecture.

RH: Were there a lot of other women studying architecture?

MT: Oh yes, we had more women than men. Actually it’s a concern for us that we have so many women getting into architecture and not enough men. Women are absolutely fantastic to have in the office: they are responsible, very systematic and everything, but they don’t come to practice permanently. Either they drop out or do a balancing act between supporting their family at the same time as doing a nine-to-five job. I think practice is never a nine-to-five job, it’s 24-hour work.

RH: How many female architects are there actually practising in Bangladesh?

MT: Oh they’re very rare, maybe ten or fifteen, at most.

RH: In terms of the work that you do, you seem to have a broad spread of project types. You’ve worked on residential, apartment buildings, some industrial, mosques. Is that a typical spread of work for an architect in Bangladesh?

MT: Not really, no, it’s just me. I decided not to work for real estate developers, because they don’t let you do much, and there’s hardly anything to challenge you. So I’ve done maybe two or three of those projects, where there was a bit of a challenge, but otherwise I avoid developers. That means you don’t get much chance for public projects, because they are done by the government, except when you have competitions (that’s how I got the Museum project). So I’ve kind of niched myself into a little corner…

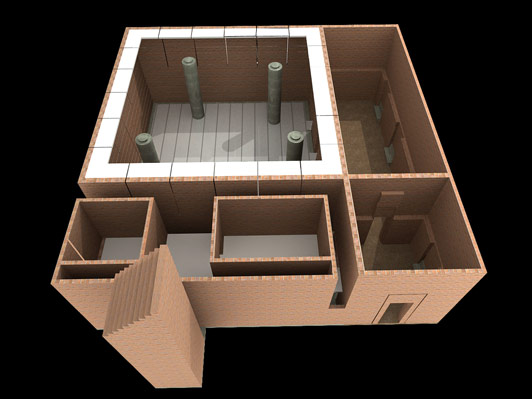

Baitur Rauf Jame Mosque by Marina Tabassum Architects, commissioned by her grandmother in commemoration of Marina’s mother.

Image: Courtesy Marina Tabassum Architects

RH: But within that corner you get to work on residential projects?

MT: Yes, the thing is, those that come to me to do a building know my taste, and the way I work, so the clients generally come, and I always look for something interesting and challenging as a project, just not anything.

RH: Your work on mosque projects is very interesting to me … I don’t think in Bangladesh that would be a common thing to have a female architect designing mosques?

Baitur Rauf Jame Mosque in Dhaka, Bangladesh by Marina Tabassum Architects. Commissioned by Marina’s grandmother in commemoration of her mother.

Image: Courtesy Marina Tabassum Architects

MT: I did a guideline for mosques in Abu Dhabi, and while Bangladesh is secular in that sense, I was worried about how it would be taken – a woman dictating how their mosque should look. With many mosques more or less destroyed, we did an extensive study of all their different vernacular architectures from coastal to desert, starting from Abu Dhabi, to Ras al-Khaimah and all over the UAE, combining them with an analysis of material, construction technique, to arrive at an essentially what makes an Emirati architecture.

So based on that sense we gained an idea that this is how you can take this and put it in a more contemporary use. In a way I gave them back a language that was lost, recreating it in a contemporary sense, so it was accepted quite normally and naturally. I think if you have substance, the whole idea of a woman and man disappears. That was really interesting work that I really enjoyed.

RH: Have you seen that translated into built forms?

MT: Well, the idea was to do this guideline and to give it to the architects who were actually practising there. Obviously every architect differs, language differs, but the basic ideas they have been able to grasp.

RH: I see in your work an essence and a restraint, and a very strong and consistent materiality. How do you determine the materiality of a project?

MT: It depends on the project. I’ve used a lot of brick predominantly because it is the only material we have. We don’t have stone and we have a labour force that is very cheap, so when we have budget projects (which most of my projects are except for the Museum), brick is what we use. You can take a very simple material and by the action of your own creativity and innovation take that to any level you like. I’ve worked in concrete: the Museum was done in concrete and then the mosque has a prayer space in concrete because it has a large span and couldn’t be done in any other way. I’ve also worked in mud: we are building the while resort project in mud.

Tower of Light, Independence Monument by Marina Tabassum Architects.

Image: Courtesy Marina Tabassum Architects

RH: What are the research factors that you pull together when you are synthesising ideas into a building? What things do you you look to explore?

MT: Lots of things actually. Mostly the history of the place, that is very intriguing to me. I always try to find the history of the land and the region, the context and the climate, which is where I try to find my elements, my ingredients for cooking; architecture is cooking. And also the history of the people who I am building for. Architecture has very limited answers as far as I see. If you look deeply into the site, the context, the program, it’s already there, you just have to look into all those little corner to find it out.

RH: So when you start a project, what would be the first move that you would make – would it be to go to site?

MT: First to site. This is the most important to me, spending time to connect with the site, and around the site. This gives you a lot of answers. And then program: we try to dissect the program. One way of my work is, if I take a mosque, I wouldn’t just take a mosque, I would go back to the first stage of what was a mosque? How did it come into being, what was the function? Then you can let go of all the extra liturgies that are associated with those things, go back to the beginning and start something interesting.

That is not to underestimate the history or legacy of mosque making, it’s a rich legacy, but they have to come together at some point and only then it becomes relevant. I feel that we are just updating ourselves through time. You cannot just build something out of nowhere and it doesn’t make sense to do that. So if you want to update then you have to follow through the history.

RH: That’s a lovely quote. Thank you.

Making 2014 was presented by the Australian Institute of Architects.