<b>REVIEW</b> SHANEEN FANTIN <b>PHOTOGRAPHY</b> ANDREW LANE

Archway of crossed spears above the KASH entrance gateway, a modest monument to Kalkadoon culture. The Kalkadoon are described as the people of the Eyre region between the Georgina and Corella Rivers, and are well known for the ferocious and courageous battle they fought against the Native Police in 1884.

Fence detail near the front gate.

KASH is one of only two alcohol rehabilitation centres in Queensland that accommodate families. From left to right: Troyden Johnny, Jacqueline Calligan, Kevina Anderson, Tyrell Swann and Donna Daly (behind).

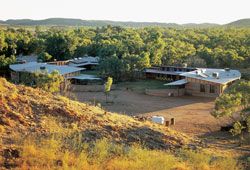

Looking over the facility.

View looking over the new accommodation to the hills. Each wing incorporates external sitting and living areas.

A windbreak wall curves around a ramp.

The art of cultural appropriation in the existing building.

Courtyard detail.

Figure on the gateway fence.

Banded block work and vertical sunshades.

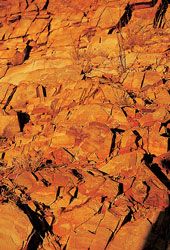

The block work colours come from rock strata in the nearby hills.

The courtyard promotes social interaction.

The generous verandah.

External living space.

Verandah seat outside the counsellor’s office.

IN TRANQUIL BUSHLAND on the outskirts of Mount Isa I visited a place where people told me astonishing stories of drinking, drug taking, violence, gaol terms and relinquishing their children to “services”. These people are not homeless, itinerants, “bikies” or “parkies”. They are residents of Kalkadoon Aboriginal Sobriety House (KASH), an Indigenous alcohol and drug rehabilitation centre. As the residents of KASH offered their personal histories in open and descriptive language over a cup of tea, their children spun bicycle tyres raucously in the sandy courtyard of the centre’s new extension designed by Deb Fisher Architects.

KASH has been offering support, education and rehabilitation services to residents of the Gulf of Carpentaria and western Queensland since the late 1970s. However, until 2001 the centre operated from an unremarkable set of buildings: simple concrete block structures accompanied by long, low-elevated fibro-and-timber sleeping quarters, otherwise known in Queensland and the Northern Territory as “Mary K” buildings. For many Aboriginal people “Mary K” buildings are associated with institutions, mission stations, the Stolen Children’s generation, and temporary lockup. The residents of KASH likened the “Mary K” sleeping quarters to a prison: all lined up, no room for family, and skinny verandahs.

In 2001 the Office of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health, part of the Australian Government’s Department for Health and Aging, funded the demolition and replacement of the accommodation wings of KASH, while Aboriginal Hostels contributed further funding for furniture and equipment. The consultation and design process was lengthy but not without opportunities for significant outcomes, architectural and social.

Deb Fisher was engaged to design the new accommodation with Maunsell Australia (project manager) through a procurement process managed by Arup for the Australian Government. It is worth noting that projects like KASH are not the outcome of one visionary human being. They are collaborative efforts in which the Aboriginal organization, architect, project manager, government agent and various government departments communicate regularly to ensure that projects are adequately funded and designed to meet the organization’s needs.

The new accommodation wings of KASH are hidden from view when entering the facility. The front gate is a modest monument to Kalkadoon Aboriginal culture and tradition. It has an archway of crossed spears and gates that support decorative silhouettes of native animals – an Indigenous interpretation of a cattle station gateway.

After winding down a gravel track through mulga and spreading eucalypts, past a brightly coloured house (the education and training centre), a small set of buildings and structures emerges through a high weldmesh fence topped with barbed wire. The manager of the centre explained that the fence was not to keep the residents in but to keep unwanted visitors out. Beyond the second gate is the vegetable garden, car park and octagonal shade structure for outdoor meetings. The new buildings are well camouflaged behind the layering of these rough-hewn elements. The juxtaposition of recent construction against kitchen wire, tin fireplaces and brush-clad shelters invokes a domestic and non-institutional quality in the new buildings.

