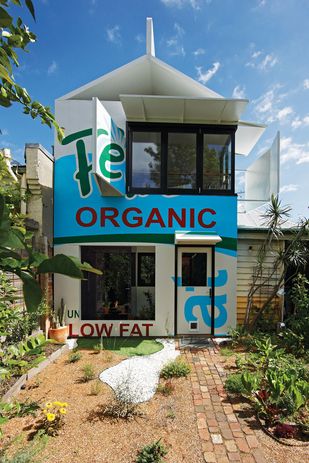

From an outdoor table at a bustling Lygon Street cafe, one can just make out the thumbs-up symbol on the top of the bright white, “Tetra Pak” hip-gable roof. Amid retail frontages, sawtooth factory roofs, faded Victorian terraces and gaudy signage, the Milk Carton house extension sits comfortably on the eclectic Brunswick skyline.

Light fitting in the form of a milk drop.

On the inside, it is a modest and pragmatic renovation – clean, white spaces (complete with white droplet light fittings) consisting of a ground-floor bathroom and toilet with stairs to a second-level studio and work space. The house retains the functional feature of the previous existing passage that neatly connects the garden at the front to the paved yard at the rear. In terms of structure and materials it is nothing overly complicated – flat steel sheet with a Colorbond finish. A concrete ground floor and double-glazed windows with sunshades upstairs help keep the building cool and economical to heat. The windows and privacy (overlooking) screens are so minimal and neat, they look as if they have been scored and cut out with a giant Stanley knife.

The clients love living in the milk carton. Not only is it a well-designed, graceful and practical space, but it is unique and enigmatic at the same time as simple and unpretentious. By designing something so absurd as a giant milk carton, architect Simon Thornton has effectively negated the notions of class-based lifestyle symbolism which so often accompany a flashy new extension.

Simon refers to the work as “fiction architecture,” which is both fitting and challenging. Fiction is make-believe but good fiction has a way of heightening our understanding of the everyday. As Simon says, “It’s fiction because it couldn’t really happen.” True, you couldn’t live in an actual milk carton. However, in this post-Baudrillardian age of super simulacra, anything can be made realistic, huge and livable. So it becomes almost paradoxical calling it fiction architecture – because now it is real. A new story is written and is brought to life by the people inside it.

A “spilt milk” path of white pebbles.

Image: Mark Munro

When presenting the model to the clients, Simon brought along an actual empty milk carton, complete with cuts and scores for windows and doors. The clients initially thought that Simon, being the savvy environmentalist that he is, was saving materials, but soon learnt that this was what he proposed, literally. It didn’t take long before they were both wholeheartedly on board, actively collaborating with organizing the sign-writing, deciding on the fictitious use-by date of 30 February and designing the witty “spilt milk” landscaping in white pebbles at the rear.

The role of fiction architecture should not be confused with the nonfiction agenda of the purely representational Australian “big” things (pineapple, banana, merino, etc.), which act as super-sized, kitsch retail outlet or advertising icon for that actual item. The milk carton is not aspiring to be the “Big Milk of Brunswick.” It fits more neatly into the parameters of folklore and fairytale, like the old woman who lived in a shoe or tiny Thumbelina who slept in an “elegantly polished walnut shell.” (Thumbelina, Hans Christian Andersen.)

Perhaps it is more useful to look at the milk carton as hyperreal or surreal. Within the world of art, super-sizing mundane objects is commonplace from pop culture onwards. Many of Swedish pop artist Claes Oldenburg’s works spring to mind, particularly a giant pair of black binoculars that were commissioned by Frank O. Gehry and Associates for the entrance to the Chiat/Day Inc. building in Venice, California in the early 90s. The work acts seamlessly as a bridging chamber for the building as well as a sculpture in its own right. It is a playful yet practical extension, much like the milk carton. Oldenburg’s work played on the notion of the pathetic monument, making the humble heroic and vice versa – deliberately subverting the serious traditions of public sculpture and hierarchy. Even before pop, the surrealists employed distorted scale as another means to elevate everyday objects and symbols to a heightened reality or understanding, akin to dream states. In René Magritte’s 1952 painting Personal Values, a giant comb sits on the bed next to an oversized wineglass and other personal items of distorted scale, making us question the familiar and its worth. The word surreal actually means “above reality.” The surrealists believed that there is an element of truth revealed by our subconscious minds which supersedes the reality of our everyday consciousness.

Personally, I think the symbols in our built environment are becoming more conservative and homogeneous by the day, especially in this time of eco-puritanism and repetitious rationale. Make-believe and play are the perfect antidote. If, in the words of Albert Camus, “Fiction is the lie through which we tell the truth,” then fiction architecture might be the reality in which we can live a dream.

Products and materials

- Roofing

- Lysaght flat steel painted in Colorbond ‘Surfmist.’

- External walls

- Lysaght flat steel painted in Colorbond ‘Surfmist’; DuPont Tyvek wall foil.

- Internal walls

- James Hardie Villaboard; Boral plasterboard.

- Windows

- Advanced Architectural Windows double-glazed aluminium windows, powdercoated and painted ‘Black Satin’.

- Doors

- Hume Doors and Timber; Advanced Architectural Windows.

- Flooring

- Embelton bamboo; concrete with a steel trowel finish, acid-stained.

- Bathroom

- Custom shower screens; black-painted glass.

- Other

- Bench in passage made from old outdoor toilet door.

Credits

- Project

- Milk Carton House

- Architect

- Simon and Freda Thornton Architects

Alphington, Melbourne, Vic, Australia

- Project Team

- Simon Thornton, Clara Friedhoff

- Consultants

-

Builder

Integrated Construction Services

Building surveyor Metro Building Surveying

Engineer Robert Brotchie and Associates

- Site Details

-

Location

Brunswick,

Melbourne,

Vic,

Australia

Site area 279 m2

Building area 146 m2

- Project Details

-

Status

Built

Design, documentation 12 months

Construction 9 months

Category Residential

Type New houses