One of Melbourne’s oldest parks, Queen Victoria Gardens, has the unfortunate fate of being wedged between somewhere and somewhere else. With the attractions of the Myer Music Bowl and Melbourne Botanic Gardens to its east and the NGV International across St Kilda Road to its west, for all its leafy charms the park is more byway than destination, a condition which over a century’s worth of accumulated civic gewgaws (a flowering clock! Bronze water nymphs! A statue of Queen Victoria hewn from three kinds of rock!) has done woefully little to ameliorate. With the launch of a new initiative that hopes to raise the public profile of architecture and design, however, all that looks set to change – for four months of the year, anyway.

The initiative is the MPavilion. A ‘public-private partnership’ between fashion doyenne and philanthropist Naomi Milgrom’s eponymously named foundation, the City of Melbourne and the Victorian State Government, the MPavilion is described by its organisers as a Melbourne take on London’s popular Serpentine Pavilion. Much like the Serpentine, the MPavilion will be a temporary pavilion in a park, designed by an architect. That, for now though, is about where the similarity ends.

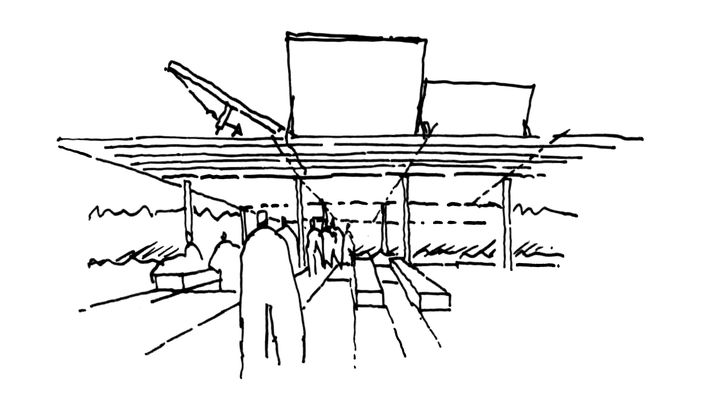

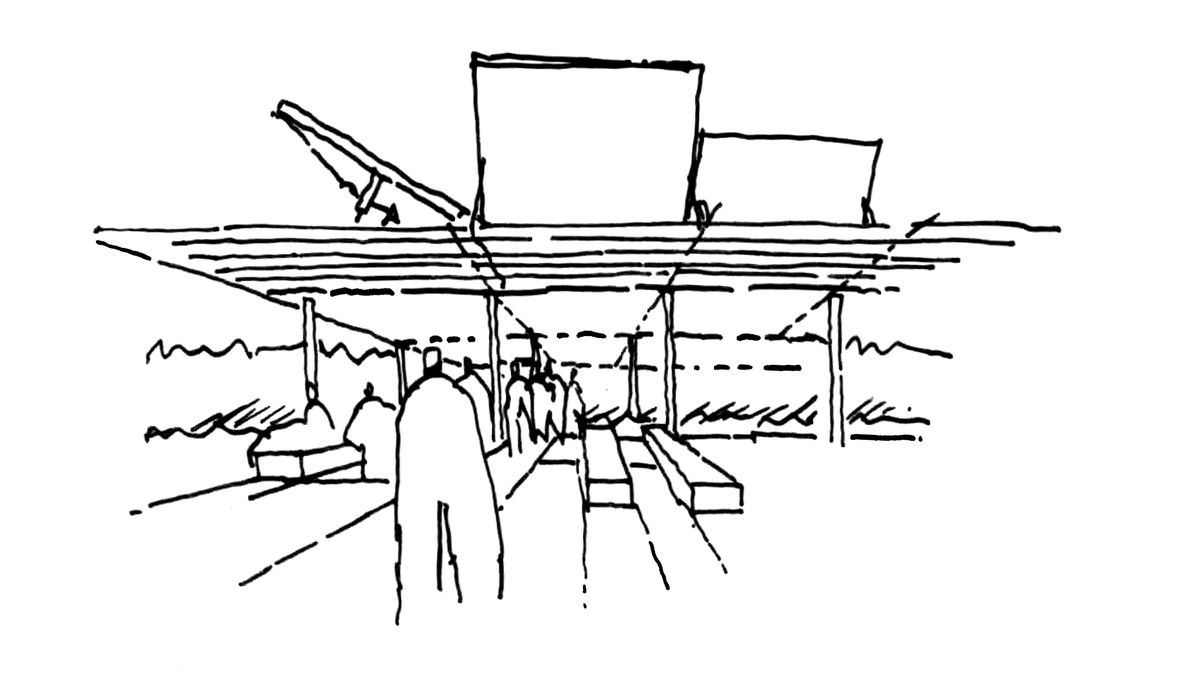

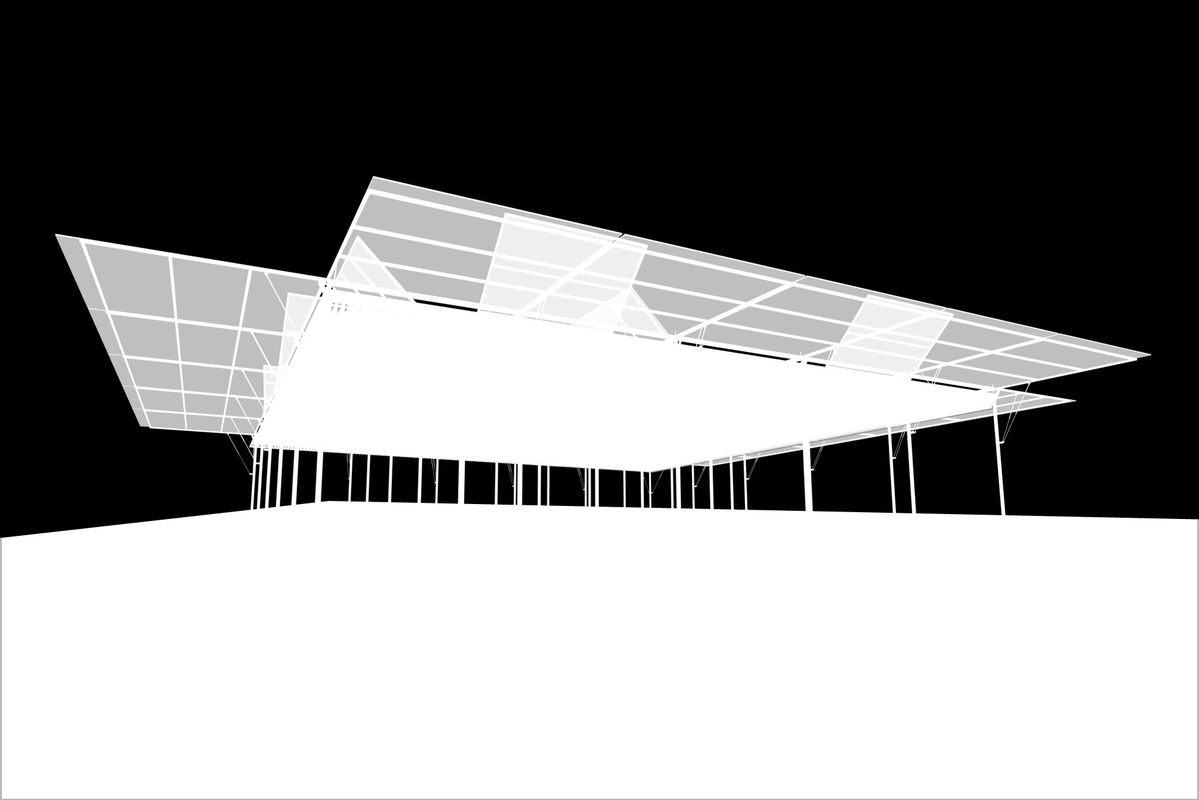

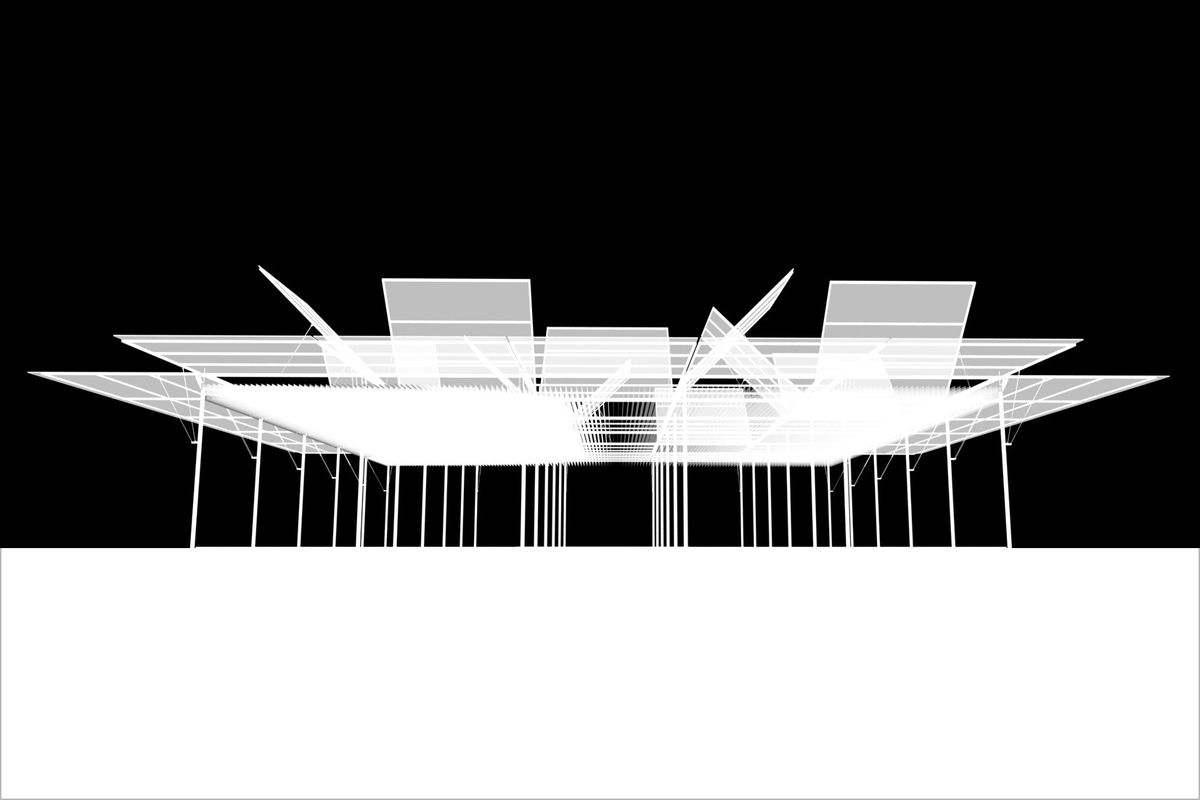

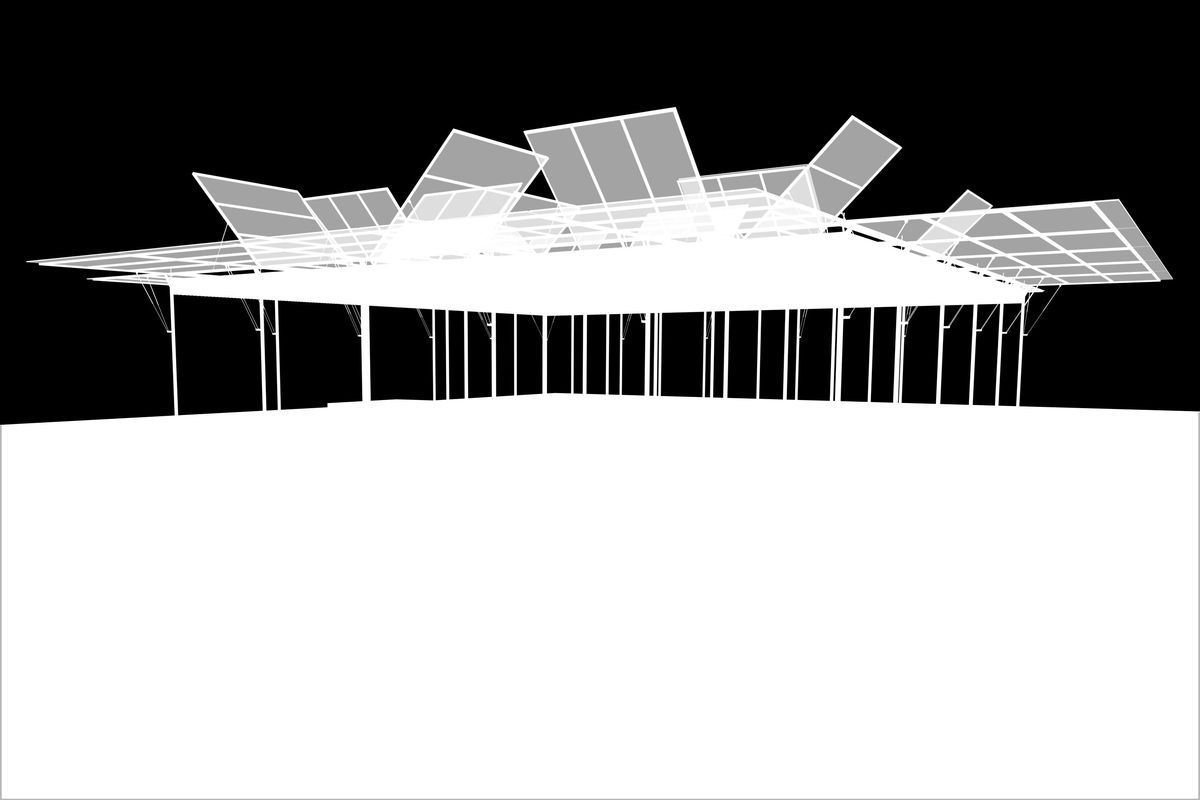

Sean Godsell’s sketch of the new MPavilion.

Image: Courtesy Sean Godsell Architects

For the period of every northern summer, the Serpentine program sees an internationally regarded architect construct a temporary structure in London’s Kensington Gardens. It’s an event that plays on the English tradition of the garden folly, albeit with a calculating twist – the brief makes very few programmatic or functional demands of the architect, allowing the pavilion