From the eastern hills behind the centre, the new buildings sit comfortably in the landscape. The extension consists of two shallowly curved buildings with wide internal verandahs that overlook a turf-and-sand courtyard. The structures are low-slung and wide, accentuated by banded block work in charcoal and ochre. The block work colours mimic the surrounding landscape and Fisher drew the colours from the shaly rock strata of the nearby range. The scale and linearity of the courtyard edge are cleverly reduced through a variety of devices including different roof heights to delineate sitting and walking spaces, and the use of bright colours and decorative balustrading. Fisher says that the form of the balustrading was inspired by the seed pod of a local tree, but the residents I spoke with concurred that it must be a boomerang motif, although the colour is surprising for a boomerang. Each wing contains seven bedrooms (including ensuites) large enough to accommodate families, a laundry, a counsellor’s office and a variety of externally oriented sitting spaces that provide built-in tables and chairs, steps and windbreak walls. Although curvilinear in form, the new buildings and courtyard space were derived less from a romantic notion of organic Aboriginal architecture and more as an oppositional statement to the previous dormitory-style accommodation. The previous building ran in straight lines and offered mingy internal spaces with no relationship to the external environment. The new buildings hug the ground and provide generous but protected indoor and outdoor living spaces.

The arrangement of the bedrooms is generic, but flexible enough to enable clients to organize where existing and new residents should sleep. KASH is one of only two alcohol rehabilitation centres in Queensland that accommodate families, and this is reflected in the size of the new bedrooms and how the residents organize themselves spatially in the facility. For example, single men usually occupy rooms in the older buildings, while single women will often share with a family from their home community. Doomadgee people, who comprise a high proportion of clients, usually sleep in adjacent rooms, but always some distance from Lake Nash people. Those clients from the east side (Kowanyama, Townsville and Cairns) sleep near one another, but prefer to be away from people from the Territory.

During our visit the centre hosted sixteen children (twelve younger than school age) staying with their parents. The general approach to improving a resident’s health and wellbeing is that the entire family must be involved in the rehabilitation process, not only those with substance misuse problems. Having children in the centre creates an energetic and positive ambience, rather than the empty stillness that can emerge with the absence of children. Lloyd Kyle, the CEO of KASH, says that the new buildings have raised the confidence of the clients and contributed to their welfare. There are comfortable spaces for sitting and yarning facing north and east, well lit by the winter sun but protected from the bitter southerly winds. The courtyard promotes and facilitates social interaction, which Fisher and Kyle believe to be an important part of the rehabilitation process, and at the same time allows children to play freely under the watchful eyes of their parents.

The apparent success of Fisher’s design of the new buildings at KASH demonstrates how architecture can contribute to social change. The new quarters at KASH have increased the confidence of the centre’s clients. Concurrent with the design of the new accommodation has been the implementation of improved rehabilitation, training and education programmes by KASH staff. But how much of the increase in client confidence is attributable to the design of the facility compared to its “newness”? Is it only that KASH now has something other than a “Mary K” dormitory for clients to sleep in? From an holistic perspective the new facility at KASH offers more than just a clean shell for living in. It functions well climatically and socially, providing protected outdoor spaces that are important to the maintenance of Aboriginal culture. It complements the site and surrounding landscape, and it supports the provision of counselling and training programmes by facilitating interaction, conversation and client maintenance of the facility.

The relationship between the programmes implemented by KASH and the architecture could almost be considered mutually inclusive, or at least co-supportive. Aboriginal and Islander substance misuse and dependency are increasing issues for Australia. The new facilities at KASH provide a supportive and responsive environment in which people can begin their journey to wellness.

DR SHANEEN FANTIN IS A PROJECT MANAGER AND ARCHITECT WITH ARUP, CAIRNS. SHE HAS WORKED ON PROJECTS WITH ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER PEOPLE FOR THE PAST TEN YEARS. ANDREW LANE IS AN INDIGENOUS PHOTOGRAPHER WITH INTERESTS IN ARCHITECTURE AND REMOT

Project Credits

KALKADOON ABORIGINAL SOBRIETY HOUSE

Architect Deborah Fisher Architect—project team Deb Fisher, Nicole Ewing, Shaun Cassidy. Project manager Maunsell Australia. Structural and electrical engineer Maunsell Australia. Hydraulics engineer Steve Paul and Partners. Mechanical engineer Ashburner Francis. Cost planner Douglas Stark.