to become a singular expression of their ideas and sensibility. The Serpentine is intended as a kind of provocation, then, but one given added pointiness by the fact that the architect responsible has, for whatever reason, yet to build in the UK.

Much like the Serpentine, the organisers describe the MPavilion as an annual commission for a ‘striking, original and sculptural’ summer pavilion from a leading international architect. If that’s the ambition, then the fact that the first commission was awarded to Melbourne architect Sean Godsell, for a structure inspired by ‘outback sheds and verandahs’, sends mixed messages. As Naomi Milgrom, chair of the Naomi Milgrom Foundation, said to me on the day of the program’s launch, ‘It was easy to commission Sean for the first pavilion – I have the greatest respect for his values, the rigour around his work, the discipline. It seemed obvious that he was the quintessential Australian architect.’

While we could debate the Australian-ness of Godsell’s architecture (just how many of the prospective Melburnian visitors to the MPavilion, you can’t help but wonder, would have come within sniffing distance of a sheep shed?) few architects, with the exceptions perhaps of Glenn Murcutt and Philip Cox, have done as much to reify the mythos of a ruggedly Arcadian, authentically ‘Australian’ architecture in the international consciousness as Godsell. His pavilion will likely make for a happy match with the idyllic, vaguely pastoral setting of the Queen Victoria Gardens. Given his notoriety, it might even help to project the event and the profile of Melbourne as an architecture and design centre on to the world stage, one of the organisers’ stated ambitions. The commission, though, points to a critical misunderstanding of what has made the Serpentine Pavilion so successful as an architectural event, which is its experimental agenda.

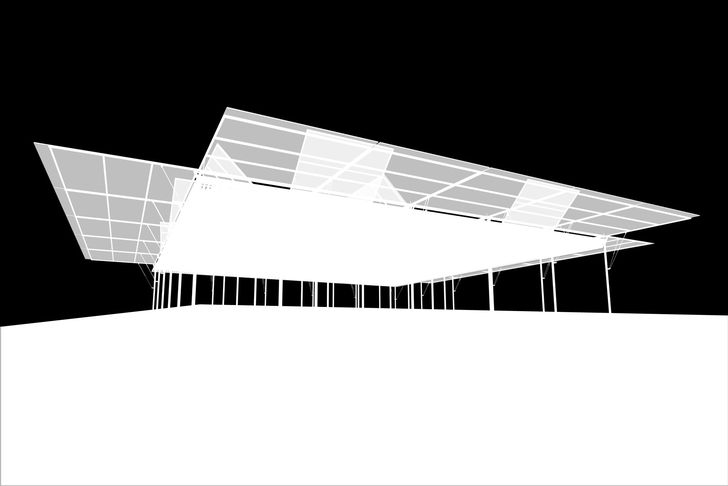

Sean Godsell’s design for the inaugural MPavilion is inspired by ‘outback sheds and verandahs.’

Image: Courtesy Sean Godsell Architects

In that regard, so far the MPavilion appears to be an opportunity missed. For one, there is the heavy focus on programming – the pavilion will serve as the vessel for what is shaping up to be 120 days of wall-to-wall architecture and design related events. Milgrom believes this will push the concept of the Serpentine further, but it could compromise it (as exciting as the prospect of such an events program may well be). It is the fact that the Serpentine Pavilion is largely un-programmed that allows it to be such a ready vessel for experimentation. Then, perhaps more troublingly, there is the requirement that the pavilion be demountable for re-assembly, to allow the City of Melbourne to plonk it, portacabin style, in another, as-yet-to-be-specified park. Finally though, Godsell qualifies as an old hand in architecture terms – his private residential design has been fetishized by publications all over the world, while the recent completion of the Design Hub on Swanston Street has given the Melbourne public ample opportunity to experience his architecture in the flesh.

Which raises the question as to how the process of commissioning has been managed. Milgrom described this to me as being almost like a curatorial commission, a judgement made by her foundation on the ‘architectural language of that person and how they express where they’re from.’ Given she is the chair of the foundation, the commission is less a ‘world-first public-private partnership’, as the organisers describe it, and more a case of arts patronage in a mould that would have been familiar to the Medicis – public architecture by fiat. If the MPavilion wants to live up to its self-drawn comparison to the Serpentine program, there is a strong argument that these decisions need to be more firmly divorced from the personal tastes and predilections of the patron.

By contrast, Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation in Sydney fosters innovation and emerging architectural talent through its annual pavilion Fugitive Structures. The 2014 installation, Trifolium, was designed by AR-MA.

Image: Jacob Ring

By way of example, we might look to the Sherman Contemporary Art Foundation’s annual pavilion in Sydney, Fugitive Structures. Also ‘inspired by’ the success of the Serpentine, Fugitive Structures is the result of an invitation-only competition, judged by a panel that includes not just the patron and their representatives, but architectural professionals and other independent advisors. This year’s pavilion, Trifolium, by emerging practice AR-MA, combines the crisply machined elegance of consumer electronics with an unsettling organicism, its formal components generated by algorithm and manufactured robotically, before being assembled on site by the architects themselves. The contrast with Godsell’s proposal for an agrarian steel box, where the primary innovation will be pneumatically operable walls, couldn’t be starker. This is 1960s regional modernism refracted through the mechanically dilating lens of Jean Nouvel’s 1987 Arab Institute, another iteration of Godsell’s well-established interests and precedents (most especially tropes present in his Carter/Tucker house).

Private money or not, a program such as this has the opportunity to leave a public legacy that is about more than plonk-itecture or the ephemera of events. Yes, Godsell’s pavilion, the first of four scheduled for the next few years, will almost certainly be refined and elegant, intriguing even. Let’s hope future pavilions, though, introduce Melbourne to fresher faces and more challenging, unfamiliar ideas.